Moving the World: How climate change can allow Maersk to dominate the future of transport

Climate change will impose substantial new costs on transportation and logistics industries. Yet is it all bad for the maritime sector, and Maersk, its largest constituent?

The shipping industry, accounting for over 3% of global CO2 emissions and physically touching every corner of globe, is all but guaranteed to be significantly impacted by climate change and associated regulatory reforms[i]. This will affect few organizations within the industry more profoundly than Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping company, responsible for transporting 15% of global seaborne freight[ii]. Yet while a changing climate presents both opportunities and costs, addressing the challenge well could provide the company with a virtually unassailable competitive advantage.

The most visible benefit for shipping lines is the emergence of the Arctic Northeast Passage, traversing north of Russia. The existing route between Europe and Asia is already the world’s second busiest sea route, and passes near a number of piracy-laden spots including around the Malacca Strait, Somalia, and the Suez Canal[iii]. The new route has the potential to shave roughly two weeks off of the standard Asia-Europe container shipping route, reducing a 35-day voyage down to roughly 21 days[iv]. However, the route has not melted sufficiently yet, with it only usable a few months a year during the summer – “the way global warming is going, of course there is the opportunity…but it will definitely not be within the next 15 to 20 years” according to Nils Andersen, former Maersk CEO[v]. Continued warming however could, by 2040, significantly shorten the length of Asian-European supply chains.

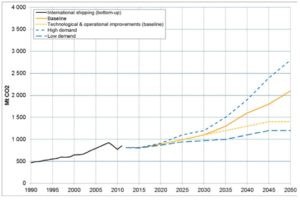

Meanwhile, Maersk and the shipping industry face certain challenges they will need to adapt to as regulatory bodies, primarily the International Maritime Organization (IMO), begin the process of mandating tougher environmental standards. Two primary regulatory changes are in process – forced reduction in CO2 emissions, and a reduction in sulfur content in fuel. The maritime shipping industry already accounts for roughly 3% of global CO2 emissions, and the IMO forecasts that this will rise by between 50-250% by 2050[vi]. Shipping could thus account for 17% of overall global emissions, if no change occurs[vii]. Related to more stringent reductions in CO2 emissions, the IMO is also in the process of mandating that sulfur content in fuel be reduced to 0.5% by 2020, which could as much as double fuel costs[viii]. While it varies by carrier, fuel currently represents roughly 40% of overall container line operating costs[ix].

Figure 1: Existing and Projected Maritime CO2 Emissions

Maersk has begun to address the climate change challenge and these impending regulatory changes in two ways: voluntary leadership on key climate impact reduction goals, and industry leadership to force more drastic changes. On an individual front, the organization has committed itself to reducing total CO2 emissions by 30% by 2020, from its 2010 baseline, and a 60% reduction in emissions per container by 2020, from a 2007 baseline[xi]. It plans to achieve these gains through slowing down average vessel sailing speed, retrofitting vessels with new environmentally-friendly technologies, and switching to cleaner fuels in select ports[xii]. To date changes have reduced Maersk’s emissions-per-container levels to roughly 20% below the industry average[xiii]. Further changes are going to increase costs for Maersk, though it maintains it is willing to invest provided that the rest of the industry does so as well. On this front, it has thus begun publically and privately pushing the IMO and other key stakeholders to strengthen regulations governing the maritime industry.

Going forward, much of the gains for shipping and the maritime industry will likely come from even greater efficiency gains on larger vessels, but also improving the overall efficiency of multimodal supply chains. This will primarily consist of improved data exchange and system design between freight forwarders, on-shore logistics firms, port, and shipping lines. Maersk’s continued investment in APM Terminals, the port management firm owned by the company, and its industry leadership in data and analytics, indicate that it fully understands this situation. The challenge for the firm will be to continue investing in these solutions despite a severe downturn in shipping line profitability – a climate that has already forced either the bankruptcy, merger, or acquisition of 10 of the world’s largest shipping lines in the past year and will see the industry lose $10 billion this year on $170 billion in total revenue[xiv][xv].

Climate change and a changing regulatory environment are poised to have a dramatic impact on Maersk and the wider shipping industry’s operations for decades to come. Should Maersk maintain its leadership position in the industry around climate issues, it will likely become the industry leader with a virtually unassailable competitive advantage. (751 words)

[i] Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department Economic and Scientific Policy A, “Emission Reduction Targets for International Aviation and Shipping,” European Parliament, 2015, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/569964/IPOL_STU(2015)569964_EN.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[ii] Richard Milne, “Arctic shipping routes still a long-term proposition, says Maersk,” The Financial Times, October 6, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/f44bd53a-2e74-11e3-be22-00144feab7de, accessed November 2016.

