Fonterra and it’s role in reducing New Zealand’s dairy industry emissions

Should the world’s largest dairy exporter should be doing more to reduce on-farm greenhouse gas emissions?

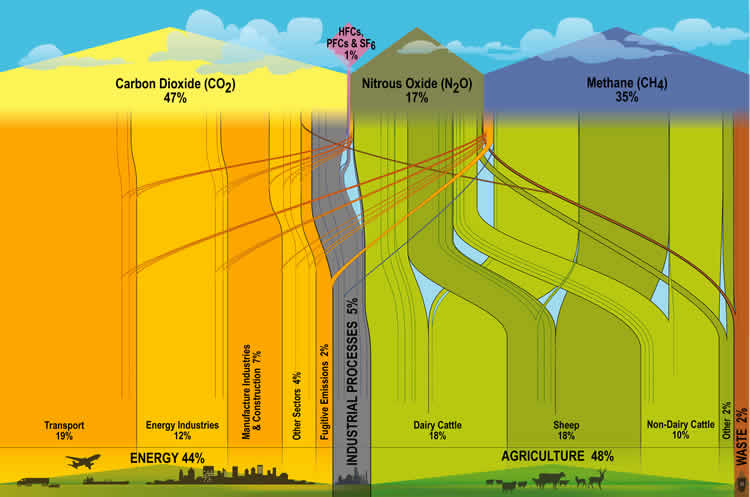

New Zealand is a country known for its pristine scenery and focus on environmental sustainability. Therefore, many people find it surprising that New Zealand’s per capita greenhouse gas emissions are actually higher than typical developed countries such as Japan and the United Kingdom [1]. Unlike many other countries, 49% of these emissions are created by agriculture, specifically methane and carbon dioxide from the dairy industry. In New Zealand, the word “dairy” is synonymous with Fonterra, a cooperative of 10,500 dairy farmers and the world’s largest exporter of dairy products [2]. Having grown up working on a farm which supplies Fonterra and spent a significant amount of time working with the company, I have chosen to focus on what Fonterra can and should do to reduce New Zealand greenhouse gas emissions.

Firstly, it is important to note that while Fonterra has a cooperative ownership structure, it should not be considered responsible for the emissions produced by dairy farmers during the production of milk. Fonterra actually has limited control over their farming practices and some argue the company has little responsibility to reduce on-farm emissions, instead saying this onus sits with the farmers themselves [3]. However, there are a number of reasons why Fonterra has been forced into action, most notably due to customers demanding higher environmental standards across the entire production chain. In addition, the New Zealand government is likely to remove agricultural emission exemptions from the domestic carbon trading scheme according to their most recent discussion document, something which will force farmers to bear the financial burden of any increases in emissions [4]. This article is divided into two parts; what Fonterra can do to reduce on-farm emissions and what Fonterra can do to reduce farm to customer emissions.

Around 85% of dairy related emissions originate on-farm, mainly caused by animal digestion and fertiliser application [5]. While many argue that Fonterra has an obligation to assist farmers in the reduction in these emissions, there is much debate around how best to do this. For example, creating regulation for farmers is unlikely to succeed given previous farmers response to similar moves in the past [6]. Almost all on-farm emissions are in the form of methane and nitrous oxide, produced in significant quantities by ruminant animals such as cows and the application of fertilisers. There are a number of potential ways to reduce these emissions including genetic improvements to animals, improved fertiliser application efficiency and modifying animal diet composition [7]. However, based on current technology, the costs of these changes are significant, mostly in the form of reduced milk production. For example, it is estimated that a 20% reduction in emissions could cause farm operating margins to decrease by 8 – 30%. Where many agree that Fonterra can play a key role is in reducing the magnitude of these costs through research and development of new technologies. Fonterra has already taken significant steps to do this, including funding an 18-month carbon emission footprint to accurate measure where on-farm emissions are originating [5]. However, given the high stakes, many argue the company should be doing more in this space.

Internally, Fonterra has made significant progress toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions. As with many food production companies, steam and energy are key inputs. In the past, much of this energy was generated using coal. Since 2003, the company has invested in energy conservation initiatives and moved toward natural gas and electricity for manufacturing facilities, resulting in a 14% reduction in total energy usage. Carbon dioxide emissions have declined by 320,000 tons since 2003 despite growing production [5]. The distribution chain is also responsible for emissions, mainly caused by trucks transporting milk from farms to factories. Here, Fonterra has invested in a technical fuel injection solution called GoClear, which can reduce truck emissions by 70 – 90% [5].

In summary, it is hard to dispute that Fonterra has done a significant amount to reduce its own carbon emissions. However, given the high stakes and significant public interest, the company should do more to assist farmers in reducing on-farm emissions also.

(675 words)

[1] Ministry for the Environment, “New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2014 Snapshot,” 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.mfe.govt.nz/publications/climate-change/new-zealands-greenhouse-gas-inventory-1990%E2%80%932014-snapshot. [Accessed November 2016].

[2] Fonterra, “Corporate Overview,” 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.fonterra.com/nz/en/About/Company+Overview.

