Isolationism’s impact on the global supply and demand of Harvard Business School’s students

Isolationist policies are reducing business school applications from students outside of the US, and dropping the number of graduates who accept positions abroad. How can Harvard Business School retain its prestige in a world where the greatest business opportunities lie outside of the US?

Harvard Business School (HBS) is at risk of losing their supply of international students to isolationist policies that make it difficult for them to attend school, acquire US work visas upon graduation, and for companies to risk hiring them. This distances HBS from international business communities as they grow to rival the US in size and importance.

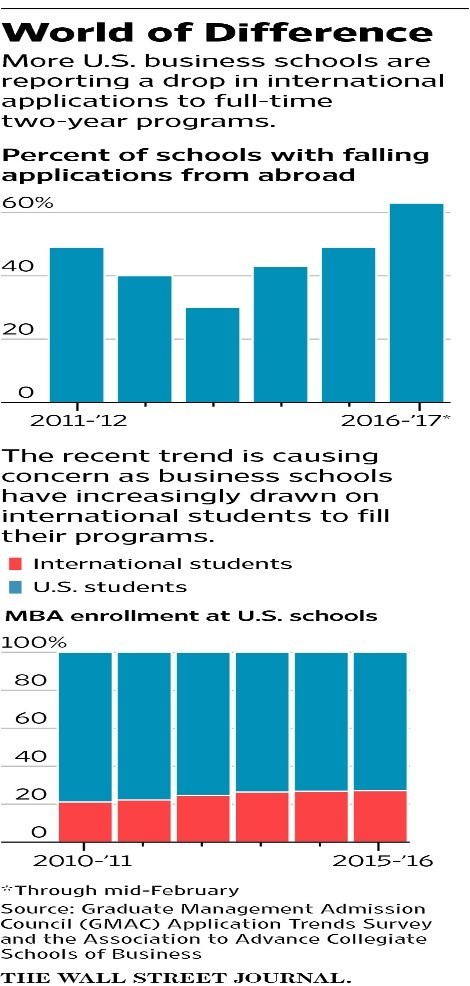

International students are hesitant to study in the US because of the political climate and fears of finding employment after graduation (Figure 1 [[1]]). 75% of US MBA programs saw a decrease in international applicants in 2016, despite 10% growth in overall GMAT test volume and 20% growth in international GMAT test volume since 2013 [[2]]. Those who do apply face a discouraging commercial and political climate, as a 2017 survey indicated 27.5% of US employers would hire international students, down from 34.2% in 2015 – and this survey was conducted before the White House presented an aggressive agenda on immigration reform [[3]][[4]].

International Applications to US Business Schools

HBS must expand its international influence to retain its status. The Harvard Business Review’s attempt to objectively identify the top 100 CEOs in the world found 54 to be helming companies headquartered overseas – this proportion will surely grow as GDP and population growth of the developing world outpaces the US [[5]]. Despite this trend, only 13% of HBS hires in 2017 accepted offers from companies based outside of the US – down from 17% in 2013 [[6]]. It is clear that business schools depend on successful alumni to attract students and provide financial support – the aforementioned trends indicate HBS will lack alumni in key growth markets in the years to come [[7]][[8]].

HBS has taken proactive steps to increase international exposure through the Field Global Immersion (FGI) program, the Global Initiative and it’s 14 global satellite offices. FGI is a 1-week consulting program in another country – firsthand exposure that is critical to convincing MBAs to work abroad [[9]]. The Global Initiative supports research and finds partners for the FGI program [[10]]. These efforts abroad do well to recruit students when US corporations dominate the world and there are reasonable prospects of international students working in the US; however, the value proposition breaks down when isolationism eliminates these prospects or when top firms originate overseas.

It is evident that Dean Nohira understands this trend, having stated, “if the 20th century was the American century, the 21st century will be the Global century, and one where game-changing ideas and radical innovations will emerge not just from the U.S., but from all over the world [[11]].” However, the rise of isolationist policies means HBS must accelerate global outreach, spreading alumni to leading companies around the world. HBS can circumvent these policies by exporting MBA students. When HBS alumni head successful companies overseas it exposes prospective students to the HBS name, and sends the message that one must not acquire a visa or work in the US to profit from an HBS MBA.

