Replicating MPESA: Lessons from Vodafone(Safaricom) on why Mobile Money fails to gain traction in other markets

The success of MPESA, Kenya’s premier online mobile money transfer and financing system has proven very difficult to replicate in other emerging markets. In Kenya, MPESA has been wildly successful. Launched in 2007, MPESA allows users to send money to each other using basic SMS technology. It currently has 24 million registered users (95% of adults), and total transaction value of Kshs 5.29tn ($~50bn)[i] equivalent to 75% of the $65bn GDP flowing through the system[ii].

Despite its success and clear benefits to the economy, MPESA has proven incredibly difficult to replicate in other emerging markets, even in neighboring countries[iii], and even by MPESA’s parent company Vodafone (Safaricom) in other markets that it operates in [iv]. Understanding the evolution of MPESA’s business model and its operational decisions can shed light on winning strategies and challenges in replicating the model.

Business model

MPESA’s original concept was simple: it would allow users in Kenya’s major cities to send money to relatives in rural areas. There was a ready demand for the service and no alternatives. As the subscriber base grew, MPESA’s product offering expanded, and users are now able to pay bills, buy groceries, withdraw from third-party ATMs, pay for government services, receive social protection payments[v] . It creates value to users by reducing transaction costs and cutting lead times to ~zero, and captures the value by charging transaction charges of 0%-2% to the receiving party of the transaction. In 2016, MPESA’s net revenues hit $302.5 million[vi].

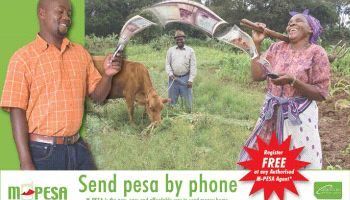

Figure 1: Illustration of MPESA’s original ecosystem[vii]

Operational Model, Levers and Decisions

MPESA tapped into a large, untapped demand for domestic remittances by providing a simple money transfer service that was accessible to any type of mobile phone. Safaricom, MPESA’s parent company, bolstered awareness by heavily promotingit with a clear proposition – “send money home”, targeting city-dwellers who wanted to send money to rural areas iii. Educating the end user about an intuitive product using simple messaging was key to driving adoption [viii].

MPESA relied heavily on scale and network effects by leveraging the the relatively high level of mobile penetration in Kenya [x]; [xi] and the monopolistic nature Safaricom which commanded 70% of mobile phone users in 2007[ix]. Safaricom understood the value of middlemen, so rather than vertically integrating and deploying its own distribution network, it relies on a network of 100,000+ independent agents (i) and third-party ATMs to handle deposits and withdrawals. The agents provide geographical flexibility, enhanced information flow, end-user liquidity and security verification while significantly reducing setup costs. To align incentives across the channels, Safaricom provides generous commissions to agents and third-parties vi, though this creates some transactional friction in the system.

Safaricom also benefited from a favorable regulatory framework that allowed telco operators to handle financial transactions. In part, this was because it was 60% government owned viii. It also gained regulatory and political support in because MPESA was not launched with a profit incentive (there was no real profitable precedent globally), but rather as a CSR project to boost Safaricom’s brand image while solving an obvious need in society[xii]. Safaricom also complied with legal restrictions that limited transaction sizes to ~$700 a day [xiii] to prevent/reduce money-laundering, corruption and financial liability.

To respond to an ever-changing competitive landscape, Safaricom has improved its product offering significantly over the years, despite a lot of internal resistance to innovate. The closed-loop nature of the software, initially designed to enhance security, made it difficult/impossible to integrate with third-parties until September 2015 [xiv]. Since then it has enabled API integration that allows third party fintech applications to access its system. This has led to a proliferation of the suite of products, including: global money transfers, bitcoin exchanges, POS enablement, ATM integration, etc. Currently, Safaricom supports more than 43,000 merchants in Kenya alone (i) though there are still significant limitations on the integration capabilities [xv].

The Road Ahead for MPESA and Mobile Money

Figure 2: Key enablers driving the delivery of mobile money [xvi]

MPESA replicas in Latin America [xvii], India [xviii], South Africa [xix], and most other emerging markets have either outright failed or lacked traction. MPESA succeeded because it benefited from network effects of scale and near-monopoly status; first-mover advantage; lack of viable alternatives; a favorable regulatory environment and a large nascent demand for the service. It also made operational choices such as heavy marketing; incentive alignment with channel stakeholders; and technology enhancements. Other mobile money solutions fail because they’re unable to exercise some of these levers.

Locally, the success of MPESA has reduced barriers to entry for third parties, particularly as it has already established a national network of agents and third party interfaces. Switching costs are increasing lower, and multihoming – by both end users and agents – will reduce the stickiness of subscribers. Additionally, the scale of MPESA has increased regulatory scrutiny. As such, MPESA will need to enhance technology and align stakeholder incentives even more to respond to changes in the competitive landscape.

