Tabasco Sauce: Can it take the heat of global warming?

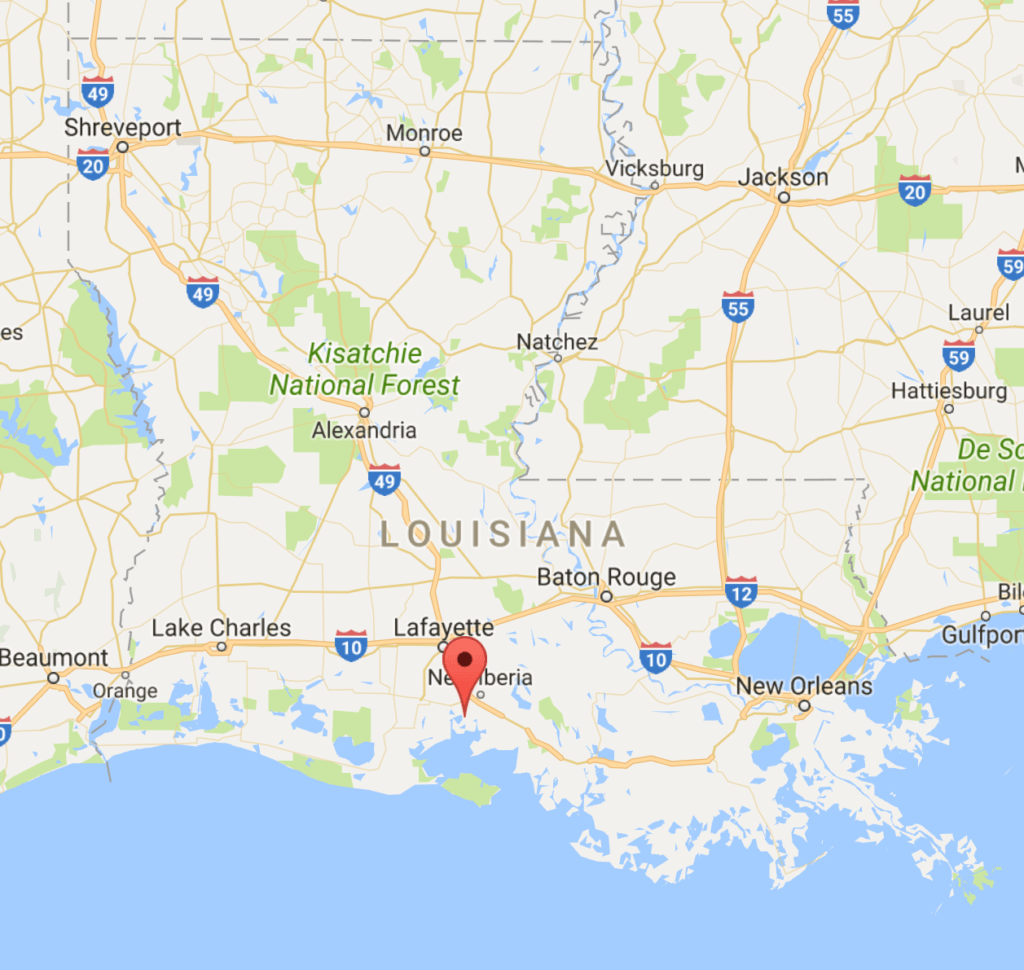

Every bottle of Tabasco sauce passes through Avery Island, Louisiana – an area susceptible to hurricanes and flooding.

For the past 149 years, oyster aficionados and hot wing lovers around the world have reached for an ubiquitous, red-capped glass bottle to add some heat to their dish. Tabasco hot sauce, introduced in 1868, has since proliferated to 165 countries and become the most well-known brand of hot sauce globally. What is less well-known is that every one of the 750,000 bottles of Tabasco produced daily originates in Avery Island, a small, marshy town located in the south of Louisiana. Here, five generations of the McIlhenny family have been cultivating Tabasco heritage for nearly a century and half. To ensure that the Tabasco legacy continues for generations to come, the McIlhennys must confront the effects of climate change on their tabasco chili supply chain.