The question becomes how to encourage students to work abroad. For starters, HBS should incentivize students to spend their summer internship overseas with a supplemental grant. Second, satellite campuses should be retooled to prioritize business outreach over research, with the intention of building relationships with top firms and encouraging worldwide recruitment in Boston. Finally, class size should grow to support the larger international market, and the percentage of international students should increase to pace global growth trends.

A truly international institution must extend beyond business partnerships and student recruitment – it must also increase international faculty and facilities to support this venture. The challenge will be how to support this expansion without diluting the quality of the product.

(Word count: 799)

[1] The Wall Street Journal, “Red Flag for U.S. Business Schools: Foreign Students Are Staying Away,” https://www.wsj.com/articles/red-flag-for-u-s-business-schools-foreign-students-are-staying-away-1493819949, accessed November 2017

[2] Graduate Management Admission Council, “GMAC 2017 Application Trends Report – Web Version,” https://www.gmac.com/~/media/Files/gmac/Research/admissions-and-application-trends/2017-gmac-application-trends-web-release.pdf, accessed November 2017

[3] National Association of Colleges and Employers, “Plans to Hire International Students Slide Again,” http://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/candidate-selection/plans-to-hire-international-students-slide-again/, accessed November 2017

[4] BBC, “Trump backs proposal to curb legal immigration,” http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-40804841, accessed November 2017

[5] Harvard Business Review, “The Best-Performing CEOs in the World 2017,“ https://hbr.org/2017/11/the-best-performing-ceos-in-the-world-2017, accessed November 2017

[6] Harvard Business School, “Trends – Recruiting – Harvard Business School,” http://www.hbs.edu/recruiting/data/Pages/trends.aspx, accessed November 2017

[7] Harvard Business Review, “The Power of Alumni Networks,” https://hbr.org/2010/10/the-power-of-alumni-networks,” accessed November 2017

[8] Greenberg, Jason and Fernandez, Roberto M., What’s the Value of Social Capital? A Within-Person Job Attributes, Offer and Choice Test (July 14, 2014). MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 5141-14. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2465908 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2465908

[9]Fortune, “Harvard’s grand experiment: Send 900 biz students abroad,” http://fortune.com/2011/12/15/harvards-grand-experiment-send-900-biz-students-abroad/, accessed November 2017

[10]Harvard Business School, “HBS Global Initiative & Research Centers – MBA – Harvard Business School,” http://www.hbs.edu/mba/academic-experience/blog/post/hbs-global-initiative-and-research-centers, accessed November 2017

[11] Harvard Business School, “Messages from the Dean – About Us – Harvard Business School,” http://www.hbs.edu/about/leadership/dean/Pages/message-details.aspx?num=2671, accessed November 2017

Super important topic, thanks for writing about this! While I agree that programs like FGI and the push to include a greater share of international cases in the curriculum help broaden students’ exposure to business outside the United States, changing mindsets of US companies by starting from business school students is likely the slower route of adaptation. The more effective place for HBS to engage is likely through truly developing into an international institution. Rather than growing class sizes at the Boston campus, I think it makes most sense to add campuses in strategic international locations. The Boston location is already quite large by business school standards, and expanding the size of this campus would not solve the hiring problems that you identify in the article, at least in the near term. As you point out, the risk here is that the brand and quality of the business school could be hampered, but there is precedent for international campus expansion (e.g., INSEAD), and the appeal of teaching at HBS would likely attract top-quality faculty abroad.

A truly interesting topic. I do agree that an isolationist policy is very likely to negatively impact international students staying in the U.S. upon graduation. I think it is also worth to consider that, given the high economic growth and opportunities in developing countries, many international students are already considering to move back to their home country after graduation, regardless of the immigration policy in the U.S. It is very true though, under an isolationist policy, the portion of students that decide actively not to stay will very likely increase.

However, I will argue that this might not be a bad thing for HBS in the long run. More students leave the U.S. (due to a stricter immigration policy) to pursue careers internationally will also mean that the HBS network become much more wide spread (as opposed to concentrated in the U.S.) in the long run. As more and more global 500 companies are outside of the U.S., it might be a good thing that international students go back to their home countries (which might be an unexpected side effect of an isolationist policy) and lead the growing organisations in their home country – in which HBS will also benefit in the long run as a global institute.

