Is French most cherished tradition at threat because of Climate Change?

French winemaker pushed to innovate to fight the global warming impact on the quality of their wines.

Some of the most famous wines, that we enjoy drinking in France but also everywhere else in the world have entered a phase of transition that could lead to significant changes in their taste, acidity and alcoholic levels over the coming decades.

Indeed, the specificities of wines coming from different varieties and Chateaux is the result of complex combination of soil composition, weather conditions (temperature, light, moisture) and manufacturing process.

In the last five years only, France has known three of its warmest years since 1900 (2011, 2014 and 2015)[i] and received less than 90% of its average precipitation in 2015 (one of the ten driest years in the last fifty years)[ii]. Looking at the Bordeaux region, the temperature has increased by one degree Celsius on average since the 1980s[iii]. The main impact of global warming on the wine production is the acceleration of the grapes ripeness process (two to three weeks less than 30 years ago). In an environment where the grapes are exposed to too much light and to high temperatures, they tend to reach what winemaker called “sugar ripeness” (ideal sugar level for wines to get to right level of alcohol and acidity) before the physiological ripeness (when the harvest should occur to get the right level of astringency).[iv]

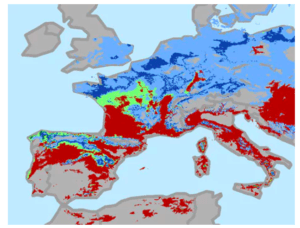

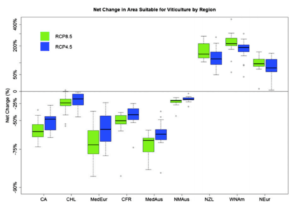

The shortening of the harvesting process is diminishing the quality of the wine and if the temperatures keep increasing at the current rate, the surface area suitable for viticulture could significantly decrease. According to a study lead by Lee Hannah in 2013[v] (see exhibit 1 and 2), under the RCP (Representative Concentration Pathways)[vi] 4.5 scenario, the suitable area in Mediterranean countries would diminishes by 60% and by 73% under the RCP 8.5 scenario, with French regions of Bordeaux and Rhône being extremely affected.

For the purpose of this study, I have selected a Chateau from the Bordeaux region that has been a precursor in trying to tackle the impact of climate change on the quality of their wine. Since 2008, The Chateau Suau has transformed its production process to match the standards of the French organic agriculture. Since then, the Chateau Suau uses only pure natural products for its entire process. Hence, common winery diseases are no longer treated with pesticides but with minerals such as copper and sulphide[vii].

The main benefit of organic viticulture is that it stimulates the soil biological activity and improves its physicochemical properties leading to an enhanced fertility with a higher soil stability[viii]. While this technique certainly provides the Chateau Suau with a competitive advantage and a higher resistance to climate change, organic production will unfortunately not be enough if the scenarios described previously were to occur.

Additional measures that can be considered are as follow.

- Improve water management especially in period of drought. Some wineries in the United States have been experimenting some processes to re-use waste water (six gallons of waste water are produced when making one gallon of wine)

- Increase the foliar surface of the vine to better protect the grapes from the rising temperatures and try to extend their maturation cycle[ix],[x].

- Relocate the vines towards plots that are less exposed to the sun or oriented North. However this solution is seriously constrained by the specific geographic delimitations for each wine variety in order to be classified as AOC – controlled designation of origin[xi]. This classification is extremely important in determining the sales price of the wine.

- Develop new grape varieties that are more adapted to the new climatic conditions. The Bordeaux Wine Board has been lobbying to change the AOC regulation to grow some varieties that are currently barred on a small part of their plantation (one to two percent)

If France waits too long to modify its long-standing AOC standards that are the guardian of its precious heritage, could it lose its supremacy in the wine production towards Northern European countries such as the United Kingdom?