The production of Tabasco hot sauce begins and ends in Avery Island, where tabasco chili seeds are cultivated, carefully selected, and then sent to fields in Latin America and Africa to grow into adult chilies. Once ripe, the chilies are mashed and shipped back to Avery Island to be aged in oak barrels for three years. This process provides the McIlhennys with control over the product quality, but exposes the supply chain to several climate change related risks.

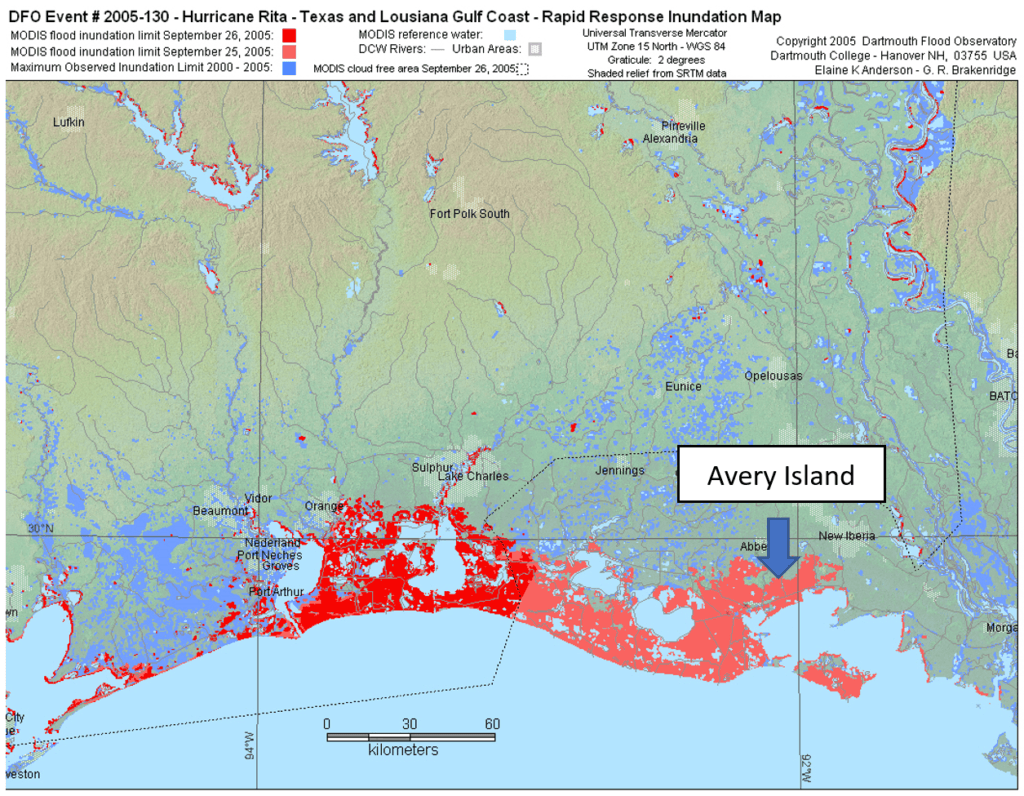

In the short term, the Tabasco seed bank and pepper fields in Avery Island must withstand increasingly frequent flooding and hurricanes resulting from climate change. In 2005, Hurricane Rita made landfall in Louisiana, causing storm surges and flooding that “at 9 feet 8 inches…was nearly double the highest flood level anyone could remember.”[1] Low-lying fields of tabasco peppers were flooded and the storage facilities holding as many as 53,000 barrels of inventory in-progress came within inches of being inundated. In response, the family invested $5M into constructing a 17-foot high levee and on-site backup generator to protect Avery Island and its fields from future flood events.