As an international student, I am overly invested in this very topic. I agree that HBS should look towards globalizing their classes and curriculum more, but question the impact of satellite campuses abroad. For example, Yale-NUS in Singapore was Yale’s first international campus and also serves as Singapore’s first liberal arts college. However, many Yale faculty members have refused to teach in Singapore due to the perceived lack of human rights/ freedom of speech in Singapore. Yale-NUS students mostly come from Asia, and on some level it seems to be more of a money maker for Yale rather than a way to break free of the recent American isolationism sentiment. In that context – a second question I ask is, what is the role of a satellite campus to educate others in other parts of the world? How much of satellite campuses are for commercial, rather than educational, gain?

I wonder also about the role that HBS has in educating leaders about how to handle critics of globalism and, especially for those going into COO-type positions, how to handle and motivate employees who might retreat to isolationism due to labor-intensive jobs leaving the US. Our jobs will probably be safe from globalism or digitization, but what responsibility do we have as future leaders to think about the pressures of the people we will manage in the future?

Absolutely fantastic!

As a non-U.S citizen myself I do agree that increasing the number of international based cases would benefit the entire HBS population. However, I think the isolationism has affected U.S citizens more than international students. firstly, the curriculum is indeed focused on US companies but international students already have a non-US experience, or at least by the time they graduate from HBS they have the US and their own countries perspective. secondly, as a citizen of an emerging country I realize the potential of my country and therefore would rather be going home than staying in the US, which is something that HBS does not indicate in its CPD programs, the potential in emerging countries, and the better paying job, which US citizens lose out on. I think other ways to reduce isolationism is to increase the number of treks that are sponsored by HBS and to host international alums who have made it in other countries and write cases about them and finally highlight the payment potential in other countries in CPD programs.

Jim Holden, thank you very much for your article, it was a very interesting read. Being an international student myself (and being aware of the characteristics of my home culture), I would like to discuss the drawbacks of making HBS a more international university.

Although I believe that the leaders of the future need to develop a global perspective, I am also of the opinion that disproportionately increasing the amount of international students at HBS can have a significant impact on the financial viability of the organization. According to HBS’ annual report, the School received more than $161 million in new gifts and pledges during the year, which is 20% of total HBS’ revenue and 1.3x the amount of money the university collects from MBA students. The annual report acknowledges the importance of such gifts and donations coming from more than 12,800 donors (approximately 27 percent of the School’s MBA alumni).

Having a quick look at other statistics, I have learnt that the US is the country whose citizens, by far, make the most donations as a % of GDP (1.44% vs. 0.5% in the UK, 0.37% in India or 0.03% in China). This leads me to believe that if the university disproportionately increases the amount of international students, who come from cultures were philanthropy is not as engrained as in the US, the amount of money available to invest in the program coming from alumni would probably be restricted.

I am not saying HBS should not embrace and foster internationalization, I am just trying to raise a potential challenge the institution might face if that’s the focus going forward.

Source: Charities Aid Foundation, HBS annual report

The quote from Dean Nohria about the Global century raises the question of what Harvard Business School’s objective truly is. While both the article and multiple comments lean towards international campuses as an answer to maintaining global relevance, I worry that the impact would be diffusing the global elements of the HBS experience. I believe that global relevance comes from the experience that students leave with, especially because employers care about access to employees who are prepared to deal with the global business environment. Though FGI is an avenue to enhancing students’ global perspective, it is likely insufficient for the skills that many MBAs will need.

HBS’s core is still the case method. Therefore, a reemphasize on global business starts with the cases that are selected. Rather than a particular situation to be analyzed, being part of or managing a global team should be a significant focus. In addition, HBS should look at its faculty to makeup to ensure that international experience is well represented. By ensuring both international and domestic students gain the global experience necessary to succeed, HBS can continue to lead in the Global century.

Thank you for writing this.

As an international student whose country represents 1% of the total class, let me tell you this: I am having a great international experience – I am living abroad in a new country, and 99% of my class is international to MY eyes. This couldn’t change even if the non-U.S. student population became lower as a percentage of the total, as long as I still have the same probability of entering the program. And just like Swan said, the restrictions for working in the U.S. after just mean I will probably have to go somewhere else, which may still be good for HBS’s global footprint in the long term. In addition, the most demanded post-MBA jobs are still very open to visa sponsorship.

