Ford’s Future in Great Britain Post-Brexit

Ford faces numerous challenges in managing its European and UK supply chain post-Brexit.

The global movement toward protectionist policies has serious implications for Ford Motor Company and its operations in the United Kingdom and Europe. Ford, as part of the automobile manufacturing sector, operates in one of the most targeted industries in a broad retreat from globalization where two-thirds of all new government trade policies since 2008 have been isolationist in nature.[1] Great Britain’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union is one of the most poignant examples of this widespread movement and the details of the plan for transition in 2019 are critical to Ford’s future business strategy in Europe and globally.

Ford is particularly vulnerable to the Brexit decisions because of its decentralized supply chain across Europe and its significant recent investments in manufacturing facilities in the UK. In the decade following 2000, Ford invested more than £800 million to convert its plant in Dagenham, England from building the Fiesta to its current role of designing and manufacturing diesel engines to supply other assembly plants.[2] By 2013, Dagenham accounted for over 50% of Ford’s global diesel engine production, even though Ford no longer assembles any vehicles in the UK.[3] In 2014, Ford completed an additional £475 million investment to add a green diesel production line that increased employment by 300 employees and added an additional 500,000 engine capacity, pushing annual production to well over one million engines.[4] Any changes to the existing trade policies will affect the profitability of the Dagenham plant and force Ford to make tough supply chain decisions regarding future production strategies.

There are several specific implications of the Brexit agreement that could make continued production for Ford in the UK financially unfeasible. Excessive paperwork associated with customs checks—as much as 20,000 separate declarations—would hamper export of engines to Germany and other countries.[5] Ford could also end up paying tens of millions of pounds each year for additional warehouses to create inventory buffers to protect against customs bottlenecks and Ford assembly plants might fail to meet Original Equipment Manufacturing (OEM) requirements which determine tariffs according to the percentage of vehicle components manufactured in Europe.[6] While the costs of Brexit are often associated with these customs issues, other considerations such as the ability to influence EU regulations, employee mobility through Europe, and bargaining power between the EU and other foreign markets are almost important concerns.[7]

In the short term, Ford has already raised prices of finished vehicles reimported into the UK to try to recoup costs related to the Brexit vote.[8] Ford also needs to engage in the Brexit conversation to shape the conversation where it can and to anticipate future policy changes elsewhere. By working with other auto manufacturers, Ford can draw the government’s attention to areas of concern and provide relevant economic data to strengthen the arguments for particular decisions. For example, Honda has lobbied the UK government to raise the quota of Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) companies to streamline custom approvals should the UK leave the EU custom zone (the UK has 600 AEO companies to Germany’s 5000).[9] While the EU might be reluctant to give Britain concessions in the terms of the Brexit agreement, there is an opportunity for Ford and other major automotive manufacturers to also work with the EU government to influence Brexit negotiations. The auto industry is an important employer and source of tax revenue across Europe and no country would want to see companies decide to consolidate outside the EU.

