Shooting Oneself in the Foot(ball)

Can a small island produce the world’s best football (soccer) by itself? Will English professional football survive Brexit intact?

Winning Isn’t Everything

George Orwell, in a rare respite from his life’s work instilling dystopian anxiety in the hearts of schoolchildren everywhere, once said that “international football is the continuation of war by other means.[i]” Sadly for Mr. Orwell, his native England’s national team has been losing this war for a long, long time. Since their last (and only) World Cup championship in 1966, they have reliably disappointed in international play. Patriotic underachievement notwithstanding, the English have been successful in developing and exporting football’s number one commercial product, the Premier League (EPL). Rising isolationist sentiment on the island could threaten that success.

Global Heroes Supplying Success

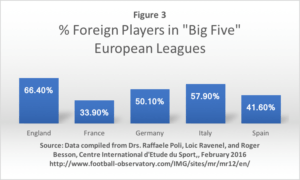

English football is governed by the Football Association (FA), whose primary mission is to foster the success of England’s national teams in international competition[ii]. The EPL is England’s top domestic professional league; its core product offerings are access to its matches, with most revenue stemming from TV deals[iii]. Despite years of middling outcomes in interleague play [Fig. 1], the EPL continues to dominate its competition in overall revenues [Fig. 2]. Why? Amongst other important factors, such as language and league structure[iv], is its position as the most diverse major football league [Fig. 3]. By featuring talent from around the world, the EPL captures the hearts (and dollars, won, and pesos) of the home country audiences that love them[v].

Obviously, players make up much of the value of the EPL’s product. Throughout their careers, footballers might be seen as raw materials, work in progress, and ultimately as a component of the finished goods – the matches themselves. Immigration policy, therefore, is synonymous with trade policy in this context, and has massive implications for the supply chain of talent for this major British export.

Unforced Turnover

While the particulars of the United Kingdom’s separation from the European Union are still being negotiated, last year’s Brexit vote will likely disrupt the EPL’s talent supply chain in three direct ways. First, it threatens to subject European players to British work visa rules designed to make it difficult to sign inexperienced foreigners[vi]. Second, it binds the EPL to the worldwide prohibition on international transfers of players under 18[vii]; the league had previously been able to source junior talent from within the EU. Thus, Brexit might grant the EPL’s top competitors a head start in signing promising young talent, and developing such talent is normally cheaper than purchasing the rights to an already established asset[viii][ix]. Finally, the devaluation of the pound, triggered by Brexit, has rendered already costly[x] international acquisitions even more expensive[xi].

In the short term, EPL leadership is actively lobbying the British government to establish more lenient visa policies for foreign footballers[xii]. It is too early to know how effective these efforts will be, but the EPL would be wise to move quickly from Brexit crisis management to more proactive talent supply chain planning.

The Future is African. And American. And Asian.

The EPL should be concerned with the possibility of further isolationist encroachments on their labor supply. Without the legal limits posed by EU membership, and given their incentives and constituencies, it is conceivable that both the FA and the British government move towards more restrictive labor policies[xiii][xiv]. Such policies would pose a serious threat to the league’s competitive position by disrupting the nature of its global supply chain.

America accounts for 24% of global GDP[xv]. Asia has the world’s fastest growing markets[xvi][xvii]; Africa has its fastest growing population[xviii]. All have relatively underdeveloped football infrastructures. While the EPL is currently aggressively pursuing customers in these markets[xix], it must also encourage its owners to see international investments as investments in their talent supply chain.

Specifically, the EPL should urge its teams to pursue multi-club ownership (MCO). By purchasing franchises in other countries’ domestic leagues, EPL clubs can identify and sign young, inexpensive talent locally[xx]. Once relevant parties (the FA, the government, and the team itself) deem a player old enough, skilled enough, and experienced enough to play in the EPL, the parent team avoids large transfer fees. Essentially, the MCO model encourages EPL teams to secure their supply chain by purchasing key suppliers[xxi]. Manchester City, with teams in America, Australia, Spain, and Uruguay, has been on the cutting edge of this strategy[xxii]. The EPL would do well to see others follow suit.

While a secure, cost effective international talent supply chain will benefit the EPL in any instance, other questions remain. What are the ethics of a talent supply chain such as this one? Is the Spanish league, with its homegrown players and interleague success, a threat to EPL’s commercial dominance?[xxiii] If so, should the EPL invest more in domestic player development?

