From “Visibility” to Prosperity

Fixing the broken promise of the digitally-connected farmer in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Agricultural supply chains in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are undergoing a digital transformation. As mobile networks have expanded across the continent, digital technologies have begun to enable value chain actors to trade and communicate across regions, utilize capital and labor more efficiently, and achieve greater scale in sales and procurement [1].

Success stories of “connected” farmers are touted widely by the international development community. Providing Ugandan maize farmers with accurate price information improved incomes by 15% through greater bargaining power at sale [2]. Farmers in northern Ghana have used an internet-based mobile platform to access new markets [3]. The Zambia National Farmers Union has used data visibility to offer mobile services for scheduling, monitoring and coordination of shipments to its members [4].

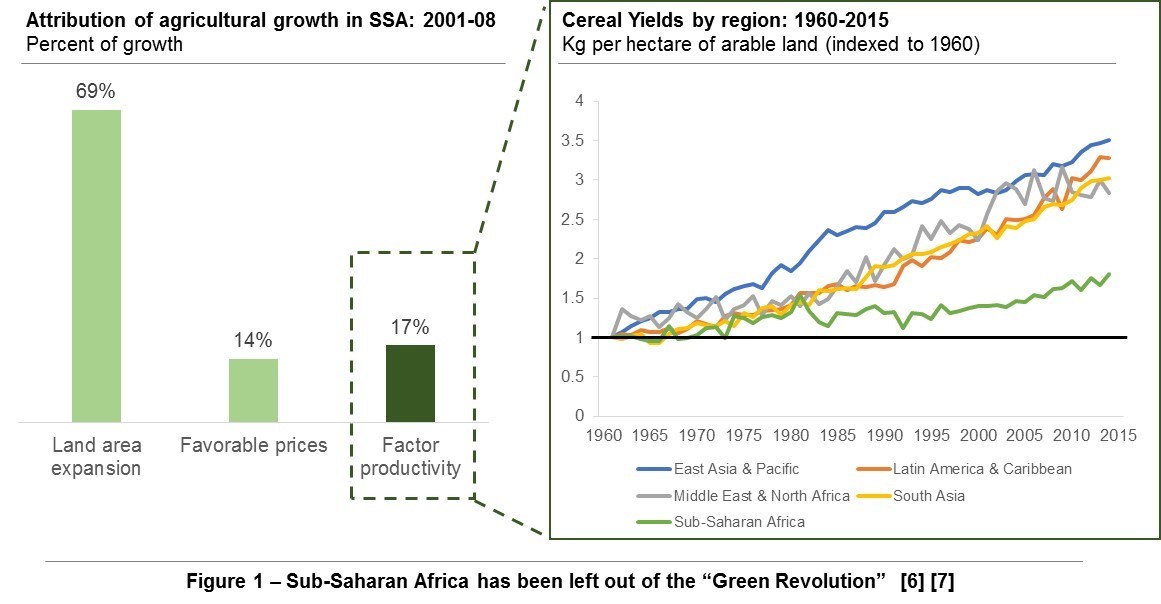

While the promise of digital remains alluring, it is less clear how it will ultimately influence outcomes for the poorest. Despite the gains in agriculture productivity brought about by the “Green Revolution” throughout much of the developing world, productivity improvements have contributed minimally to agricultural growth in SSA (Figure 1). The prospect of poor countries “leapfrogging” to greater levels of development by employing the latest technologies is often cited as a rationale for digital investment; however, Harvard development economist Calestous Juma warns that such leapfrogging may not result in inclusive growth for all [5]. The experiences of one company looking to digitize agricultural supply chains to benefit African farmers gives a clue as to why.

Virtual City: transforming food supply chains for global impact

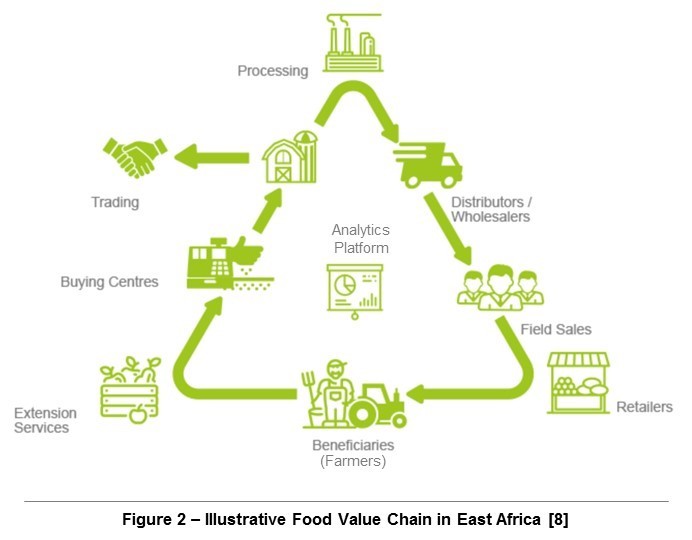

Virtual City exemplifies many of the opportunities and challenges in improving supply chains through digital. The Kenya-based company has developed a platform which allows supply chain actors to track the flow of agricultural commodities from farmer to retail with the stated mission of improving the well-being of farmers (Figure 2). To that end, the company has adopted a two-stage model. First, the company sells individual supply chain solutions targeted to each value chain actor: buying centers, processors, distributors, retailers. Second, the company uses value chain-wide data to deliver analytics to improve business decision-making and de-risk investment. In the near-term, the company is focused on sales capability to achieve regional scale. In the years to come, the company plans to expand across the continent and provide predictive analytics to generate further efficiencies across supply chains [9].