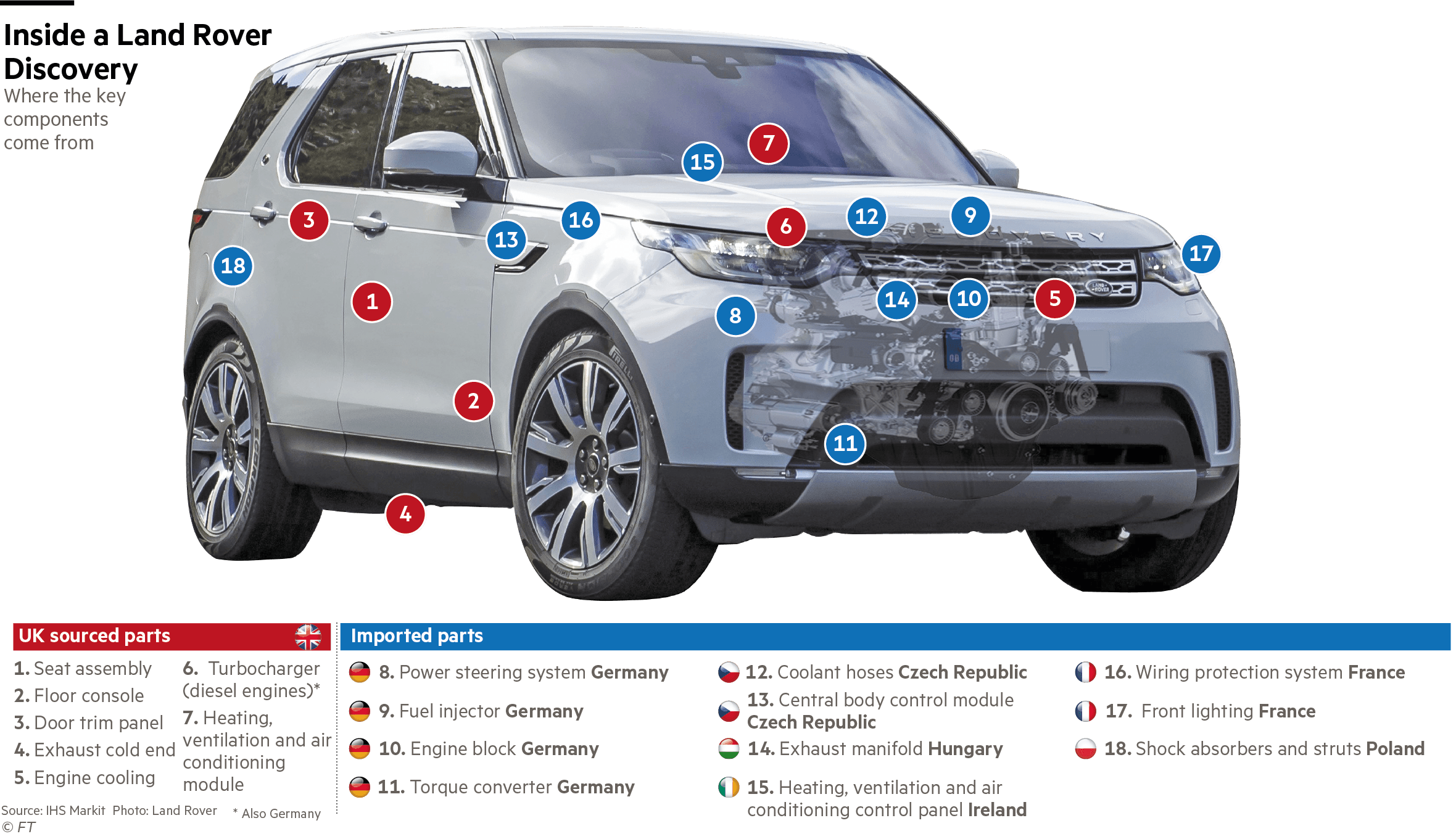

Figure 1. Inside a Land Rover Discovery [10]

In the medium term, Ford will need to restructure its supply chain to take into account the impacts of the Brexit agreement. Nissan and other manufacturers that assemble vehicles in the UK rather than elsewhere in the EU, have already decided to relocate suppliers to the UK to hedge against OEM risks (see Figure 1 for example of part production distribution).[11] Despite the expensive investments in its two remaining UK plants, Ford might need to consider consolidating suppliers near European assembly facilities. In fact, Ford has already proposed closing both facilities citing expectations to lose as much as £1 billion between 2016 and 2018 due to the Brexit decision.[12] In addition to raising prices, Ford should also seek economic incentives from the UK government to stay. Like Europe, Britain will want to retain Ford as a significant employer and source of tax revenue and might be willing to make favorable offers. Furthermore, Ford may be able to recoup some of its losses by selling to manufacturers trying to reconsolidate in Britain. None of these efforts will completely offset the impact of Brexit but they will help Ford continue to stay competitive through this uncertain economic period.

Considering the several decades that the UK has existed as a part of the EU, how closely will future trade relationships reflect the existing relationship? To what extent will Brexit drive companies like Ford to reverse their trends toward global supply chains?

(Word Count: 800)

[1] “Global Dynamics,” Global Trade Alert, November, 2017, http://www.globaltradealert.org/ global_dynamics, accessed November 2017.

[2] “Dagenham at 80,” Ford, May 13, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20100824105738/http:// www.ford.co.uk/AboutFord/News/CompanyNews/2009/Dagenham80, accessed November 2017.

[3,4] Jayne Scott, “Ford Continues High-Tech Engine Investment at Dagenham,” Ford, October 20, 2014, https://media.ford.com/content/fordmedia/feu/gb/en/news/2014/10/20/ford-continues-high-tech-engine-investment-at-dagenham-.html, accessed November 2017.

