Is the Navy’s Additive Manufacturing Strategy Bold Enough?

The line between disorder and order lies in logistics…

– Sun Tzu

The success of the U.S. military will be defined not only by its capabilities, but also by its ability to rapidly scale and adapt its supply chain. Additive manufacturing (AM) has the ability to augment supply chains for defense organizations, solving problems that have plagued the military’s supply and maintenance chain for decades. [1]

Importance of Additive Manufacturing in Naval Supply Systems

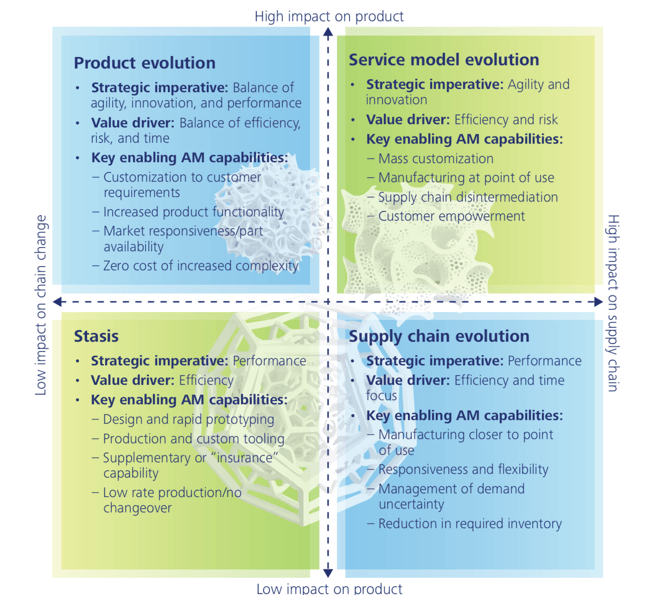

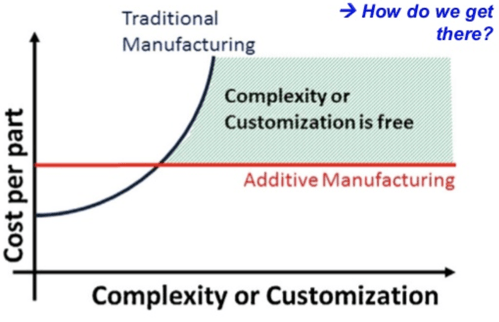

During extreme conditions such as deployments in remote locations, supply chain management is vital to the success of a mission. An asset touches several points along the military supply chain before landing in the end-user’s hands. This consists of “millions of parts and thousands of geographically dispersed suppliers,” creating a complex supply chain system [1]. Additive manufacturing in supply chains could skip these steps by enabling a CAD-to-ship solution, categorized as a supply chain evolution in Exhibit 1 (bottom right quadrant). A Deloitte study expounds on the impact of AM by providing three additional paths of AM for the DoD – Product Evolution, Service Model Evolution, Stasis, and Supply Chain Evolution (Exhibit 1) [1]. Further, an MIT study on AM helps explain when it becomes a viable solution, which is particularly important for complex parts and systems as well as customizable parts and systems. Both of which are common in the Department of the Navy (DON) supply chain [5].

Exhibit 1

Source: 3D Opportunity in the Department of Defense, Deloitte

Exhibit 2

Source: MIT Additive Manufacturing

The DON is pursuing all four of the quandrants seen in Exhibit 1 to tackle some of the Navy’s biggest problems, which include obsolescence, customization, and product lead-times [1]. For example, the Navy’s F/A-18 Super Hornet, regarded as a premiere aircraft vehicle, is slowly being phased out as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) replaces it. A typical F/A-18 aircraft lifecycle is 6,000 flight hours, but its lifecycle is being prolonged to 10,000 flight hours after JSF production was delayed [6]. As the DON changes these assets’ lifecycles, they must be prepared to deal with these logistical challenges, all of which can be solved with the introduction of AM.

Short Term Solution

Currently the DON has marketed the below solutions to the public, meaning these are the most viable solutions to be used fleet-wide.

- Print the Fleet Initiative with 3D Systems [2]

- Parts on Demand Secure Weapons Information System [1]

- USS Stennis 3D Printing Center [7]

Long Term Solution

The ideal solution for NAVSUP is to integrate AM with parts production and supply integration, occupying the top-right/fourth quadrant in Exhibit I, increasing the number of iterative designs that can be adapted real-time in the field. Right now, the Navy is approaching AM with a risk-averse strategy, focusing most of its energy in the Stasis category. They are using test programs like the USS Stennis listed above and tackling more systemic issues before fully integrating AM into the Supply Chain process [1].

Recommendations

The acceleration of change in the defense industry is slow, dependable, and methodical with a development cycle lasting several years [1]. I worry that the adaptation is too slow in today’s aggressive, expansive technology environment, and I am concerned that the Navy supply enterprise is not taking the opportunity to seriously develop AM capabilities into their supply chain. In the latest Supply Corps Newsletter, 3D printing is still described as a technology in its infancy despite being around since the 1990s [3, 8]. Further, future initiatives seem to shy away from ambitious rethinking of the supply chain, focusing instead on information technology changes and responsive contracting [4]. These are important initiatives but can be completed in conjunction with bold innovative thinking such as full AM fleet-wide.