In the longer term, rising sea levels threaten the very existence of Avery Island. Avery Island is constantly fighting off saltwater intrusion, which kills marsh grass and leads to erosion of the wetland. According to the American Wetland Foundation, the coastal region is “vanishing at a rate of a football field every hour”. [3] The McIlhennys have been fighting against erosion by planting new grass, but with sea levels forecast to rise by half an inch a year[4], the tide will inevitably turn in favor of the ocean, and Avery Island along with much of the south coast of Louisiana will be submerged.

However, even this may not be enough to forestall the effects of climate change. As a single heritage plant (the McIlhennys have been growing the same tabasco seed for generations, stored securely in a vault in Avery Island)[6], the supply chain has a single point of failure in the form of the tabasco chili itself. A sudden freeze can kill a crop overnight, changes in lengths of growing seasons will introduce volatility into the chili supply, and unpredictable precipitation may result in poor growing conditions for the tabasco chili. And while geographic diversification mitigates some of these risks, in the Yucatán, Mexico, hurricane winds introduced African diseases to chili crops and resulted in “spotted and curled leaves and decreased plant yields”.[7] Research and development into seed variants that inoculate the crop against future agricultural risks would be a worthwhile endeavor for the company.

Beyond yield and crop viability, the McIlhennys must also grapple with increased variability in crop quality. This phenomenon, nicknamed “global weirding” [8], has resulted in unexpected colors and flavors in crops, in addition to reduced or unpredictably timed yields. An interesting question to answer would be how and if tabasco chili flavor or heat will vary under climate stress, and whether Tabasco is able to accommodate the increased variability in supply.

(Word count: 713)

[1] Kristina Shevory, “This Family’s Hot Stuff,” New York Times, March 30, 2007, [http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/30/business/31tabasco.web.html], accessed November 14, 2017.

[2] Elaine K. Anderson, “Rapid Response Inundation Map”, Dartmouth Flood Observatory, 2005, [http://www.dartmouth.edu/~floods/images/2005130GulfCoastRita.jpg], accessed November 14, 2017.

[3] Eileen Fleming, “Tabasco Joins Forces with America’s Wetland Foundation to Fight Coastal Erosion,” WWNO, April 12, 2012, [http://wwno.org/post/tabasco-joins-forces-americas-wetland-foundation-fight-coastal-erosion], accessed November 14, 2017.

[4] “Louisiana wetlands struggling with sea-level rise four times the global average”, March 14, 2017, [https://phys.org/news/2017-03-louisiana-wetlands-struggling-sea-level-global.html], accessed November 13, 2017.

[5] Mike Stones, “Swamp spice”, Food Manufacture, July 4, 2013, [https://www.foodmanufacture.co.uk/Article/2013/07/02/Tabasco-builds-global-food-business-on-three-ingredients], accessed November 14, 2017.

[6] Sanjay Gupta, “Tabasco: Fighting bland food since 1868”, CBS News, August 3, 2014, [https://www.cbsnews.com/news/tabasco-hot-sauce-industry-60-minutes], accessed November 15, 2017.

[7] Anne Raver, “Hot on the Trail of Chili Peppers”, New York Times, April 6, 2011, [http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/07/garden/07garden.html], accessed November 15, 2017.

[8] Gary Nabhan, “Global weirding and the scrambling of terroir”, Grist, October 28, 2010, [http://grist.org/article/food-2010-10-27-global-weirding-and-the-scrambling-of-terroir], accessed November 15, 2017.

While a Cholula fan myself, any macro factors that pose a threat to the supply of hot sauce are of serious concern to my gastronomic habits. As Tabasco seeks to diversify its chili cultivation, I believe the effect it has on its business has potential to be more impactful from a brand standpoint than a supply chain one. While Avery Island may be unique in its attributes for chilies, it can be reasonably expected that there many other geographies across the globe that will offer very similar, if not identical, conditions for growing chilies (Latin America and Africa, as mentioned). While the distinct flavor of Tabasco may remain with this supply chain change, the distinct brand perception of Tabasco may not. With so many hot sauce alternatives, how much of customer loyalty is felt to the family lore and heritage of the Tabasco brand vs the flavor of the sauce? If it’s important that the sauce be grown from Louisiana chilies by Louisiana families, Tabasco could find itself in a spicy situation, regardless of supply chain changes.