Time—and talent—will tell.

(796 words)

————————–

[i] Chris Bond, “The power of football to unite,” Yorkshire Post, June 9, 2016, http://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/analysis/euro-2016-the-power-of-football-to-unite-1-7954454, accessed November 2017

[ii] The Football Association, “About,” http://www.thefa.com/about-football-association/what-we-do/strategy, accessed November 2017

[iii] Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu LLC, “Annual Review of Football Finance,” July 2017, p. 09, https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/sports-business-group/articles/annual-review-of-football-finance.html, accessed November 2017

[iv] Linda Yueh, “Exporting football. Why does the world love the English Premier League?,” BBC News, May 12, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/business-27369580, accessed November 2017

[v] “The English are bad at playing football—but brilliant at selling it,” September 2017, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21727929-english-clubs-are-being-trounced-their-european-rivals-yet-revenues-are-soaring-why-are-such, accessed November 2017

[vi] David Hellier, “Premier League Fights to Retain Playing Talent After Brexit,” Bloomberg, September 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-12/premier-league-fights-to-retain-playing-talent-after-brexit, accessed November 2017

[vii] “Premier league refuses to speculate on effects of UK’s Brexit from EU,” ESPN FC, June 24, 2016, http://www.espnfc.com/english-premier-league/story/2900990/premier-league-refuses-to-speculate-on-effects-of-uks-brexit-from-eu, accessed November 2017

[viii] Peter Cappelli, “Talent Management for the Twenty-first Century,” Harvard Business Review, March 2008, https://hbr.org/2008/03/talent-management-for-the-twenty-first-century, accessed November 2017

[ix] Nnamadi Madichie, “Management implications of foreign players in the English Premiership League football,” Management Decision, Vol. 47, Issue 1, (2009): 24-50, ABI/ProQuest, accessed November 2017

[x] Richard Burdekin and Michael Franklin, “Transfer Spending In the English Premier League: The Haves and The Have Nots,” National Institute Economic Review No. 232, May 2015. ABI/Proquest, accessed November 2017

[xi] Peter Berlin, “British football braces for life after Brexit,” Politico, May 10, 2017, https://www.politico.eu/article/british-football-braces-for-life-after-brexit-chelsea-ngolo-kante-english-premier-league/, accessed November 2017

[xii] Ben Rumsby, “Brexit: Premier League and FA at odds over immigration exemptions for foreign football stars,” The Daily Telegraph, April 6, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/football/2017/04/06/brexit-premier-league-fa-odds-immigration-exemptions-foreign/, accessed November 2017

[xiii] Richard Burdekin and Michael Franklin, “Transfer Spending In the English Premier League: The Haves and The Have Nots,” National Institute Economic Review No. 232, May 2015. ABI/Proquest, accessed November 2017

[xiv] David Schofield and Cristina Criddle, “Brexit wins: How will British sport be affected?,” The Daily Telegraph, June 24 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/2016/06/23/how-would-british-sport-be-affected-by-a-brexit/, accessed November 2017

[xv] Robbie Gramer, “Infographic: Here’s How the Global GDP is Divvied Up,” Foreign Policy, February 24, 2017, http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/02/24/infographic-heres-how-the-global-gdp-is-divvied-up/, accessed November 2017

[xvi] International Monetary Fund, “IMF Country Focus: Asia’s Dynamic Economies Continue to Lead Global Growth,” May 9, 2017, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/05/08/NA050917-Asia-Dynamic-Economies-Continue-to-Lead-Global-Growth, accessed November 2017

[xvii] The United States Trade Representative, “TPP Economic Benefits Fact Sheet,” https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Economic-Benefits-Fact-Sheet.pdf, accessed November 2017

[xviii] The United Nations, “Global Issues: Population,” http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/population/, accessed November 2017

[xix] “The English are bad at playing football—but brilliant at selling it,” September 2017, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21727929-english-clubs-are-being-trounced-their-european-rivals-yet-revenues-are-soaring-why-are-such, accessed November 2017

[xx] Steve Tongue, “Multi-ownership of clubs is way forward, says Duchatelet,” Reuters, February 20, 2014, http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-soccer-england-duchatelet/multi-ownership-of-clubs-is-way-forward-says-duchatelet-idUKBREA1J2AZ20140220, accessed November 2017