[799 words]

[i] http://www.safaricom.co.ke/images/Downloads/Resources_Downloads/Safaricom_Limited_2016_Annual_Report.pdf

[ii] http://data.worldbank.org/country/kenya

[iv] http://qz.com/467887/why-south-africas-largest-mobile-network-vodacom-failed-to-grow-mpesa/

[v] http://fsdkenya.org/an-overview-of-m-pesa/

[vi][vi] BBVA Research: MPESA – The Best of Borth Worlds. Jul 02 2014. Accessed 11/18/2016

[vii] Mobile Payments in Emerging Markets Issue No. 04 – July-Aug. (2012 vol. 14) ISSN: 1520-9202 pp: 9-13 DOI: http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/MITP.2012.82 Accessed on 11/18/16

[viii] http://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/case-study/case-study-vodafone-mpesa-mobile-cash-transfer-service-future/story/211926.html

[ix] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2007-08-27/safaricom-on-a-tear-in-africabusinessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice

[x] Jenny C. Aker and Isaac M. Mbiti. Mobile Phones and Economic Development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 3—Summer 2010—Pages 207–232

[xi] https://energypedia.info/wiki/Mobile_Phone_Market_in_Kenya

[xii] http://centres.insead.edu/social-innovation/what-we-do/documents/INSEADSocialInnovationCentre5693-Vodafone_MPESA-CS-EN-0-09-2014-w.pdf

[xiii] Daily Nation. Safaricom in talks to raise M-Pesa limit. Monday, October 4 2010. Accessed 11/18/16

[xiv] Finance Magnets. M-Pesa Opens Up to 3rd Party Developers in Kenya as Safaricom Launches API

[xv] http://www.financemagnates.com/fintech/payments/m-pesa-opens-up-tp-3rd-party-developers-in-kenya-as-safaricom-launches-api/

[xvi] Ernst & Young. Mobile Money: An overview for global telecommunications operators

[xvii] CGAP: The Replication Limits of M-Pesa in Latin America. 20 July 2016

[xviii] http://qz.com/222964/why-mobile-money-has-failed-to-take-off-in-india/

[xix] Reuters. MTN scraps mobile money business in South Africa. Thu Sep 15, 2016.

Great article, David! I wrote my post on M-Pesa as well, but specifically on its impact on Kenya and Safaricom. I thought that your perspective on why the service is failing to pick up in other countries was very interesting.

I agree with you that the next biggest thing for Safaricom in Kenya is for it to open up its APIs for third-party developer integration, and the company has taken the right first steps in doing so. I’d argue that the company needs to be much more aggressive in this. There still seems to be some concerns about how seamless the integration process really is for developers, and that’s preventing some developers from working with M-Pesa. [1] It’ll be interesting to see how this all plays out.

I like your list of the reasons why M-Pesa (and similar mobile payment services) are failing to gain traction in other markets, and I think the interesting thing is that you need to assess the reasons on a country-by-country basis. I don’t think that Vodafone can necessarily replicate the success of Safaricom by using the same playbook as in Kenya, and I’d argue that at a high level this is probably the biggest reasons for its failure. For example, at M-Pesa’s launch in South Africa, roughly ~70% of the populations already had bank accounts, and a lot of alternative mobile payment services already existed. [2] First of all, I’m not sure it even made sense for Vodafone to launch M-Pesa in this type of environment, but even if it were to do so it should’ve focused more on setting up a broader infrastructure of retail agents. At launch, there were only 6,000 agents in South Africa; given that the financial institutions were more mature in this market, I think that Vodafone needed a broader reach to create real value for users. Across countries, especially in areas with more developed financial institutions, working with regulators will also be very important. I agree with you that Safaricom faced extremely favorable (and unique) regulatory conditions in Kenya.

[1] https://www.cgap.org/blog/just-how-open-safaricom%E2%80%99s-open-api

[2] http://qz.com/467887/why-south-africas-largest-mobile-network-vodacom-failed-to-grow-mpesa/

Thanks for the post, David! I am impressed with the roll out of M-Pesa and its success in Kenya. I honestly think the US mobile payment/ transfer industry can learn a thing or two from this. To Kevin’s point, I agree that Vodafone cannot just take this playbook and implement in other emerging markets – rather they should assess the different nuances on a country by country basis – i.e. infrastructure, existing competition – to determine how best to enter the market.

Vodafone actually rolled out M-Pesa in Ghana (called Vodafone cash) and it has been fairly successful. I am interested in the relationships between the different mobile network providers in these countries. You mentioned that Safaricom benefits from scale and network effect in Kenya and I imagine M-Pesa only works for customers who are subscribed to Vodafone. In Ghana however, Vodafone is the second largest mobile network provided (MTN is the largest with double the subscriber base and also has Mobile money). Do you know if Vodafone is planning to interconnect M-Pesa with other mobile money services from competitors, especially in countries like Ghana where it hasn’t monopolized the market?

I think it’s worth highlighting that, per your reference xii, the project got off the ground as a result of a grant from the UK’s DFID for 50% of the initial capital outlays. This is a great example of a government agency looking beyond its shores to support forward-thinking projects in developing countries whose future will directly impact its own. Whether altruistic or self-serving, successful efforts such as MPESA demonstrate the viability of Public/Private partnering on projects that align with the goals of both parties. It also serves as a counterpoint to the push for privatization of industries. When a government uses its reach and control for positive ends, such projects have a strong chance of success.

Great read David! To the points of why it worked in Kenya and not elsewhere, I’d definitely concur with the lack of an alternative and large nascent demand for the service. It’s notable that credit cards and bank accounts were (and still are) not widespread, which definitely negatively impacts this service. I wonder what happens to M-PESA in the long run though, once the country develops and those both become more widespread. The commissions charged throughout the system alone give me some cause for concern once the nation’s financial system does develop more.