The big losers from this are the U.S. students themselves, but only in terms of their MBA experience (we’ll see the long term in a second). Decreasing the international composition of the class will only impact their own exposure to global cultures. Moving everyone to a campus in, say, France or Singapore for a whole semester will not help at all. It would be an immense expenditure which could work as a marketing point to boost applications, but not much more. It could even be detrimental, as I feel that at Aldrich is where the real magic of having almost 1000 people sitting in U-shaped rooms and discussing the same topics takes place. I do agree on the point that more cases should be international, and also that recruitment should be more international as well.

But if we think of HBS as part of a supply chain for human capital, I think it simply means that the ‘product’ (us) cannot be placed in a market as easily as before. Immigration and job market restrictions, in essence, are just like trade restrictions. If we think macro-wise and aggregate all grad students of all universities, this means higher costs of factors for production in U.S. firms (management and executives salaries) and probably a redistribution of wealth from the poorly educated to the highly educated in society (think for instance how competitively priced legal professional services would be for blue-collar workers if there was a near-infinite supply of lawyers and bar exams did not operate partly as a barrier for entry). It’s an interesting source of wage security for incumbent U.S. residents with an MBA. And long-term, the State is simply offering protectionism for the best educated in society. Therefore, U.S. MBA students will reap benefits from this policy in terms of income. It is unclear whether the decrease in competitiveness from the lack of international exposure will have an offsetting effect on the future income prospects of these students.

Very interesting article! As a current MBA student, this was extremely relevant and a perspective that isn’t discussed frequently. HBS finds itself in an interesting tension, with the US growing increasingly isolationist but global companies are gaining more relevance and importance. As HBS considers how to expand it’s efforts overseas, it seems a critical player to get involved is Career & Personal Development (CPD). A big driver in the jobs MBA’s apply for is the funnel of jobs presented on campus and through the CPD website. I wonder if the percentage of job postings has reflected the macro shift or if HBS has made efforts to counteract these trends through CPD outreach.

A key assumption that this article relies upon and needs to call into question is whether or not global business growth will be driven by U.S. companies expanding overseas or new domestic entities forming in their own countries. If a large portion of international business and job growth were to come from U.S. corporations, such as big brands and professional service organizations growing new locations and offices in other countries, then the U.S. business schools could possibly be more protected. For a long time, international markets have been flooded by U.S. firms expanding, which drew talented international business students to come to the U.S. to get the education that would send them back to these firms’ international offices in their home countries. For example, a Japanese student may choose to come to Harvard Business School to recruit for the McKinsey Tokyo office. But as international students see more opportunity for businesses at home, they might be more likely to stay in their country for their education. The trend seems to be that international businesses are developing to compete with the U.S. corporations, and that may be a major reason that international applicants are down, aside from any visa or immigration issues.

Jim- Great article and very interesting to read!

I agree that issues with immigration will have a detrimental impact on the diversity of students at HBS. Given the fact that the case method relies on diversity of experiences to work, this impacts HBS perhaps more than any other business school. Also, policy is making it challenging for international students who hope to work in the US after graduation. This may decrease interest in coming to a U.S. school and having limited options with companies recruiting on campus. That being said, I am not certain programs like FGI and encouraging work abroad is the only solution.

While I have concerns about the impact of satellite campuses on brand dilution, I also think that HBS needs to disrupt itself to stay ahead of global trends. While things like online universities still have some stigma associated, HBS has taken on the HBX program as a way to extend its reach. Part of that includes classes and meet up at the Boston campus. While the program is not a degree program, careful use of the platform can generate significant interest as a marketing as well as educational tool. In addition, capital cost of adding an international campus does not exist with the platform and improvements in technology can replicate a live case discussion experience. Initiatives like these will help increase HBS visibility and keep the name top of mind for potential students.

Really interesting read – thanks for writing! While I agree that this is something business schools are grappling with, I do think our political contexts makes me questions whether this is a long-term issue or short-term issue. Isolationist policies, immigration, and global perception of the United States are all contingent on the political climate and the administration in house. In fact, Pew research reported that immediately after the election, favorability about the U.S. fell amongst most countries except Russia. Given our political system, it is easy to see that the gravity of the issue may increases or decrease every 4 years. As a result, we see international engagement as a component of the HBS education, but it seems that the leadership prioritizes it after other threats in the education sphere (i.e. online education, interconnectivity with other Harvard campuses, etc.) Moreover, Axios indicated that the impact of these policies is heavily tiered towards the mid-tier and lower-tier business school programs. It would be important to dissect the data by the level of program prior to drawing the causality relationship.

