Fujifilm: Surviving the digital revolution in photography through diversification into cosmetics

“Kodak acted like a stereotypical change-resistant Japanese firm, while Fujifilm acted like a flexible American one.” -The Economist [1]

The digital revolution in photography has dramatically changed the way we take and share photos. As a child, I remember taking film to the store to have them developed, order extra prints, and physically placed them in our photo albums when we got home. Today, we can take photos with our smartphones and share them with anyone in the world in a matter of seconds.

Like every technological advance, the triumph of digital photography has created significant challenges for some industry players. Kodak and Fujifilm, manufacturers of photographic film, saw demand for their products sharply decline, causing Kodak to eventually file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2012.[2] Fujifilm, on the other hand, was able to survive by diversify their product portfolio by leveraging their photographic film technology to start making cosmetics – yes, you heard right, cosmetics.

Fujifilm and the Film Industry

A Japanese company founded in 1934, Fujifilm started manufacturing film for motion pictures based on a government plan to establish a domestic photographic film manufacturing industry.[3] In the 1960s, it began its endeavor to expand its business overseas, in an aim to catch up to the dominant industry leader, Kodak. In the 1980s, it became apparent to both Kodak and Fujifilm that the age of digital photography was right around the corner, and from a global peak in 2000, demand for camera film dropped 90% in 10 years as the digital revolution transformed the industry. [4]

Fujifilm’s Response

Like Kodak, Fujifilm continued to reap profits from film sales, invested in digital technologies and tried to diversify into new areas. At both firms, the employees in the profitable film division were in control and late to admit that the film business was a thing of the past. So, why the different outcomes?

Although the two companies shared similar assumptions and internal politics, the differentiating factor was in execution. What Fujifilm did was go one step further than simply shift to digital photography from analog. Instead, it leveraged its chemical expertise to pioneer new business fields. Under Shigetaka Komori, who became President in 2000 and CEO in 2003, Fujifilm underwent a bold and distinctly un-Japanese process of structural reform and aggressive acquisition. They looked at the fields to which its existing technology could be adapted and started acquiring companies that would complement their business. They moved into digital X-ray and endoscopes; they now have a 70% world market share of tac film, an essential component of all LCD screens.[4]

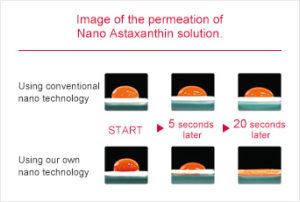

Another area it pursued was cosmetics (which they call “Life Science”), which was set up as a division in 2006. They found that the chemicals they developed over the years to prevent color in photographs from fading, could be used on skin too. Unknowingly, in their efforts to perfect film stock the researchers had been laying the groundwork for a skincare business. (Below shows nanoparticles of Astaxanthin, a red ingredient filled with beauty power, that Fujifilm formulated which became the basis of their skincare products.)

In 2007, Fujifilm launched their anti-aging skincare line ‘ASTALIFT’ which quickly gained popularity. In the following years they expanded to China, Southeast Asia, and Europe, while becoming one of Japan’s top-selling anti-aging skincare brands. [5]

Lessons from Kodak

In contrast to Fujifilm, who realized the need to develop in-house expertise in the new businesses, Kodak believed its core strength lay in its strong brand and marketing, and could simply partner or buy itself into new industries, such as chemicals and drugs. However, this approach proved unsuccessful as they realized without in-house expertise, they lacked the ability to effectively vet acquisition candidate, integrate companies it had purchased and negotiate profitable partnerships.

For example, when sales from film developing and printing were dwindling, some revenue could still be gained by installing kiosks to print digital photos. Whereas Fujifilm had its own system, Kodak needed to partner with another firm—and thus share the income. Moreover, when Fujifilm applied their kiosk technology to other businesses in its digital-imaging division, Kodak could not since it didn’t own the technology.

Conclusion

In an age where technological advances are occurring faster than ever, companies need to be more proactive in sensing and adapting to the changing times. Fujifilm’s example reminds us the importance of having in-house expertise and constantly looking into new technologies. It also teaches us that “execution” is just as critical as having the right “strategy”.

[727 words]

Sources:

[1] K.N.C (2012) Sharper focus. Available at: http://www.economist.com/blogs/schumpeter/2012/01/how-fujifilm-survived (Accessed: November 2016).

[2] L, B. (2013) Kodak moments just a memory as company exits bankruptcy. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-09-03/kodak-exits-bankruptcy-as-printer-without-photographs (Accessed: November 2016).

[3] Corporation, F. Fujifilm global. Available at: http://www.fujifilm.com/products/skincare/history/ (Accessed: November 2016).

[4] Monocle (2013) Renewal process – issue 60 – magazine. Available at: https://monocle.com/magazine/issues/60/renewal-process/ (Accessed: November 2016).

[5] Foundation, N.C. (2011) Fujifilm finds new life in cosmetics. Available at: http://www.nippon.com/en/features/c00511/ (Accessed: November 2016).

[Featured Images] Corporation, F. Photogenic beauty. Available at: http://astalift.com.bd/astalift/ (Accessed: November 2016).

This is great work, Hide. I did not realized Fujifilm was so diversified. I think Fujifilm also deserves credit for taking digital imaging more seriously than Kodak did. Indeed, some of their compact cameras are among the most respected on the market. Fujifilm deserves a lot of credit for identifying new fields (like cosmetics) where their legacy expertise (like dyes) allowed for competitive entry and not just increased R&D expenses.

Great post. I think Fujifilm is a great example of the risk as well as the opportunity in the digital revolution. Traditional businesses can lose their competitive advantage because of technological innovations and new emerging digital business models. However, these traditional businesses also hold a significant knowledge base and expertise that can be leveraged and utilized in other industries. Flexibility and adaptability to industry-wide changing conditions are the key factors that allowed Fujifilm to survive. Diversifying a company to new business fields and products can be complicated and require substantial investment, but it also reduces risks (much like diversifying a portfolio of stocks), and creates new opportunities for growth.

This is a truly fascinating post. I love the comparison of Kodak and Fujifilm. I agree that for a business facing a dramatic shift in technology, it must evolve to avoid extinction. Fujifilm’s strategy and execution were both very bold. From the point of view of leveraging its existing technologies and expertise, I see the logical paths Fujifilm took into medical devices and even cosmetics. I wonder how it was also able to evolve its operations to establish divisions that shared knowledge, technology, and resources, but faced such different customers.

What an unexpected diversification move! It’s amazing to see how FujiFilm has survived the digital onslaught by leveraging its internal research based assets to move into seemingly unrelated industries. In the case of FujiFilm, I believe digitization has meant an overhaul of its core customer promise and operating purpose. If I hadn’t read this post I would not have realized that FujiFilm has moved beyond “film” into cosmetics. I am inquisitive about how their organizational model and structure changed with diversification and whether photography would be their core focus going forward or not. It seems to me that given research and innovation are the anchor of their business model, they would eventually become a conglomerate of sorts for a wide range of products.