From Chocolate Ice Cream to Deforestation in Borneo

How consumption of daily products destroys forest in Southeast Asia

It was another three-case day at HBS! I woke up at 7AM, brushed my teeth with Colgate toothpaste, showered with Dove shampoo and Lux soap, had a bowl of Kellogg cereal, put on Clinique moisturizer and Mac lipstick before heading to school. In less than an hour on an average day, I have used six products that contain palm oil. The list doesn’t stop there, palm oil is used in thousands of food & beverage, personal care and industrial items. Being one of the most versatile ingredient on Earth, palm oil is the world’s most produced and consumed traded vegetable oil, accounting for 38% of global vegetable oil consumption in 2014/15. [1]

85% of worldwide palm plantation is in Indonesia and Malaysia with total area of 14 million hectares. Emission due to palm oil deforestation and plantation account for 2%-9% of all tropical land use emissions from 2000 to 2010 [2]. Slash-and-burn practice in islands such as Sumatra and Borneo leads to severe haze crisis that impacted most of Southeast Asia countries annually and destroys biodiversity with endangered animals such as orangutan. In 2015, more than 28 million people in Indonesia alone were affected by the crisis; the haze caused more than 100,000 additional deaths. The total cost of this haze crisis to Indonesia economy alone was estimated between USD35-47B. [3]

In addition, peat soil which is commonly found in tropical forest of Southeast Asia contains an amount of carbon comparable to the carbon stored in the above ground vegetation in Amazon. If all this carbon from peat soil is released, the amount is equivalent to nine years of global fossil fuel use. [4]

Being the largest palm oil processor and trader in the world, controlling 45% of global palm oil trade [5], Wilmar faces significant risks from all participants of the ecosystem. This business is not sustainable for farmers when they suffer severe health consequences and deteriorate farming conditions. Governments of Malaysia and Indonesia can impose significant financial penalty and regulations to mitigate environmental and economy damages. Another major risk is potential boycott of their customers due to increasing awareness of destruction caused by palm oil business.

In December 2013, Wilmar launched their policy of “No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation Policy” [6]. Partnered with Unilever, this movement pushed many other big names such as P&G, McDonald’s, and Starbucks to join the zero-deforestation pledge. [7]

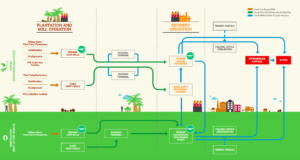

This policy applies not only to facilities and plantations that owned by Wilmar but also to all joint ventures and third party suppliers. Traceability is a big challenge in palm oil landscape given its high level of fragmentation and complexity. Within Malaysia and Indonesia, Wilmar has 44 owned upstream mills and 800-850 third party upstream mills.

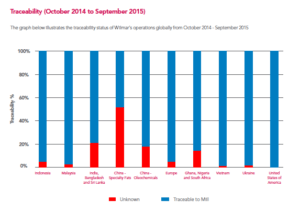

In January 2015, Wilmar is the first company to publish the list of known third party mill sources; by mid 2015, they had identified all direct mills supplying Wilmar operational facilities in Malaysia and Indonesia. Wilmar achieved more than 80% traceability in most countries that they operate in by September 2015. In addition, more than 80% of Wilmar’s own plantation are RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil) certified. [8]

Despite all these initiatives, Wilmar is still unable to prove that its suppliers are not responsible for accelerating rate of deforestation in Indonesia [9]. In fact, there are ongoing land grab claims and the haze crisis in 2015 was one of the worst air pollution in history of Southeast Asia. One pitfall here is the lack of enforcement in No Deforestation policy to its suppliers. Without a crystal clear guideline on consequences on non-compliance, effectiveness of the whole policy is questionable.

Deforestation is an issue at macro scale that I believe Wilmar can’t address by itself. A tight partnership with government, companies and NGOs, together with ongoing education and incentives to farmers are required to make any drastic change. The landmark soy moratorium to prevent Amazon deforestation offers a valuable lesson for palm oil industry. An unprecedented collaboration between soy traders, producers, and users were signed in 2006, with participation of Brazil government, main suppliers of agricultural loans and Brazilian Space Agency in 2008 has led to a spectacular drop in expansion through deforestation rate from 30% to 1% [10]. In May 2016, the moratorium was renewed indefinitely. [11]

Controlling half of total palm oil trade globally, Wilmar is in the position to drive changes in a product used by billions of people daily.

(735 words)

[1] World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), “Palm Oil Buyers Score Card 2016”, http://palmoilscorecard.panda.org/file/WWF_Palm_Oil_Scorecard_2016.pdf, accessed September 2016

[2] Union of Concerned Scientist, “Palm Oil and Global Warming”, http://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/legacy/assets/documents/global_warming/palm-oil-and-global-warming.pdf, accessed September 2016

[3] Wikipedia, “2015 Southeast Asian haze”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015_Southeast_Asian_haze#cite_note-27, accessed September 2016

[4] World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), “Palm Oil Buyers Score Card 2016”, http://palmoilscorecard.panda.org/file/WWF_Palm_Oil_Scorecard_2016.pdf, accessed September 2016

[5] The Guardian, “World’s largest palm oil trader criticised for lack of progress on deforestation”, January 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/jan/26/worlds-largest-palm-oil-trader-criticised-progress-deforestation-wilmar

