Submerged Subways: How Will the MTA Adapt to Rising Seas?

Using Hurricane Sandy as an analog for sea level rise caused by climate change, we explore the challenges facing the MTA.

Introduction

In a warming world, one of the most tangible impacts on the Earth will be rising oceans devouring land that was once dry, slowing shrinking the continents. It is likely that by 2100 sea levels will have risen by 2.6 – 6.6 feet due to a combination of melting ice caps and thermal expansion of warming ocean waters.[1] This puts coastal infrastructure at risk for flooding and inundation across all coastal countries. Many major cities throughout the globe are located on coastlines, with many billions of dollars of assets at risk in the US alone.[2] But, rather than try to grapple with scope and magnitude of this risk, I have chosen to focus on a specific yet representative entity as a case study into the effects of climate change: New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which is responsible for public transportation in the city. Unless steps are taken to mitigate the effects of sea level rise, devastating flooding, such as the flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 that resulted in $5 billion worth of damage[3], will impact the system with increasing frequency. This is most pertinent to the subterranean subway infrastructure.

How to understand the impact of sea-level rise

One of the most vulnerable inundation points in the city is at the seawall at Battery Park in Lower Manhattan, standing 5.74 feet above sea level. However, this does not mean that flooding will start occurring when sea level rises to 5.75 feet because sea level refers to mean sea level, which is the average of high and low tides. High tides at the Battery are 1.5 feet above mean sea level, thus water will start overtopping the seawall well before mean sea level exceeds the seawall height.[4] Additionally, hurricanes and coastal winter storms affect the New York City region periodically, creating storm surges that exceed typical high tides.

The costs

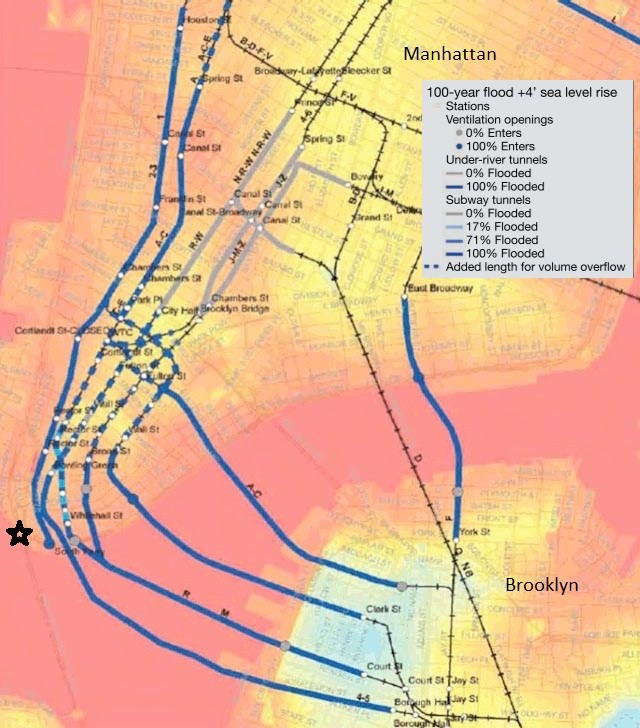

The MTA estimated that the cost of restoring service after Hurricane Sandy hit the city in 2012 was roughly $5 billion. Of that $5 billion, much of it was due to flooding that was caused when storm surge overtopped seawalls and inundated the low-lying areas in the city. For instance, the price tag associated with restoring South Ferry station, located on the southern tip of Manhattan next to Battery Park, was $600 million.[5] Station damage can be seen in Figure 1. The subway tracks are usually 20 feet below ground[6], allowing floodwaters to penetrate tunnels further inland than the surface flood waters. In a simulation of a storm surge similar to that of Hurricane Sandy, long stretches of Manhattan subway track become flooded in addition to the subway tunnels connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan (see Figure 2).

While Sandy was an anomalously powerful storm, as sea level rises, smaller and smaller storms will be able to create the same impact.