[5,6] Peter Campbell, “Carmakers fear Brexit customs checks will cost ‘tens of millions’,” Financial Times, November 9, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/4f6907d8-c58b-11e7-b2bb-322b2cb39656, accessed November 2017.

[7] “The UK Automotive Industry and the EU,” Financial Times, KPMG, April, 2014, https://www.smmt.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/SMMT-KPMG-EU-Report.pdf, accessed November 2017.

[8] Peter Campbell, “Ford warns of plant closures to combat $1bn Brexit blow,” Financial Times, July 28, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/5f20ead4-54c5-11e6-9664-e0bdc13c3bef, accessed November 2017.

[9] Peter Campbell, “Carmakers fear Brexit customs checks will cost ‘tens of millions’,” Financial Times, November 9, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/4f6907d8-c58b-11e7-b2bb-322b2cb39656, accessed November 2017.

[10,11] Peter Campbell and Michael Pooler, “Brexit triggers a great car parts race for UK auto industry,” Financial Times, July 30, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/b56d0936-6ae0-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa, accessed November 2017.

[12] Peter Campbell, “Ford warns of plant closures to combat $1bn Brexit blow,” Financial Times, July 28, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/4f6907d8-c58b-11e7-b2bb-322b2cb39656, accessed November 2017.

What an interesting read, Tom! I learned a lot more about Ford’s situation facing Brexit and I appreciate you connect the concepts we learnt in class to your writing (bottleneck, buffer, and supply chain ecosystem). I agree with your concern in the end. I would like to try to answer your first question and propose another key consideration for Ford.

1. How closely will future trade relationships reflect the existing relationship? From what I read, Ford has some estimates of loss and near-term remedy. According to Bloomberg, Ford estimates 600 million pounds annual loss just from Brexit, and it claims it lost $86 million in the past 3Q alone. (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-26/brexit-batters-ford-europe-as-tumult-sidelines-u-k-car-buyers). The automaker does have a measure of the loss, but the problem is how to reduce the level of harm and turnaround from the negative impact in global trade. Ford currently is currently pushing for a two-year transition period with UK where current trading conditions will stay in place. If it does work out, the policy will give the automaker more time.

2. My additional consider is that Ford’s supply chain does not just stop in the factory floor. It actually extends to the car financing division- an even larger market in terms of dollar value. Four in ten Ford cars sold in the UK rely on financing supplied by Ford’s financing arm. This arm- Ford Credit Europe, acts essentially like a bank offering loans to car buyers, and relies on its ability to operate throughout Europe on the UK’s membership of the EU and the so-called “passport” to operate throughout the bloc. (http://www.bbc.com/news/business-41935554). Brexit challenges Ford to rethink the supply chain from upstream in manufacturing to delivering to end user. Indeed, if car buyers lose the ability to finance and purchase the Ford cars, the key factor to success and customer promise will mean nothing.

Hi Yin! Thanks for your feedback! I especially like your second point about the financing division and agree that it will have even more significant impacts than the physical supply chain concerns I focused on. It will be interesting to see how Ford responds to overwhelming pressure to move from Britain to Europe while still retaining a large share of the valuable British auto market.

Great article Mr. President! Regarding your second question, I think Brexit will have a massive impact on the supply chains of domestic manufacturers, and while it may require significant upfront costs, the potential for billions of lost dollars to tariffs, alongside potential supply chain disruptions due to border customs could be all the incentive OEMs need to pull much of the manufacturing back to the states. This could also have positive implications in terms of turnaround time and lower inventory costs for these OEMs, furthering the potential benefit. Given the recent advancements in automation, questions do arise as to how much additional labor this will drive – regardless, the answer is certainly non-zero, which could be a boon for Detroit’s labor force.

An additional question I have is – will Brexit be a positive for US car makers in terms of sales to the UK? I am no expert on international trade deals, but if new tariffs between UK and the rest of the EU increase the cost of EU-manufactured vehicles, could this be a potential positive for US-based manufacturers selling into the UK?

Very interesting! As someone who has seen first-hand the complexities of a global OEM supply chain, this really resonated with me. I worked with an OEM that was having communication and recall process issues for their vehicles that were manufactured with parts from different countries. This post laid out well the complexities that will arise working cross-boarders.