[xxi] Charlie Sammonds, “Inflated Transfer Fees Make Soccer’s Talent Supply Chain Paramount,” Innovation Enterprise, September 19, 2017, https://channels.theinnovationenterprise.com/articles/inflated-transfer-fees-make-soccer-s-talent-supply-chain-paramount, accessed November 2017

[xxii] Paul MacInnes, “Disneyfication of clubs like Manchester City keeps showing benefits,” The Guardian, August 31, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/football/2017/aug/31/disneyfication-clubs-manchester-city-red-bull, accessed November 2017

[xxiii] “The English are bad at playing football—but brilliant at selling it,” September 2017, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21727929-english-clubs-are-being-trounced-their-european-rivals-yet-revenues-are-soaring-why-are-such, accessed November 2017

While I agree that Brexit has had (and will continue to have) major implications for global businesses operating in the UK, I would challenge the notion that it will require the EPL to dramatically change course. Over the last 5 years, PL clubs have already altered their transfer strategy (or supply chain within the context of this discussion) to respond to certain regulatory changes within the game. Brexit is likely to only require incremental change rather than dramatic overhaul. I have listed some of these changes below.

1) Homegrown players rule: The FA, concerned by the England national team’s consistently subpar international performances, instituted a homegrown players quota for all PL teams. This meant that all squads had to have at least 8 (out of 25) squad spots for players who were on an English team for at least three years before the age of twenty-one. While these players could be foreigners who moved to England at a a young age (Cesc Fabregas of Chelsea FC is a good example), it was designed to provide more exposure to young English players. Greg Dyke, FA chairman had already indicated (pre-Brexit) he would like to further tighten this rule to restrict the influx of foreign players. It remains to be seen if this will have the desired impact on the England national team’s performances in major tournaments. Brexit shouldn’t change this significantly.

2) Financial fair play: A few years ago, UEFA tried to restrict flagrant overspending by clubs in Europe’s top leagues by instituting Financial Fair Play restrictions. While some clubs seem to blatantly disregard the rules, others (like Manchester City) have started buying satellite clubs in international markets to source talent. However, rather than using these clubs to source local talent, clubs tend to used them to hoard ‘excess player inventory’ through player loans which they can later tap into at below market rates. Using the foreign clubs to source local talent is still likely to run into labour restrictions when the Australian or American players want to play in Europe.

To conclude, while I agree the EPL would benefit from a single EU market, Premier League clubs have proven themselves to be shrewd operators in a changing financial and political landscape.

Well researched article Yohannes – very informative! Let us assume absolute best case: implying EU governments provide European players with British work visas, UK can still source international player transfers (under the age of 18 years old) from the EU, and limited devaluation of the pound currency triggered by the Brexit. Even under these best-case circumstances, one could argue that UK/EU/abroad football teams, fans, and sports consumers will be less likely to support United Kingdom’s football sport because of the post-Brexit political and social tensions and negative consumer perceptions that have arisen. My point being is the UK will have an uphill battle in desirability to convince fans, players, and teams to respect each other despite the strained relationship globally (regardless of the three above issues mentioned), which will only compound with further challenges.

To pivot the conversation, you mentioned the desired growth of exporting football to America, Asia, and Africa economies. Do you think the boldly-present isolationism and populism movement within the United States for instance, also reduces the success of the football sports expansion? Are American’s simply less likely to embrace the unknown and resist the introduction of football as a primetime USA sport, instead, relying on their tried-and-true American football and NASCAR obsessions? It’s an interesting debate to consider, the role of sports as a venue to bring together or divide groups of people across the world. One must ask: how can sports better unite across borders? Are the Olympics successful at achieving a unifying spirit while promoting healthy competition across nations, what can be learned and applied to football?

Football (or should I say soccer?) is a business where the strongest always prevail in the long run. It is therefore not surprising to see a strong correlation between team budget and performance. As a result, the EPL will stay at the top as long as it remains the richest league. Today the EPL generates the highest revenue (c.€5bn), well ahead of Germany and Spain (c.€3bn) because it has great appeal to foreign markets [1]. This current popularity creates a huge fan base overseas that will remain loyal to the EPL in the years to come, as demonstrated by Liverpool fans’ motto “Once a Red, always a Red!”. I believe that the EPL has created so much fan stickiness around the world that it will be difficult to displace it.