Figure 1: Submerged escalators at South Ferry Station.[7]

Figure 1: Submerged escalators at South Ferry Station.[7]

Figure 2: Map showing a simulation of subway flooding under storm surge levels similar to Hurricane Sandy. Battery Park is denoted with a black star.[8]

Figure 2: Map showing a simulation of subway flooding under storm surge levels similar to Hurricane Sandy. Battery Park is denoted with a black star.[8]

Mitigation

The extensive damage suffered by MTA infrastructure during Hurricane Sandy served as a warning about the impacts of sea level rise. In response to the storm, the MTA created the internal Recovery and Resiliency group to focus on the threat climate change poses to the MTA. This group has come up with both short-term and long-term plans for mitigating the impacts of sea level rise. The short-term plans focus on mitigation techniques such as sealing low-lying subway entry points with both inflatable and rigid barriers. Long-term plans have centered around permanent infrastructure such as the construction of seawalls to protect low-lying track and trainyards.[9],[10]

What’s missing

The mitigation strategy of the MTA is deficient since it does not own or control the fundamental points of vulnerability of its infrastructure, such as the seawall at Battery Park, which is owned by the City of New York.[11] Furthermore, there is a potentially flawed system of incentives in place, whereby local authorities are responsible for mitigation of impacts to climate change, yet the Federal Emergency Management Agency provides relief funds.[12] Having the Federal Government own the responsibility for flood relief and not own the responsibility for flood mitigation might not appropriately incent local authorities to take the necessary long-term actions needed to protect against sea level rise. Looking ahead to the year 2100 when sea level might be upwards of 6 feet higher than current levels, massive urban planning involving the MTA, city, state, and federal agencies must come together create a comprehensive adaptation plan to keep the subway and city afloat. However, the MTA will be tested by transient flooding events well before then.

Word Count: 783

[1] W.T. Peffer et al, “Kinematic Constraints on Glacier Contributions to 21st-Century Sea-Level Rise”, Science, September 2008.

[2] James J. McCarthy, Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the third assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

[3] Garath Johnson, “Breaking Down The MTA’s $5 Billion Hurricane Sandy Price Tag”, Nov. 28, 2012 http://gothamist.com/2012/11/28/breaking_down_the_mtas_5_billion_hu.php, accessed Nov. 4, 2016.

[4] Jeff Masters, “Hurricane Irene: New York City dodges a potential storm surge mega-disaster”, Nov. 30, 2011, https://www.wunderground.com/blog/JeffMasters/comment.html?entrynum=1995&tstamp=, accessed Nov. 4, 2016.

[5] Garath Johnson, “Breaking Down The MTA’s $5 Billion Hurricane Sandy Price Tag”, Nov. 28, 2012

[6] Cynthia Rosenzweig, “Responding to Climate Change in New York State”, 2011.

[7] Garath Johnson, “Breaking Down The MTA’s $5 Billion Hurricane Sandy Price Tag”, Nov. 28, 2012

[8] Cynthia Rosenzweig, “Responding to Climate Change in New York State”, 2011, file:///C:/Users/Jon/Downloads/ClimAID-synthesis-report.pdf, accessed Nov. 4, 2016.

[9] MTA, “2015 MTA Forum on Climate Adaptation, Resiliency, and Recovery Welcome Video”, June 6, 2015, https://youtu.be/sydeM8I5TNk, accessed Nov. 4, 2016.

[10] Alex Davies, “ONE YEAR LATER: Here’s How New York City’s Subways Have Improved Since Hurricane Sandy”, Ovt. 29, 2013, http://www.businessinsider.com/heres-how-nycs-subway-system-has-come-back-from-hurricane-sandy-2013-10, accessed Nov. 4 2016.

[11] https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/battery-park

[12] FEMA, “Signs of recovery: FEMA funding gives New York infrastructure a boost”, Jan. 20, 2015, https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4085/updates/signs-recovery-fema-funding-gives-new-york-infrastructure-boost, accessed Nov. 4, 2016

I agree that this is a scary concept. There are conflicting reports that suggest that flooding after Hurricane Sandy killed a significant number of rats [1][2], so at least there’s some silver lining?

Drastic action has to be taken. But the point that I would make isn’t so much about the policy as it is about who’s going to take care of it. You’d mentioned “massive urban planning involving the MTA, city, state, and federal agencies,” but I’d argue that given where New York City sits on the American political landscape, that sort of collaboration isn’t feasible.

New York holds a unique place in political discourse, and that’s evident just from this year’s political campaign. Both Clinton and Trump espouse strong anti-Wall Street rhetoric despite their own ties to the Big Apple. Ted Cruz took a lot of his for this “New York values” comment, but he said it for a reason and it clearly resonated with a lot of voters.