Many of the US OEMs quickly expanded internationally with focus on the short-term cost savings. However, many of them did not fully grasp the different political climates and the collaboration required to operate effectively. To answer your first and second questions – I think it will ultimately depend on how well Ford can proactively work with the different governments to influence regulations in their favor and, in parallel, identify contingency plans for if they cannot. I think that events like Brexit, will potentially slow the global expansion of OEMs or at least force them to be more diligent when considering global expansion.

That’s a great write up Tom! There has been so much speculation about the true impact of Brexit, and this clearly shows that its ramifications are going to have a significant impact on companies.

Speaking about the impact on relations between the UK and the EU – there is certainly going to be a bitterness that will develop in the political class, which would most likely stem from the local populations expressing discontent arising from impact on jobs and industries. Economically, the rest of the EU largely stands to gain from Brexit with companies moving operations outside of the UK. While there would be organizations adopting the opposite route, they are projected to be the minority. Overall, there wouldn’t be too much impact on the region as a whole, the end result could be minor gains and minor losses for certain markets, most of the angst would come from the period of flux and uncertainty that is expected to arise in the near term.

Specifically for Ford, an optimistic view is that the firm would most likely create a hub for the EU and move operations outside of the UK considering the fact that the larger European market is great than UK alone. A more pessimistic view wherein the firm loses confidence in the direction things are going and believes more such policies might arise in future leading to more isolationism, they would be tempted to consolidate operations in their domestic market or countries similar to China that are highly favorable to outside investments and exports.

Thanks for a great paper, Tom!

Regarding your second question, my feeling is that an event like Brexit will lead companies to shift to a more localized supply chain. Your article does a great job of pointing out many of the real costs associated with Brexit – each one effectively makes it more challenging for Ford to operate in the UK. Beyond the real costs, there is also the challenge of managing the further uncertainty that is created. Companies’ supply chain investments are often long-term decisions and, as a result, the instability may make companies more reluctant to invest in global supply chains given the heightened risk.

With that said, a caveat: a recent article found that, while public sentiments around globalization and trade declined dramatically from 2005 to 2015, actual levels of globalization did not.[1] As a result, it’s possible that the actual impact of events such as Brexit on these investment decisions will be more muted.

—

[1] Pankaj Ghemawat, “Globalization in the Age of Trump,” Harvard Business Review 95 (July-August 2017): 115.

Wow! This article makes very tangible the intangible thought of a post-Brexit Great Britain and the effect it will have on daily lives. I can imagine that cars, already a high-ticket item, will become much more prohibitively expensive post-Brexit for the average British family in addition to a variety of other consumer goods. What is particularly interesting about the complexity you raised about Brexit’s impact on Ford is the context-specific implications of political isolationism. Quite simply, Great Britain may not have the space, number of workers, or natural resources in its Isles or population to support centralizing its car parts sourcing from inside Great Britain. This conundrum might look very different if faced by a larger country such as France, Germany, the US, or China which have much larger populations and natural resources from which to base resilience. Based on its strong historical legacy as a leader within the EU, I believe Great Britain will ultimately reach an agreement with the EU like the Schengen agreement between non-EU Switzerland and the EU which both satisfies political goals and economic goals for both parties and may mitigate many of the risks you outlined for Ford in your article.

Reading this article, I think the best Ford can do now is to negotiate with the British government on receiving economic incentives to stay in the United Kingdom. Unfortunately, the entity that is most affected by Brexit is the British people themselves who will have to pay in one form or another via their taxes going to subsidize companies like Ford to keep jobs in the UK or losing jobs and paying higher tariffs for cars manufactured in Europe. It seems sensible from Ford’s perspective to hedge their risks and start shifting their manufacturing outside the UK.

I wonder if there are any competitive advantages the UK has compared to other European countries in terms of manufacturing or sourcing parts. Are there any components of vehicles upstream that are most efficiently made in the UK? If the UK government is unable to provide economic incentives to auto manufacturers, which ones will remain, Ford or its competitors? This will be based on what other upstream components produced in the UK that make it favorable to stay there post-Brexit. I’m interested in the competitive environment of car manufacturers post-Brexit and their increased negotiation power with the UK government as other firms drop like flies and exit the country. I think that the competitors and their supply chains are an important consideration for Ford as it considers whether to stay or set up shop elsewhere.