659 words

[i] National Centers for Environmental Information of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Global analysis report for 2015”, Nov 8 2016, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/201513

[ii] National Centers for Environmental Information of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Global analysis report for 2015”, Nov 8 2016

[iii] Rudy Ruitenberg, “The Way That France Makes Wine Is About to Change Forever”, Bloomberg, Oct 15 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-10-15/merlot-faces-the-heat-as-bordeaux-seeks-climate-proof-vineyards, accessed Nov 1 2016

[iv] Jamie Goode, “Viticulture: Fruity with a hint of drought”, Nature, Dec 20 2012, http://palgrave.nature.com/nature/journal/v492/n7429/full/492351a.html, accessed Nov 2 2016

[v] Lee Hannah et al, Climate change, wine, and conservation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 10.1073/pnas.1210127110, April 8, 2013, http://www.pnas. org/content/early/2013/04/03/1210127110

[vi] Wikipedia definition: Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) are four greenhouse gas concentration (not emissions) trajectories adopted by the IPCC for its fifth Assessment Report (AR5) in 2014.It supersedes Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) projections published in 2000. The pathways are used for climate modelling and research. They describe four possible climate futures, all of which are considered possible depending on how much greenhouse gases are emitted in the years to come. The four RCPs, RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6, and RCP8.5, are named after a possible range of radiative forcing values in the year 2100 relative to pre-industrial values (+2.6, +4.5, +6.0, and +8.5 W/m2, respectively), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Representative_Concentration_Pathways, accessed on Nov 2 2016

[vii] Château Suau, “Knowledge”, http://chateausuau.com/fr/vignobles-francais/, accessed on Nov 2 2016

[viii] French Institute of vine and wine, “Organic viticulture”, http://www.vignevin-sudouest.com/publications/fiches-pratiques/viticulture-biologique.php, accessed on Nov 2 2016

[ix] Chateau Grand Francais, “Is Global warming impacting organic wine?”, http://www.grand-francais.com/rechauffement-climatique-vin-bio/, accessed on Nov 2 2016

[x] French Institute of Vine and Wine, “Report on management of the water regime of the vine”, Jan 15 2014

[xi] Laurent Abadie, “The Bordeaux wine region is preparing for global warming”, Sciences et Avenir, Nov 13 2015, http://www.sciencesetavenir.fr/nature-environnement/le-vignoble-bordelais-se-prepare-au-rechauffement-climatique_17157, accessed on Nov 2 2016

Great overview of a problem that I selfishly hope the wine industry takes a serious stand against in the very near future to save the future of wine! However, one question that I have as a result of reading your post is how these organic agricultural processes affect the quality and taste of the wines. Do they have much of an impact to consumer? Would the consumer even be able to note the difference in a bottle of wine? If so, I think companies that shift to this methodology as a way of combating climate change will need to tread lightly and work to communicate these changes to their consumers so that they don’t inadvertently kill their demand.

It’s clear from your post that the wine production process requires some serious changes in the coming years. My first thought is that other regions of the world may take over as viticulture leaders as their respective climates evolve from their present conditions to levels that foster simultaneous sugar and physiological ripeness. My second thought is that perhaps it would be a really great investment to start buying some great French vintages while they still exist … I just hope that nothing affects your cheeses!

In reading this, two thoughts come to mind. First is going back to our Indigo case. I wonder if the technology they are using in wheat and other grains could be applied to grape vines as well. My second thought is with changing too much in the wine industry there might be resistance from the vineyard owners. In my limited experience with French vineyards, they are family owned and go back generations so I can’t imagine that they would be too willing to make drastic changes to their operations.

It’s fascinating how strict AOC regulations were laid out and generated exclusivity based upon geographical definition. It’s quite a masterful move in generating exclusivity, because the geographical definition precludes others from being able to compete, even if they use similar viniculture techniques or generate similar flavor profiles and blends of wine as the originating Chateau. I question whether there will be a significant shift in viniculture to Northern Europe and the U.K. in the next few decades, given the lack of expertise or cultural background in the field. In the near term, I expect the impact is more likely that there simply will not be many good wines to be had. While it may certainly hurt the industry reputation and devastate some connoisseurs (e.g., the whole population of France), I would expect that the French Chateaus will retain their leading position in the near term, long-enough for them to innovate and adapt.