I also want to challenge your point on the success of the EPL being due to the diversity of its league. Based on figure 2 and 3, the Italian league is the second most diverse league and yet it only ranks fourth in terms of revenue generation. As a result, diversity in volume does not lead to more appeal but I believe that having the best players (whether local or foreign), even in a limited number, is the key driver to league popularity. And as we all know, best players are mostly acquired at a late age from second-tier teams and are seldom developed in-house. Consequently I believe that due to its purchasing power, the EPL will keep buying top players and maintain the virtuous circle that has allowed it to become the most popular football league.

1. https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21727929-english-clubs-are-being-trounced-their-european-rivals-yet-revenues-are-soaring-why-are-such

A refreshing take on Brexit and its implications! Thanks, Yohannes. It’s interesting that you raise both the Football Association (FA) and the EPL as I think both of these parties have conflicting interests when it comes to Brexit. The Premier League runs separately from the FA and represents the interests of the 20 clubs participating in the league. The FA, as you note, is tasked with running English football outside of the leagues, including the national team and the grass roots playing of the game. The FA has long been concerned about the waning development of young English talent and that a successful, lucrative Premier League stifles the development of the English National Team. One of your sources (xii) references that the FA has gone as far as to consider lobbying the government to prohibit the movement of European players to the UK, which is in direct opposition to the lobbying that the Premier League is doing. The downside of a restricted labor market is access to global talent yet and potentially access to a global fan base, yet I do believe there may be longer term benefits to the league by having to nurture more English talent at home. Selfishly, this may improve the performance of the national team, as Premier League clubs devoting millions into local player development in lieu of exorbitant transfer fees may lead to global talent being manufactured at home. Some of the most popular and lucrative teams in the premier league in the last decades have had a core backbone of English players (the famous Manchester United Class of ’97, Chelsea’s title winning teams under Mourinho), which speaks to their global appeal and hints that the strength of the league may carry on despite less international representation. All in, there’s a good chance that in the mid-longer term, development of English players may not hamper the league as much as we think.

Apologies for the length, but your MCO point and Ninad’s reference to Financial Fair Play has hit a nerve. MCO’s are certainly an exploitation of the system and as a fan, I have concerns about the way that clubs are now buying up other clubs in other leagues around the world as it leads to enormous conflicts of interests in developing players and sustaining a club. It also saps my own passion for supporting a local club, often steeped in tradition. An advantage of Brexit may be that it aids Financial Fair Play by making the MCO model less tenable and more difficult to operate as transferring players from the ‘spoke’ clubs to the ‘hub’ club becomes harder.

Really interesting topic! As a lapsed fan of Manchester City, I hope the effects of Brexit on the EPL are limited in nature.

I especially liked your take on strategies to broaden the talent pipeline. Still, as more teams in the EPL look abroad to develop and transfer talent, they should beware that newer football markets are looking to develop, retain, or acquire their own talent. China is investing heavily in national football development programs for children and Chinese teams are paying top yuan for foreign players [1]. Likewise, as football grows in popularity in the US, the MLS looks to grow its number of teams and share of national attention [2]. U.S. teams are increasing rapidly in value, from an average of $37M in 2008 to $185M in 2016, which is a strong signal that their spending power is increasing as well [3].

Without knowing the specifics of the U.K. foreign visa process, developed countries generally require countries to prove that similar talent could not have been found otherwise domestically before approving a foreign visa (a process commonly referred to as a labor market check). It seems English football teams will be able to easily navigate a labor market check, but I would agree that there may still be a significant impact on compensation and benefits, due to financial complexities resulting from Brexit. Teams will either not be able to offer the same compensation level to an individual player, or their player budget will not go as far.

My other concern is that access to the EPL—in terms of game attendance of foreign fans (i.e. becoming more costly/difficult to travel to the U.K. for games) and broadcasting rights—may be at risk to some extent.

1. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/04/world/asia/china-soccer-xi-jinping.html

2. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/08/sports/soccer/mls-expansion-nashville-cincinnati.html

3. https://www.forbes.com/sites/markjburns/2016/10/26/mls-records-banner-year-in-2016-cements-position-among-top-u-s-pro-sports-leagues/#3239be6478a2

Thanks, Yohannes, for a very interesting article on a topic that’s worrying to me as a big EPL and Manchester United fan (part of the classic Asian audience which generates all that money for the EPL). I think you’re absolutely right that Brexit restrictions, if imposed by the UK government, will be a significant issue for prospects of attracting the best players to the EPL. The effect will be compounded by Grant’s point – as the pound weakens, UK clubs will have to play significantly more in both transfer fees and wages to be able to offer the same compensation to players as they would obtain in Spain or Germany. In today’s scenario, when UK teams are doing poorly in the European interleague play and given the attraction of South American and African players to historically aspiration and sunny Spain, it seems difficult that the best players would want to come to the UK. But I’m not convinced that multi-club ownership is the answer – the factors I’ve mentioned would persist even then, and the assumed player ‘loyalty’ due to MCO is likely an unattainable dream in the professional sports world.

However, the question remains of whether obtaining the best players is the reason for the EPL’s success. Only 5 of the world’s 24 best players, shortlisted by FIFA (football’s world governing body) for the 2017 best footballer awards, currently play in England (and none in the top 5), compared to a staggering 11 in Spain – Germany, Italy and France follow close behind with 3 each [1]. The EPL’s team have fared miserably in inter-league play, showing up its claims of being the best league by footballing quality. I believe it’s more likely that the popularity of the EPL is due to other factors like more sophisticated marketing, first mover advantage in the emerging footballing markets of Asia and Africa and an aggressive, ‘blood and thunder’ all-action style of play. Perhaps the biggest hope of the EPL is the fact that they can continue surviving without the very best players, if they continue to do the other things well.

[1] http://www.fifa.com/the-best-fifa-football-awards/news/y=2017/m=9/news=fifa-fifpro-world11-2017-shortlist-revealed-2908322.html

Thank you- what an interesting application of TOM. I am fascinated by your take on Brexit’s potential disruption of the supply chain for the English Premier League and the global football landscape. Pursuing a multi-club ownership strategy seems reasonable from a talent development standpoint, my concern is that this might result in a mismatch in the identity of the players with club fans. Building on Fritz’ response above, ultimately, the most important thing for key stakeholders within the English Premier League, other than winning, is engagement with the fans. From what I understand, the strength of the Spanish league is its ability to use star players to tap into Spain’s intense regional pride during competition. Would sourcing and developing talent using the MCO model dilute the ties between the player and/or club and the fans?

Thanks Yohannes – nicely researched and argued. You raise an interesting question about the ethics of the MCO model, in spite of the more straightforward economic benefits to the team. While I agree that it makes economic sense for EPL clubs to acquire players through the purchase of other countries’ domestic clubs and later transferring the best ones into the EPL, the players are the big losers under league design. By tying up talent at a really young age, no player would have the chance to pursue their market potential and earn their fair value in wages, particularly as rising stars began to differentiate themselves in the domestic leagues. Ultimately, that’s not a fair outcome for the players who rightfully deserve the opportunity to accumulate incremental wealth as their talent and demand grow. And as Fritz pointed out, it also raises conflicts of interest in terms of how the rosters are managed between the EPL club and the other teams in the MCO, with the fans of those other teams also ultimately losing out as the best players are constantly migrated upwards to the premier league.

Thank you Yohannes, it was a really interesting article in many ways. What struck me most, as someone who admittedly doesn’t follow football, was how a team that does not dominate in winning is still able to dominate in revenue. In your article you discussed how this is largely due to the international composition of the teams, drawing ardent fans from around the world. However, in several comments people raised good points about how other teams who are largely international do not draw this same level of success. Though many factors are ultimately important, we can agree that there is something about the EPL brand that creates a passionate fan base, or a high level of stickiness in consumers.

Darrin commented with concern about the EPL’s ability to “convince fans, players, and teams to respect each other despite the strained relationship globally.” Initially I agreed with this statement thinking that national pride played a significant role in sporting. However, with isolationism sweeping many countries beyond just the UK, it seems as though people may want to keep their sports and their politics separate. While the EPL for many consumers is a source of pride for England, for many international fans it is simply their favorite football team. While isolationism’s strains are strongly felt in many ways, I think that EPL stands a great chance of standing on the sidelines of this debate and letting football be great for football’s sake.