Broadly, I agree that HBS can do much more with regards to exposure to international contexts. While FGI is a great addition to the curriculum, competitors (University of Michigan – Ross School of Business among others) actually offer a similar opportunity for a complete semester. It is difficult to have a truly immersive experience that can provide one with adequate understanding of what it’s like to operate in a business capacity in another country only through a week long experience. There is an opportunity to create a much more powerful experience through FGI. Additionally, there are other ways to incentivize students to work abroad. Another solution that comes to mind is cases – how many cases have protagonists in other countries? I can name a few LEAD cases where we were reminded to think about the cultural context of the country, but I would imagine that there is opportunity for more.

Fascinating topic.

I would suggest that there is a linkage here to a domestic issue that should also be addressed: namely, the perception of elitism that comes from HBS and schools like it. There’s no denying that the last 18 months have been – if nothing else – surprising in terms of global public opinion shifts. In many cases, these movements seem to come from legitimate pain felt by large numbers of people that then use HBS and its peers as a foil to explain why things have turned out as they have. I think it’s important that we realize that as long as HBS remains to be seen as a conduit to jobs at Goldman and McKinsey, instead of a place full of people who truly care about making a difference in the lives of everyday people, that this avenue of criticism and the backlash that results will remain open.

In short, HBS needs to put a greater emphasis on public service, and not simply sit back and let HKS do all the public sector work. Then, and probably only then, will we have the leverage to make an effective counter-argument when isolationist trends threaten the HBS business model.

Like many of the other commenters, I am an international student myself, and I believe this is a critical issue for both HBS and Harvard at large. This is precisely why I think HBS needs to join forces with Harvard more broadly as well as other universities. I agree that it is important for HBS/Harvard to educate its student in a way that fosters an “international” mind (e.g. through programs like FGI), but I also believe that the fundamental issue as far as HBS’/Harvard’s own “supply chain” is concerned are the recent changes and potential future challenges in immigration policy that might prevent international students from attending Harvard. Harvard has already filed a number of amicus briefs to oppose recent shifts in immigration policy under President Trump. However, I think the university needs to increase its efforts, and HBS should play an integral part in that. It should leverage its extensive alumni network and contacts across universities, politics and the business world to help shape the public and the policy discussion as much as possible. No matter how much HBS/Harvard might increase its efforts abroad in order to train their students to think more globally, the foundation of a truly international education is the diversity in the class room that shapes students’ learning experience every single day.

Absolutely love the topic. I do agree that HBS should influence students to work abroad more.

I think another hurdle is not only for HBS to improve its curriculum to be more international, but also influence companies outside the US to appreciate the value of an MBA students and letting them know how to best position a MBA student in an organization. Coming from Asia, and planning to go back to Asia in the long term, this is the biggest concern I have.

I personally find it is very difficult for me to leverage my degree to recruit for a non-Finance or Consulting firm outside US. US employers are better trained in how to best utilize the value of an MBA students, there are structured programs and standardized pay. However, many employers from Emerging market like big tech firm in China seeing MBA students just like many other master degree student and only value their pre-MBA experience in their hiring criteria.

One thing the school could do better is leveraging on HBS student’s network to establish a relationship with big firms outside US on either research topic or collaborative projects.

Amazing read! Thank you for sharing with us such an important topic. As an international student, I strongly relate to what you have written. As you’ve mentioned, this is a two-way street – spreading alumni overseas but also maintaining international alumni within the United States. I am lucky enough to have a dual-citizenship and not to worry about a working authorization following graduation but as I watch my friends that are here on student visas I realize the great risk they took in coming to HBS. Unfortunately, the current government has been imposing many constraints on internationals who would like to stay and work in the US following graduation. This is causing many international prospective students to re-think their desire to join HBS in the future as they do not necessarily see the value of coming to HBS and then returning to their home country. I want to raise another issue – although HBS claims to have 34% international students, the majority is students with dual citizenships that have been living in the United States for most of their life. In order to increase diversity, I believe the number of international students that have spent most of their lives outside the US should be increased to stress the diversity. As mentioned above, the international faculty members should be increased as well. I believe that HBS has its methods to maintain the high quality of its product but even at a cost of affecting the product’s quality it is worthwhile to bring more global experiences and influence into the classroom.