This approach, however, is unlikely to generate the promised gains for smallholder farmers.

Firstly, full participation is needed across disparate supply chain actors to create visibility. The complexity of managing multiple value propositions, go-to-market approaches, technical solutions has proved challenging for the company and has slowed adoption [10].

Secondly, visibility on its own tends to benefit more powerful actors, particularly foreign-owned corporations from countries like the United States bestowed with preferential trade agreements by African governments [11]. Poignantly, evidence from India suggests that the primary beneficiaries (in terms of the effective price paid or received for agricultural products ) of mobile-enabled purchasing platforms are sophisticated buyers, not farmers [12].

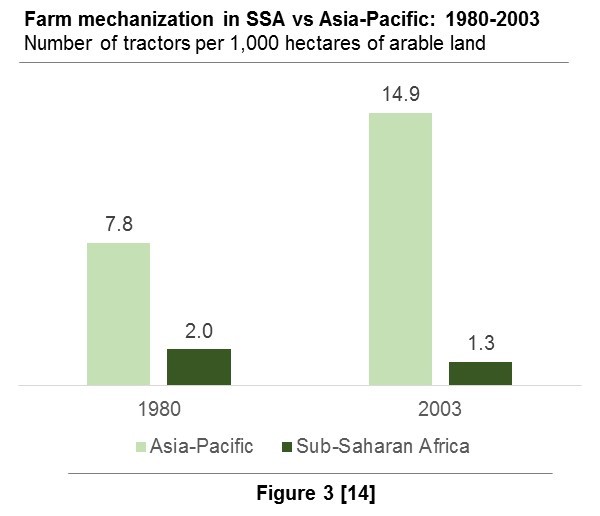

Thirdly, visibility on its own does little to address the underlying drivers of poor agricultural productivity – that farms are inefficient, undercapitalized, and too small to accommodate investment in irrigation or mechanization [13] (Figure 3).

Using digital to create income for farmers, not Western buyers

To better facilitate the digitization, Virtual City should refocus its selling efforts on influential stakeholders which can force immediate adoption of its platform across entire supply chains. For example, agricultural cooperatives, to which 7% of the African population reportedly belong [15], serve as regional aggregators for specific crops and thus have meaningful leverage over buyers. Such an approach will undoubtedly require a longer selling cycle but will help Virtual City remain targeted in its communications and product development activities.

Furthermore, Virtual City should develop interventions that specifically address the productivity barriers faced by smallholder farmers. For example, supply chain visibility is being used to facilitate credit access for farmers to purchase basic inputs like fertilizer and high-yield seeds [16]. Taking this idea a step further, digital supply chains can enable the creation of shared infrastructure models for smallholders to access capital goods (e.g., tractors, irrigation) previously available only to land-rich farmers. Digital technology facilitates such an intervention by enabling farming communities to pool credit and coordinate equipment sharing since downstream demand is now visible to cooperatives [17].

Looking forward

Clearly, opportunities exist for digital supply chains to transform the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa, not just corporations. What is less clear is whether the appetite exists to embrace such change. What kind of behavior change will be required of farmers and cooperatives? How might powerful corporations respond if farmers accumulate information and power? Will governments listen more to the needs of poor farmers or powerful corporations? Answers to these questions will be fundamental to whether the benefits of digitization will be shared by the poorest.

[799 words]

Sources:

[1] World Bank Group. 2016. “2016 World Development Report: Digital Dividends”. World Bank Group.

[2] Svensson, J., and D. Yanagizawa. 2009. “Getting Prices Right: The Impact of the Market Information Service in Uganda.” Journal of the European Economic Association 7 (2–3): 435–45.

[3] Egyir, I. S., R. al-Hassan, and J. K. Abakah. 2010. “The Effect of ICT-Based Market Information Services on the Performance of Agricultural Markets: Experiences from Ghana.” Unpublished draft report, University of Ghana, Legon.

[4] Zambia National Farmers’ Union (ZNFU). “The ZNFU Submissions on the Role of ICTs in National Development”, submitted to the Parliamentary Committee on Communications, Transport, Works and Supply. Published 4 Jan 2017.