[3] Department of Geography, Tourism and Environmental Planning, University of Waikato, “The political economy of a productivist,” Science Direct, vol. 32, pp. 266 – 279, 2006.

[4] N. Z. Government, “The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme Evaluation 2016,” [Online]. Available: http://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/Climate%20Change/ets-evaluation-report.pdf. [Accessed November 2016].

[5] Fonterra, “Fonterra Sustainability Fact Sheet – Climate Change,” [Online]. Available: https://www.fonterra.com/wps/wcm/connect/4c59510044921409b704f77cde4449c0/Fonterra+Climate.pdf?MOD=AJPERES. [Accessed November 2016].

[6] V. Small, “Warning to farmers: Better to move on emissions now than face major shock later,” [Online]. Available: http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/opinion/85509709/warning-to-farmers-better-to-move-on-emissions-now-than-face-major-shock-later. [Accessed November 2016].

[7] G. J. Doole, “Least-cost greenhouse gas mitigation on New Zealand dairy farms,” Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, pp. Volume 98, Issue 2, pp 235–251, 2014.

A very thought provoking post, COG – its great to see the Southern Hemisphere getting some airtime on these important issues. I agree with you that Fonterra has taken steps forward but the real question is have they done enough? Or more broadly, what is enough? As such a large company that is so important to the NZ economy (directly and indirectly), I don’t think this question should be posed lightly. Fonterra have a real opportunity to act as an architect and a beacon in driving not only NZ forward but also all agricultural companies globally, however they need to ensure that they do it profitably. Personally, I would like Fonterra to be more bold and look to make investments in more sustainable alternatives to dairy, such as soy or almond milk.

Cathal – Very interesting insight! I enjoyed exploring the contrast between a country perceived as being environmentally sustainable and a NZ company responsible for such significant carbon emissions. You clearly described the trade-offs the farmers are facing in balancing adaption steps with dairy output. Further, you clearly described that Fonterra is not doing enough now to mitigate their total emissions footprint. However, I’d like to see more on the steps you think Fonterra should take going forward. Are there other dairy cooperatives around the world taking effective measures? Are there other agricultural companies Fonterra can benchmark their performance against? Would it be beneficial for Fonterra to take a more active role in NZ farmer’s operation? For instance, Nestlé First Milk Sustainability Partnership is committed to improving sustainability through the entire dairy supply chain.

Cathal, I found this post quite interesting from a currency trading standpoint. Given New Zealand’s reliance upon dairy exports, the Fonterra data was always a huge indicator of the health of the NZ economy and any deviations from expectation would cause large fluctuations in the NZ dollar (aka the “Kiwi”). As a result, if there were an 8-30% decrease in operating margins for the dairy farmers (which, one would expect, would lead to lower output), I’d foresee quite extreme ramifications for the NZ macroeconomy and a severe weakening of the Kiwi. While this might be a good thing for some of the NZ exporters, it seems like an issue that would require significant structural change within NZ.

Well Done Cathal! Very interesting read. I feel as thought the conversation around where the responsibility lies regarding the farmer or Fonterra over reducing the GHG emissions at the farm level in an interesting one. The IKEA case showed us the power of an overwhelming #1 buyer and the influence that can be exerted at the top in order to change supplier behavior. Perhaps Fonterra has more influence in this conversation than what meets the eye. One way or another, my biggest question is how well is Fonterra diversified in Almond trees?!?!

Great post Cathal. My biggest concern here is the ability to reliably measure on-farm emissions at the source, which I believe is the first step towards emission reductions. An automobile very clearly has an exhaust pipe. A refinery has the flare. Acres of fertilized land populated by grazing livestock though? As an energy enthusiast, I have always appreciated the fact that the agriculture industry has its own challenges associated with GHG, but I always found it difficult to compare relative emission rates because of functional differences in the system value chains. I have a hard time wrapping my head around any potential mitigation systems that don’t require a massive adjustment to the traditional agricultural infrastructure.

A similar example of methane emissions that I always found perplexing is associated with hydroelectric power generation across dammed waterways. If you can believe it, the turbulent flow generated by releasing damed water through a hydroelectric turbine typically releases methane gases into the atmosphere that were previously created by the algae systems that occupy stagnant water sources such as lakes on the upstream side of dams. Here we are trying to produce clean, hydroelectric energy, yet we’re still somehow emitting harmful greenhouse gases.

Cathal, I really enjoyed reading this. Perhaps the most striking takeaway being that 48% of NZ’s emissions come form agriculture. I enjoyed how you dissected the problem – drawing stark contrast between on farm and farm to customer initiatives. Farm to customer appears to be the easiest to change – but the other side of it is much more challenging.

The most startling conclusion is that the on farm initiatives are minimal at best in reducing the methane footprint of animal digestion. It is troubling that currently the only initiatives (diet, genetic modification) are still tough to implement because of the high cost and impact on margins. Perhaps additional R&D investment grants within the local agricultural programs at NZ Universities could at least push the boundaries an what seems to be an impasse. Without innovation – this problem could be affected by regulation – but that clearly won’t hold as a sustainable long term solution. I think we need to look at it from a ver long term perspective 40-50 years in an attempt to innovate and begin to harness this issue with a sustainable solution.