I wonder if the fact that chili can be preserved, and in this case, is required to age for three years before production, can be helpful for supply chain management. I imagine that the company can preserve surplus stock in a good year to build buffer inventory against bad weather. On the other hand, given such long production lead time, I expect it also poses challenges in terms of responding to market demand as there could be product shortage if the company under-forecasts demand (similar to the situation of aged liquor such as bourbon).

Another way to counter effects of climate change is to collaborate with a company like Indigo to produce more resilient or more consistent seeds.

Lastly, I wonder if the company can capitalize on “global weirding” by introducing seasonal or limited batches of products that celebrate variability in raw ingredients as opposed to trying to standardize all ingredients to produce a single line of products.

Similar to Boaty, I am not necessarily loyal to Tabasco but find the subject matter of your article fascinating. I find it particularly interesting that the seeds are sent elsewhere to grow into plants before returning to Louisiana for aging. I would think that the cost of transporting the crop is pretty expensive and generates significant greenhouse gas emissions. One thought I had was whether building indoor growing facilities or vertical farms for the chilis would allow for the family to control the product throughout the lifecycle and limit greenhouse gases. Southern Louisiana is an area of the United States that will continue to face significant challenges as a result of climate change and I suggest the family find an alternative location if they intend to keep the tradition going for generations to come.

It’s very interesting to me that the McIlhennys are effectively canaries in the climate change coal mine. They are already feeling the impacts of climate change in their supply chain through crop quality, volatile weather, and “global weirding,” and have taken steps to mitigate the issue by growing plants outside of Louisiana and planting new seagrass. Yet one of the key reasons the U.S. hasn’t taken stronger action against climate change is a lack of public urgency around the topic, including a large contingent that denies climate change altogether. It seems to me that consumer products, and food in particular, might be where the rubber hits the road in spurring consumers to care about climate change. Rising sea levels may feel abstract and long-term, but having to pay substantially more for Tabasco – or being unable to buy it, or having the flavor change substantially – feels very immediate. I wonder whether the McIlhennys have done any lobbying, advocacy work, or publicity around the issues they are facing. If they and other food companies behind popular and recognizable products speak out, it may help shift perception of climate change away from a long-term problem towards the present-day crisis that it is.

I completely agree with Richard Richardson that Tabasco will have the most control over its chilis if it pursues indoor growing facilities. A Jeff Bezos-backed startup called “Plenty” grows produce in 20-foot tall climate-controlled towers with LED lights and thousands of sensors and cameras to collect data, then used in a machine learning model to optimize the plants’ growth. Especially impressive is that plants grown in this technology can achieve 350x greater yield and use 1% of the water used in traditional farming. With a distinctive product like tabasco chilis, such control and optimization would be a big bonus and will allow them to iterate on improving the taste of their product. Given that this is where the future of the industry is headed anyway, I think it will be beneficial for Tabasco to pave the way.

Plenty: https://www.geekwire.com/2017/jeff-bezos-backed-indoor-farming-startup-plenty-opens-100k-square-foot-facility-seattle-region/

Tabasco is facing a clear challenge as Avery Island is experiencing more frequent devastating weather events like hurricanes. Even if Avery Island continues to be “above water” for a reasonable amount of time, Tabasco needs to evaluate the costs vs. benefits of continuing their seed sourcing and other operations in this location. I’m sure that after a major natural disaster event, there is considerable damage done to the operations on Avery Island and significant costs are incurred. At some point, Tabasco will need to bite the bullet and shift operations to a more reliable location that experiences fewer extreme weather events. Unfortunately, their $5M investment in a levee might not protect them for as long as they expect.

Additionally, as government dollars are used again and again to bail out homes and businesses that are in the path of extreme weather events like hurricanes, there may be incentives offered to Tabasco to move their operations. However, I understand that part of their legacy and brand is captured in their history on Avery Island, which would be hard to walk away from.