[5] Juma, Calestous. “Leapfrogging Progress: The Misplaced Promise of Africa’s Mobile Revolution”, The Breakthrough Journal, No. 7. Published summer 2017.

[6] International Fund for Agricultural Development. 2016. “Rural Development Report 2016: Fostering Inclusive Rural Transformation”. Rome, Italy: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

[7] World Bank Development Indicators, accessed 14 November 2017.

[8] Virtual City website, accessed 14 November 2017 <http://www.virtualcity.co.ke/approach/> .

[9] Personal interviews with Virtual City management team (John Waibochi, Eric Mwiti, Catherine Irungo, Herbert Thuo, Dennis Gathage, Brian Ndunda) in Nairobi, Kenya, summer 2017.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Meltzer, Joshua P. “Deeping the United States-Africa trade and investment relationship”, Brookings. Published 28 January, 2016 < https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/deepening-the-united-states-africa-trade-and-investment-relationship/>.

[12] Banker, Mitra, Sambamurthy and Mitra. 2011. “The Effects of Digital Trading Platforms on Commodity Prices in Agricultural Supply Chains”. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 35(3): 599-611.

[13] Jayne, Thomas S., David Ameyaw. 2016. “Africa’s Emerging Agricultural Transformation: Evidence, Opportunities and Challenges”, Africa Agriculture Status Report 2016: Progress Towards Agriculture Transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa, Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

[14] “Investment in agricultural mechanization in Africa: Executive summary”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (NAO) and United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). FAO 2010.

[15] Develtere, Patrick, Ignace Pollet, Fredrick Wanyama. 2008. “Cooperating out of poverty: The renaissance of the African cooperative movement”, International Labour Office, World Bank Institute.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Personal interview with Baba Adongo, Deputy Country Director of TechnoServe in Accra, Ghana, 6 January 2017.

Thank you for the great analysis and commentary Justin. It’s interesting to see that only 17% of agricultural production growth came from productivity gains during the early 2000s. To answer your question on who of the farmers and the corporations will get the governments’ backing, I think that it is most likely to go farmers’ way as those voters are becoming more and more key for politicians. Indeed with urbanization and the urge in internet usage, voters in cities are becoming more and more demanding and harder to please than rural voters who have a narrower set of criteria for judging politicians such as their pro-agriculture policies.

Justin, thank you for writing this! It is interesting that there is a company that uses digitization to transform food supply chains in Sub-Saharan farms. Your recommendation makes sense, and I believe that it will help with the productivity barriers that farms are experiencing. However, I am slightly concerned in two areas. First, how much would it cost and how long would it take for influential stakeholders to equip the entire supply chain with Virtual City’s platform? Second, with full adoption, how much productivity gain would it bring to the farmers? Would it be large enough to compensation for the investments required to fully adopt the entire supply chain?

Thank you, Justin – this article does an excellent job of highlighting the more nuanced impacts of technological innovation. One question comes to mind here that seems important in understanding how to “transform the liveihoods of smallholder farmers in SSA, not just corporations,” as you importantly highlight. What is the root cause of the data shown in your first exhibit? Is this a result of physical farming conditions, or infrastructure considerations? The answer to this question will inform ways that digitization can be more effectively leveraged to improve productivity for farmers, and therefore actually provide gains for farmers.

It seems to me like some of the solutions needed have to do with scale creating access to capital intensive resources. Your examples of shared infrastructure (e.g. pooled credit and equipment sharing) highlight some ways I hadn’t thought about that digitization can enable communication to make these things possible.

You ask whether farmers, cooperatives, corporations, or governments will cooperate to make such improvements economically feasible. I actually am most interested in understanding whether there are economic gains to be generated by technology companies like Virtual City in focusing on this type of digital innovation. It seems to me that everyone in the supply chain would benefit from improved productivity and yields of smallholder farmers. My question is, is there a way to create a business model that captures this value?

Justin, this is extremely well articulated and really gets to the heart of the inefficiencies in agriculture in SSA.

There are a number of information transparency platforms for agriculture in the region (e.g., E-Soko, Precision for Agricultural Development, M-Farm). I think they have provided incremental gains in efficiency due to infrastructure constraints and lack of access to financial services for subsistence and small farmers. Farmers may understand the price that the market is buying their produce for, but they still cannot command fair prices from the middle men that come to their arms to buy their goods. This is because the farmers do not have the means to buy/rent vehicles and transport their own goods to the market, leaving them at the mercy of what middle men are willing to pay.

I second your emphasis on targeting cooperatives and aggregating supplies. There have been a lot of proven use cases of this model in India, where cooperatives successfully aggregate goods from farmers to sell to larger buyers. This also provides the benefit of improved ability to forecast demand and stabilized pricing. Only when the buyers are secured, can information transparency really start to benefit small farmers. I would also just add that this model can be adapted to other products beyond agriculture, like crafts, or clothing makers. Small business owners can also benefit from transparency of market information, aggregated goods, and improved access to financing and buyers through cooperatives.