[6] Wilmar’s website, “No Deforestation, No peat, No exploitation policy progress update”, December 2015, http://www.wilmar-international.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Wilmar-Policy-Progress-Report-Final.pdf

[7] [8] Bloomberg, “A Palm Oil King Develops a green conscience”, March 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-12/wilmar-chairman-pushes-palm-oil-industry-to-clean-up

[9] The Guardian, “World’s largest palm oil trader criticized for lack of progress on deforestation”, January 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/jan/26/worlds-largest-palm-oil-trader-criticised-progress-deforestation-wilmar

[10] Greenpeace.com, “The Amazon soya moratorium”, 2014, http://www.greenpeace.org/international/Global/international/code/2014/amazon/index.html

[11] Greenpeace.com, “Brazilian Soy Moratorium Renewed Indefinitely”, May 2016, http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/news/brazilian-soy-moratorium-renewed-indefinitely/

It has been proven that the palm oil industry is detrimental to natural ressources, but what is also a new subject of debate is the health impact of palm oil consumption. Indeed, several medical organisations worldwide have stated that they are significant negative side effects (such as heart disease) that are linked to the consumption of palm oil. Moreover, they are many available alternatives to palm oil to be used as an input for consumable goods but palm oil is just the cheaper option and hence the way to go for most companies. Knowing all this, do you think there is a justifiable argument for Governments to get engaged in the regulation of palm oil use (such as specific taxes or maximum threshold)?

Wow! It is fascinating how prevalent and impactful palm oil is, in Southeast Asia and beyond. This article is very well done.

While glad Wilmar and others are making a push for change, I agree the problem needs to be addressed by more parties. I’m not sure the region can wait for government, or for consumers to boycott hazes however, because we can see that by then the damage is already done. In response the the above comment regarding health concerns around palm oil — if we don’t use palm oil, there’ll be another substitute out there that, possibly with worse impact. I think the solution is to make palm oil harvesting and production earth-friendly and health-friendly (if the latter is possible).

Accordingly, one point I would add to the article would be to amplify consumer awareness around not just the haze, and the knowledge of slash-and-burn behind the haze, but of palm oil itself and its implications — and especially the brands that use palm oil heavily to pressure them to be more transparent about their practices. I was previously unaware of how many brands I use contain palm oil, and where exactly that palm oil is sourced as well as those company’s supply chain practices. Certainly, I would prefer to spend my dollar on the more responsible brand, but by the time I have researched every ingredient of all of my products, it may be too late!

Thanks for bringing awareness to this issue Van! I wasn’t aware how many products I use that contain palm oil. Rude awakening.

Are there regulators here? I know for a fact that there are NGOs that can provide metrics and/or a stamp of approval to Wilmar’s sustainability practices. My dad is a banana producer and has to be compliant with practices set forth by the Rainforest Alliance because Chiquita (his main customer) requires him to; it would seem that the Rainforest alliance could also have a critical role in regulating the palm oil industry. Check out their site!

http://www.rainforest-alliance.org/

Thanks for a great article, Van! I lived on Borneo for a year and witnessed this type of clear-cutting often. I agree that a combined effort is necessary to combat this – as you mentioned, partnerships with government, NGOs, and education initiatives. To that list, I might single out the coal and oil industries as well. In addition to palm oil manufacturers, the Borneo is full of coal/oil producers (most notably Chevron and Total). What made their dealings particularly controversial was that these were foreign companies with a lot of negative influence over the local governments (bribes, tax breaks, etc). While governments and NGOs try constantly to change the behavior of these companies, I think those coordinated efforts are tough with such powerful companies. To that end, I wonder if larger organizations such as the UN Environment Program or the National Government of Indonesia, should jump into the fray?

Van – thank you for the information! I didn’t realize Wilmar’s operations were changed so drastically. One interesting facet of the situation to consider would be cost structure implications – how has Wilmar’s bottom line been impacted? I realize many competitors are following suit with sustainable changes, but if one doesn’t and thus doesn’t have the negative consequences to their profitability in the short term, does that provide a short term competitive advantage? I find the transition to sustainable practices and its cost and competition implications to be a major factor in the decisions that companies have to make.

I’m fascinated because I never knew that palm oil specifically was such a strong driver of the farming habits and haze issues across South East Asia. I recall living in the area in the 2000s and going to elementary school every day wearing these haze masks. Not quite understanding at the time where the root cause was, I would only hear people blaming every other nation / island than themselves. The issue is actually so prevalent in people’s lives that it’s taken on a comic twist; Spotify Malaysia created a playlist called “Hazed & Confused” with song titles acting as social commentary, including “Smoke gets in your eyes” and “We didn’t start the fire”. I’m glad to hear that a major player in the industry is moving forward with more socially responsible sourcing practices, but also hope to hear more about government controls and fines. Do you think that the competitive nature of agriculture across the South Asian countries is causing governments to turn a blind eye in favor of their own farmers?

Great Article. For agri-businesses like Wilmar, any thorough attempt to combat emissions or deforestation needs to actively engage and educate Farmers in the Supply Chain. One particularly forward-thinking competitor is Olam International, a Nigerian-based agri-business who has launched programs aimed at educating it’s supplier and logistics providers on specific measures for reducing emissions and deforestation.