[iii] Data on shipping routes excerpted from The World Shipping Council, 2013, http://www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/global-trade/trade-routes, accessed November 2016.

[iv] Tom Mitchell, “First Chinese cargo ship nears end of Northeast Passage transit,” The Financial Times, September 6, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/010fa1bc-16cd-11e3-9ec2-00144feabdc0, accessed November 2016.

[v] Richard Milne, “Arctic shipping routes still a long-term proposition, says Maersk,” The Financial Times, October 6, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/f44bd53a-2e74-11e3-be22-00144feab7de, accessed November 2016.

[vi] Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department Economic and Scientific Policy A, “Emission Reduction Targets for International Aviation and Shipping,” European Parliament, 2015, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/569964/IPOL_STU(2015)569964_EN.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[vii] John Vidal, “Shipping ‘progressives’ call for industry carbon emissions cuts,”, The Guardian, October 19, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/oct/19/shipping-progressives-call-for-industry-carbon-emission-cuts, accessed November 2016.

[viii] Justin Braden, “IMO sulfur caps set to raise shipping fuel surcharges,” JOC, October 27, 2016, http://www.joc.com/regulation-policy/transportation-regulations/international-transportation-regulations/imo-sulfur-cap-set-raise-shipping-fuel-surcharges_20161027.html, accessed November 2016.

[ix] Justin Braden, “IMO sulfur caps set to raise shipping fuel surcharges,” JOC, October 27, 2016, http://www.joc.com/regulation-policy/transportation-regulations/international-transportation-regulations/imo-sulfur-cap-set-raise-shipping-fuel-surcharges_20161027.html, accessed November 2016.

[x] Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department Economic and Scientific Policy A, “Emission Reduction Targets for International Aviation and Shipping,” European Parliament, 2015, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/569964/IPOL_STU(2015)569964_EN.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[xi] AP Moller – Maersk, Sustainability Report 2015, p. 9, accessed November 2016.

[xii] Jacob Sterling, “Maersk Line and the Environment,” downloaded from EcoCouncil / Maersk, www.ecocouncil.dk/documents/praesentationer/717-101129-skibsfart-js/file, accessed November 2016.

[xiii] AP Moller – Maersk, Sustainability Report 2015, p. 9, accessed November 2016.

[xiv] Leo Lewis, “NYK, MOL, and K Line to combine container shipping units,” The Financial Times, October 31, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/dbdf7318-9f5e-11e6-86d5-4e36b35c3550, accessed November 2016.

[xv] “Profits overboard,” The Economist, September 10, 2016, http://www.economist.com/news/business/21706556-shipping-business-crisis-industry-leader-not-exempt-profits-overboard, accessed November 2016.

Good post! It sounds like this is mostly a corporate responsibility / pubic relations move for Maersk? I don’t see the competitive advantage for them. Seems like if Maersk and the other shipping companies all try to hit these CO2 targets in a coordinated way, basically all they are doing is pushing the cost required off to customers (they can’t, after-all, opt to become even less profitable). I guess the only way I can think of that this gives Maersk a competitive advantage is if other companies can’t hit the targets for some reason and are penalized in some fashion.

Given that Maersk and other shipping companies control so much of the worlds flow of goods and products, any regulation on this sector can have rippling effects. Could international regulation that taxes for carbon intensive products and subsidizes carbon friendly products be a viable solution. I know you mention that the “maritime shipping industry already accounts for roughly 3% of global CO2 emissions”. But shouldn’t we also take into account the CO2 emissions that were resulted from the production of the goods the shipping industry ships?

Thanks for the interesting read. I hadn’t appreciated climate change is literally heating up global trade via the Artic Northeast Passage – are there additional passages expected to shorten shipping routes and enable faster, cheaper journey in other parts of the world? What regulatory requirements or incentives should be implemented to accelerate appropriate measures, most likely at the expense of corporate profitability (i.e. retrofitting vessels, switching to cleaner fuels or slowing by vessel speed directly hits the bottom line today, vs. waiting 20-25 years to replace retiring vessels with more eco-friendly ones), especially in the difficult macro environment? Based on my research, the EU’s first step in GHG emission reduction is requiring large ships using EU ports to report verified emissions, beginning in 2018 (https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport/shipping/index_en.htm). Is this sufficient – or urgent – enough?

Great article Adam! It seems to me that given the relatively small number of major players that dominate the global shipping industry, it would make sense to coordinate efforts in order to “help” draft new regulations in partnership with the relevant international bodies. I’m aware of similar efforts in the energy industry, do you know of any in the maritime industry?