Unless these bold strokes permeate throughout the DoD structure, I fear that the Navy will be playing catch-up against our adversaries, missing out on the opportunity to overcome existing problems and jump into an innovative solution that will give the DON a competitive advantage for decades. My recommendation would be to rapidly scale low-risk pilot programs. The USS Stennis lab is a great start to AM in solving lead-time reductions and design iteration problems. The DON should push for these innovative solutions system-wide across the supply chain, adding more breadth to this pilot program.

With the test programs in mind, is the US Navy pushing innovative technology to the forefront fast enough? Should it?

(Word count: 727)

[1] Lewis, Matthew J, et al. “3D Opportunity for the Department of Defense.” Deloitte United States, 20 Nov. 2014,

www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/3d-opportunity/additive-manufacturing-defense-3d-printing.html.

[2] Kohlmann, Ben. “Providing Rapid Response Solutions for the Fleet through 3D Printing.” USNI Blog, 23 Apr.

2014, blog.usni.org/posts/2014/04/23/providing-rapid-response-solutions-for-the-fleet-through-3d-printing.

[3] Hoffman, Tony. “3D Printing: What You Need to Know.” PCMAG, PCMAG.COM, 20 June 2018,

www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2394720,00.asp.

[4] Benson, Benjamin. “NAVSUP Reform Is Making Way.” The Navy Supply Corps Newsletter, Sept. 2018, pp. 9–10.

[5] Hart, John. “Additive Manufacturing MIT 2.008x.” https://www.slideshare.net/AJohnHart/Additive-

Manufacturing-2008x-Lecture-Slides, 21 Nov. 2016.

[6] Myers, Meghann. “Officials Extend F/A-18 Hornet Service Lives.” Navy Times, Navy Times, 7 Aug. 2017,

www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2015/03/07/officials-extend-f-a-18-hornet-service-lives/.

[7] Katz, Justin. “Stennis to be first aircraft carrier with additive manufacturing lab” ProQuest, 21 Aug. 2018,

search.proquest.com.ezp- prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/2090266780?accountid=11311.

[8] Stamatopoulos, Peter RDML. “Maritime Logistics in a Changing Strategic Environment” The Navy Supply Corps

Newsletter, Sept. 2018, pp. 24-34.

Great article! I understand your view that a rapidly-changing landscape demands a flexible supply chain, but I also wonder how the Navy can control inventory proliferation if it decentralizes production-making? For ease of argument, let’s say we start making M4 clips in the field with 3D printers. You’d have an approved blueprint, an approved machine, and approved materials that you’d combine to produce a printed clip. Wouldn’t that make the supply chain more complicated though because the Navy would then have to stock all the components required to make the clip to begin with (ie molds, liquid metals, etc.) instead of only stocking the finished product, so you’d see a huge proliferation of SKUs if applied to multiple products? If so, then is the potential of 3D printing mostly limited to stateside production instead of field production?

This is a fascinating post! I’m curious how this will affect the Navy’s relationship with long-time suppliers to our armed forces. Several large defense contractors are not only an important strategic partner to our armed forces but also have a large impact on the US economy. Maintaining their capabilities is an important part of readiness should the US find itself in a major conflict and have to draw on their skills and capacity to produce new or additional products for defense purposes. These contractors have a symbiotic relationship with our armed forces for the most part, and may hold patents on some of the technologies currently being deployed. Is there a way to deploy additive manufacturing in a way that is sensitive to these existing relationships and their broad impact on our economy? How should the US Navy best partner with its suppliers in order to create a high-quality, cost-effective, and efficient supply chain while also being sensitive to the role of the private defense sector in our economy?

Very interesting and as the Navy works out the kinks, I am sure this will ultimately improve readiness of the Fleet and the ability to minimize port visits to retrieve components. I am curious about a few other challenges. One specifically, is who is going to be qualified to operate the 3D printers and commensurate to that is, who (contractors maybe?) will be providing the CAD blueprints and materials. The Navy will have to figure these out before real headway can be made. Additionally, how will the Navy deal with a redundancy issue that this shift would create. For instance, if the Navy logistics chain relies on AM to replace parts on ships, what parts will the Navy hold in inventory.

Very cool topic Devin! Thanks for sharing. One question that popped into my mind is how cost effective 3D printing in this context is. I would imagine that while 3D printing presents many speed-related benefits, the cost of highly complex additive manufacturing is still very high, if not prohibitively show, as compared to traditional manufacturing. Who do you think should bear the costs? In addition, is there a way for the Navy to gain expertise through partnerships rather than internal development? It sounds like one barrier to adoption is the existing supply chain structure that current operators are used to and may be difficult to flip. Could the Navy instead join forces with a more nimble private corporation that is more equipped to make headway?

Very interesting, thank you! In a similar vein to the comments above, I’d be interested to know whether a shift to additive manufacturing in the Navy would result in private contractors being less incentivised to invest in research and development. If they were concerned that the Navy would be looking to manufacture any new innovations at a lower cost through additive manufacturing, they may focus their innovation (and funds) elsewhere, which may be harmful in the long-term.