In a torn up town, no post-code envy: The New York City Housing Authority

Operating sustainably for the sake of climate justice

As it wreaked havoc across the Atlantic Coast of the United States in October 2012, Superstorm Sandy took with it lives, homes and businesses causing an estimated damage of over $25bn[i]. The hurricane left behind a clear message: the debilitating effects of global warming are here to stay[ii]. Perhaps more importantly, the destruction demonstrated that even in a developed country like the United States, low income communities are disproportionately vulnerable to the consequences of climate change.

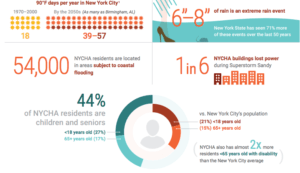

In New York alone, 270,000 low-income households and 97,000 senior households were directly in the storm surge of Hurricane Sandy[iii]. The storm impacted 10% of all public housing units in New York City, leaving approximately 400 buildings without electricity, heat and hot water. The single entity that was had to bear $3bn[iv] in damages as a result? The New York City Housing Authority, or NYCHA, which administers public housing in the five boroughs of New York City.

NYCHA’s Need for Sustainability: Now or Never

The New York City Housing Authority is the largest public housing authority in the United States with more 400,000 low-to-moderate income residents in mostly in poor-quality, aging buildings. Climate change is an important consideration for NYCHA because the White House’s National Climate Assessment recently found that extreme weather events such as hurricanes as well as the compounded stresses of ongoing heat, poor air quality, flooding and mental health disparately impact low-income communities that NYCHA serves. [v]

In addition to the burden on its residents, climate change is likely to exacerbate NYCHA’s costs through a number of channels, including:

- More power outages and physical damages to buildings due to extreme weather

- Increased building cooling requirements due to rising temperatures, and reduced efficiency of current cooling methods such as ventilation

- Higher humidity levels resulting in increased mold and decreased thermal performance

These risks present a monumental challenge to NYCHA’s operating model, which is particularly concerning given the housing authority’s bleak financial position. A combination of federal funding shortfalls and costly operations over the years have resulted in a current need for $17bn in capital improvements in NYCHA’s buildings.[vi] The incremental costs stemming from the effects of climate change means that NYCHA faces an immediate, real risk of receivership if it does not transform its operations.

A Long History of Sustainability

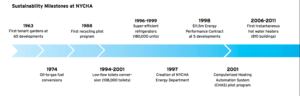

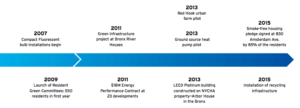

Because NYCHA depends on limited federal government funding for its operations, one of the ways in which it has achieved cost savings to-date has been by being a first mover in sustainability. The timeline illustrates NYCHA’s sustainability related milestones, dating back to the 1973 oil embargo. [vii]

Despite these measures, NYCHA has a very long way to go still. With technology advancements in energy efficiency, renewable energy, sustainable building design and recycled materials that offer NYCHA a unique opportunity to use sustainability as the tool to transform its operational practices and end its downward spiral and become financially solvent.

NexGen NYCHA Agenda

Realizing that the status quo was no longer viable, in early 2016, NYCHA announced its first ever ten-year plan to achieve financial stability. The cornerstone of this roadmap is a Sustainability Agenda to preserve public housing for the future. The agenda’s initiatives broadly fall into three categories:

- renewable energy and energy efficiency to install revenue-generating rooftop solar projects and upgrade heating and lighting systems through retrofit projects,

- construction and operations improvements by implementing stringent design and construction standards for new buildings, installing water meters and waste management through recycling and

- promoting healthy lifestyles through mold prevention and reduction of second hand smoke.

Notably, tangible goals set by NYCHA include a 30% reduction in greenhouse gases by and the development of 25 MW of renewable energy capacity by 2025[viii].

What next?

While the Sustainability Agenda lays out a detailed long-term plan and lofty goals for climate justice and resilience, given resource constraints, it is critical that NYCHA target its effort on immediately actionable projects. A successful implementation is contingent on strong partnerships with community organizations and the private sector for financing and project management. An ideal project that accomplishes the above is a community solar microgrid that will enable NYCHA to meet its target renewable energy capacity, create significant cost efficiencies and economically empower its residents. A microgrid offers NYCHA developments resilience during hurricanes while reducing dependence on distributed energy and fossil fuels. In addition, a community-led project would enable NYCHA individuals and community-based organizations to be co-owners of the solar project and create green jobs for residents. Lastly, a resident-driven initiative is that it will foster awareness for environmentally friendly practices and conservation in NYCHA’s communities.