Those comments may be unfair or unjustified, but they don’t come from nowhere. With the exception of instances of true national tragedy — 9/11 being the obvious example — helping NYC doesn’t score you many political points. And it doesn’t help that it’s in a reliably blue state that shows no signs of becoming a swing state anytime soon. And as a result, I would expect help from the federal government.

I bring this up not to call out a technicality, but to recognize the pragmatic reality that NYC may not get the federal aid that it might need or want. So the city needs to consider options that it’s able to accomplish on its own, and that means finding cheaper and/or less aggressive but effective alternative.

I don’t know what that means. Does that entail building a Manhattan-wide version of Minneapolis’ Skyway [3]? Going with an elevated public transit system like you see in parts of Brooklyn or in Chicago? Returning to Robert Moses’ conception of the city, when he proposed fewer subways and more roads? I don’t know.

But unfortunately, it may have to be piecemeal, and it there may need to be some tough compromises.

————-

[1] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2225935/Hurricane-Sandy-probably-wiped-New-Yorks-rats-despite-warnings-rodent-apocalypse-say-experts.html

[2] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/07/nyregion/after-storm-rats-creep-inland.html

[3] http://www.skywaymyway.com/

Having lived downtown during Hurricane Sandy, I lived through the problem you wrote about. And, as you mentioned in your post, not much was done post-Sandy to prevent such flooding in the future. Right after Sandy, there was a lot of talk about putting a more robust seawall in place at Battery Park, but nothing has been built. Putting barriers in place to seal low-lying subway stations seems like a short-term cop-out. To make matters worse, I don’t believe much has been done to protect us from another catastrophic blackout similar to the Sandy blackout. The Con Ed power plant that blew up during Sandy is still right next to the East River. Sandy is not the last super-storm that New York City will have to endure, and sadly, I do not think that New York is any more prepared than it was 4 years ago.

Great post, JFW! Your post hits the nail on the head with respect to the hopelessness and short-sightedness of the political gridlock that is blocking significant progress on not only climate change mitigation initiatives, but infrastructure investment in general in the US, with NYC and the MTA as a metaphor for the whole planet. It also strikes a personal nerve for me, as someone who rode the MTA almost every day for the last three years, and whose neighborhood and subway train will bear the brunt of the nearly 200,000 displaced L-train riders, who will be forced to look for other transit options as the tunnel that the train runs in is closed for 18-months to repair residual damage from Sandy with the last of NY’s Sandy-related FEMA funds.

I disagree with EBS’s assertion above that federal and state governments are unwilling to help NYC because of its party-leanings, and see the lack of progress more as a result of the fact that no imminent risk exists (and FEMA funds will be there in that emergency case) and since governments are constantly making trade-offs between projects for which they never have enough funding, critical long-term improvement projects are frequently delayed until the last possible moment or crisis point. There are a couple different solutions that I would suggest further exploring:

– Whether NYC could raise additional funds for transportation projects through increasing tolls on existing bridges/tunnels or adding tolls on bridges in the city (e.g. all the East River bridges) that are not already tolled. This would place an increasing burden on car drivers to absorb some of the cost of the negative externality of climate change that they are contributing to by driving fossil-fuel powered cars.

– Whether private-public partnerships or an entirely private investment (enticed by tax incentives) could be used to drive faster progress on this issue. NYC has already begun to explore these options as solutions to its affordable housing crisis, by permitting rezoning for private real estate development projects that allot a certain percentage of their buildings to affordable or middle-class housing.

This is a great piece, JFW! Thanks for sharing.

As a native New Yorker, I have been a faithful MTA passenger for several years, including the darker post-Sandy days. Also stemming from global warming are increased instances of super-winter storms dumping several feet of snow for weeks and weeks in the city. Though the damage is typically not quite as devastatingly crippling as the damage from Sandy, with each storm the city subway system still suffers substantially with more instances of delays, mechanical issues, and interrupted service. This has a trickle-down effect as various professionals who work in the city and rely on the subway as their main form of transportation are forced to stay home, thus compromising business operations for a number of companies. Furthermore, the trains become more subject to wear and tear from increased exposure to icy rails, precipitation and moisture.

As we continue to experience more and more intense winter storms, sweeping, permanent changes need to be implemented sooner rather than later.