(782 words)

[i] “Sandy and its Impacts” http://www.nyc.gov/html/sirr/downloads/pdf/final_report/Ch_1_SandyImpacts_FINAL_singles.pdf

[ii] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Report http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2013/20130905-extremeweatherandclimateevents.html

[iii] Enterprise Community Partners Report https://www.enterprisecommunity.com/resources/ResourceDetails?ID=0083708

[iv] Hurricane Sandy, Four Years Later: http://www1.nyc.gov/site/nycha/about/recovery-resiliency.page

[v] “Third US National Climate Assessment Report” http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/

[vi] Next Generation NYCHA Sustainability Agenda published by the City of New York Mayor’s Office and the New York City Housing Authority https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/sustainability_links_to_plans.pdf

[vii] Next Generation NYCHA Sustainability Agenda published by the City of New York Mayor’s Office and the New York City Housing Authority https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/sustainability_links_to_plans.pdf

[viii] Press Release titled “NYCHA Announces First-ever Comprehensive Sustainability Agenda for Healthy & Energy-Efficient Public Housing” released April 21, 2016 https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nycha/about/press/pr-2016/NYCHA-Announces-First-Sustainability-Agenda-20160421.page

First, a tip of the hat to the title of your post. Very clever.

The impact of increasingly frequent extreme weather events on public infrastructure and city budgets is certainly a vexing problem. Many local government are struggling to fit increasingly costly storm cleanup effects into annual budgets. $28 million for flood abatement at LaGuardi, $77 million annually for NYC snow removal, $177 million for debris cleanup after Sandy; it adds up. Then add in the unanticipated cost of accelerated wear and tear on public buildings, bridges, highways, etc. It seems unavoidable that local governments will need to devote ever increasing resources to combating the direct effects of climate change induced extreme weather.

You mentioned NYCHA had to bear the cost of $3 billion in repairs to public housing buildings after Sandy. Does the city hold insurance policies against this kind of major damage to public infrastructure?

Great post. Do you think it would be feasible to install smarter home systems (this is a bit extreme: http://www.investors.com/news/real-estate/apple-teams-with-builders-to-get-devices-bundled-into-smart-homes/ for “affordable” homes but it does give a good flavor of what could be achieved with smarter home systems) and do you reckon such systems might make a difference in fighting climate change impacts?

Excellent and enlightening post. I usually think of the public sector as being a late adopter when it comes to new technology so it’s interesting to see the housing authority as a leader in sustainable design. It does seem strange that it took the housing authority until 2016 (and $17bn in obligations) to start working on a plan towards financial stability — I’m surprised there aren’t more checks and balances to ensure capital improvements aren’t just pushed off indefinitely (likely leading to much larger costs down the road). I would love to hear from some of the international folks in our section how public housing works in their home countries if anyone could share!

I always ask myself the same question when I hear about publicly-funded environmental initiatives: how are we going to pay for it? Your post is quite informative with NYC’s plans, but I’m not sure that the municipal government will be able to get its act together to fund such an endeavor. Additionally, it’s often the case that a retrofit (as NYC plans to do with current NYCHA buildings) is more expensive than a new construction, as technology needs to be designed around existing architecture.

With that being said, I’ve heard alternate plans posit the following… Given that much of NYC public housing sits smack-dab in the center of prime (and super expensive) real estate, NYC would be better off selling the buildings to developers and using the proceeds to build state-of-the-art public housing facilities in less expensive areas of the city. The developers purchasing the existing buildings would have environmental mandates with which they must comply. Similar projects have already been undertaken (such as Stuyvesant Town & Peter Cooper Village on the Lower East Side of Manhattan) with great success. Of course, this plan brings up the obvious questions of whether it’s fair to force long-time residents out of their homes, even if the facilities would be an upgrade.

Anytime government initiatives are listed, I always look to the big question of how they intend to fund the programs and ensure they are sustainable. This is especially important when it comes to infrastructure relating to climate change, as the impact will in theory continue to get worse and an escalation of corrective actions will be required to address the growing problems. This is where the NYCHA has come up with the solution of revenue-generating rooftop solar projects in an effort to both cut down their energy reliance as well as potentially fund their own project and ensure it is sustainable. My question would then be what else can they do to ensure the initiative is sustainable? Is this single solar project sufficient to drive the other legs of the program, and for how long given potentially increasing temperatures and bigger storms in the future?

Fascinating article (and as a former New Yorker, very close to my heart!).

One of the great mysteries of NYCHA and affiliated entities is the amount of “off-book” work and capital still provided by NYCHA for non-NYCHA-owned properties. Naturally, this capital includes daily operating amounts as well as future investments, e.g., to ensure a source of renewable energy for the dwellings. A key example that comes to mind is Stuy Town, for which the city still pays a few hundred million a year to subsidize rent-stabilized property as well as ensure its longevity through investment in renovation and innovation. Given recent bankruptcies and sales, the new owners’ representatives are seeking more government help for investment in the future.

On reading your article, I couldn’t help but wonder about the ethical question NYCHA and local government sits in: despite the need to strike a balanced budget, should NYCHA be considering seeking additional government capital in order to ensure that the appropriate (and not just minimum) amount of funding is applied to on and off-book property affiliations, for the sake of the longevity of the city as a whole?