Daryl Morey and The Houston Rockets: Building and Deploying Human Capital Through Digital Analysis

Information with real power comes in a variety of forms: both in the stereotypical form of databases and spreadsheets and analysts and predictive models, but also in the form of expertise and experience acquired only via a lifetime of playing and coaching the game.

The best organizations bring that all together.

– Daryl Morey, Grantland, 2011.

Since the invention of the game basketball teams have been run by “basketball guys.” As managers, these men judged players’ and teams’ performance through observation and decisions were made based on gut and experience.

Enter Daryl Morey. An MIT grad and former strategy consultant, Morey was not a “basketball guy.” However, he obsessed over two things: data and basketball. Morey became General Manager for the Houston Rockets in 2007 (think CEO). As GM for the Rockets, Morey has invested heavily in untried technology and has devoted his energies to gathering and analyzing large data sets.

Purists believe that basketball is a game of fluidity, collaboration and ingenuity, played by unpredictable and imperfect human beings: “Data and analytics have no place in such an inherently human thing!” Morey does not see the two inputs as binary, and contrary to popular belief he is not proclaiming a complete digital revolution in basketball.

Morey’s overarching thesis is that traditional methods of measuring performance were incomplete and misleading, consequently he has sought to use digital technology to collect more data AND to better understand what that data means. Morey seeks to use data to better enable the decisions that “basketball guys” make, providing new frameworks for evaluating performance.

How did we get here?

Traditional basketball stats were generic and often misleading. For example, players who compiled lots of points and rebounds were heralded without deeper thought as to how much those gaudy statistics translated to overall effectiveness. As new digital technologies emerged and exponential computing power became democratized, people like Morey and Billy Beane started paying attention. With Morey as GM, the Houston Rockets were the first team to install SportVU, an Israeli missile-tracking technology that uses tiny webcams installed in stadium rafters to record the x/y coordinates of each player thousands of times per game. Morey and his staff aggregate the immense data from SportVU into all types of statistics: how far a player runs, how efficiently they shoot from each spot on the court, how many times they dribble, etc. Every team in the NBA now uses SportVU, but few are as adept at making sense of it as Morey. The Rockets also use wearable devices such as embedded accelerometers to track player movement.

A New Basketball Business Model = new methods of evaluating player and team performance

The Rockets use the data as a lens through which to look at how a player performs. For example:

Player A averages 20 points and 10 rebounds per game, with a 50% shooting efficiency. While player B averages 16 points and 7 rebounds and makes 45% of his shots. Player A is significantly bigger and ostensibly a better athlete.

Which player would you take? Player A, right?

Advanced metrics might show you that player B is a more impactful contributor. What if player B’s true shooting percentage is higher than player A’s, his defensive efficiency superior, his rebound rate better?

Two Harvard PhD’s have also recently made their contribution to basketball analytics. Alexander Franks and Andrew Miller used player-tracking data and regression models to create a new metric for defensive evaluation.

For Morey and the Rockets, evaluation isn’t about raw totals, it’s about weighing the impact of each action a player takes.

New Operating Model: How Morey and others used digital tools to reimagine how teams and players should play

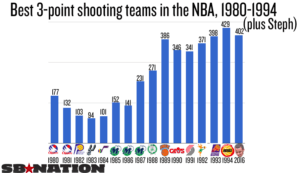

As new metrics pour in, managers, coaches and players have reimagined the way the game should be played on court. The 2015 NBA champion Golden State Warriors have embraced a “pace and space” strategy, spreading their players out and taking many shots in high efficiency areas (particularly corner 3-point shots). The Warriors’ Stephen Curry is an example of a player who has taken to heart information on the efficiency of a 3-pointer over a 2-pointer (albeit maybe not intentionally). As the 2016 NBA Most Valuable Player, Curry took more threes in a single season than any NBA team did from 1980-1994.

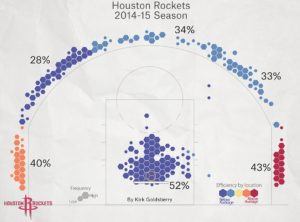

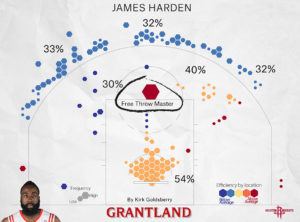

Morey has taken a more extreme approach. Using deep analysis to identify that the three most efficient shots were three-pointers (specifically from the corner), layups (near the basket), and free throws, Morey has steered his team to only take shots from those areas, and prohibiting “mid-range” shots (which have the lowest efficiency). Furthermore, Morey has built the team around the unique talents of James Harden, who’s natural style fits Morey’s strategy perfectly.

How has this worked out?

Overall, Morey’s teams have been competitive but not great. That said, almost all NBA teams now employ similar strategies to the Rockets (including the 2015 Champion Warriors).

Critics of Morey and the “nerds” point to the formulaic rigidity of analytics as improper for running a basketball team. Morey has been criticized for ignoring things like team chemistry when assembling a roster. He famously used a high draft pick on a player with anxiety disorder because the data said he was one of the best players in the draft (that player is now out of the NBA). Furthermore, in the 2016 NBA Finals the Cleveland Cavaliers beat the Golden State Warriors, despite the fact that the Warriors were superior in every advanced metric.

These results are not a referendum on the use of analytics, but just further proof that a great organization will not rely too heavily on either the art or the science. Statistical models are built on probabilities of voluminous events, and thus give great insight into what the best options for a basketball team (or business) are. That said, statistics cannot yet account for the vicissitudes of human performance or the intangibles of the game.

Daryl Morey does not think that he can build and coach basketball teams based purely on what the data tells him, but he does believe that traditional basketball minds have been looking at the game incorrectly.

Morey is doing what any good manager should do when their business meets digitization – he is asking questions. For Morey, it is not about the data, it’s about what the data means. He isn’t replacing the “basketball guys,” he is just making them smarter.

Endnotes

- CHARACTERIZING THE SPATIAL STRUCTURE OF DEFENSIVE SKILL IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL, Miller, Franks, Goldberry. The Annals of Applied Statistics 2015, Vol. 9, No. 1, 94–121 DOI: 10.1214/14-AOAS799 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2015

- http://grantland.com/features/moneyball-houston-rockets/

- Chris Ballard, Money Ballsy, SI.com; http://www.si.com/vault/2012/12/03/106260144/money-ballsy

- http://grantland.com/the-triangle/future-of-basketball-james-harden-daryl-morey-houston-rockets/

- Kirk Goldsberry, Mission Control; http://grantland.com/the-triangle/nba-playoffs-daryl-more-statistics-rockets/

Hi Rob,

I read this post with great interest. As a lifelong Warriors fan, I’ve been particularly interested (and pleased!) with their “pace and space” strategy and I appreciated the comparisons with how the Rockets implemented a more extreme strategy. You mention how ignoring team chemistry may have damaged the Rockets ability to perform, have you thought about how digital analysis might be applied to solve those problems? I know there is data about completed passes (http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-nba-players-no-one-passed-to-this-season/) but can this go even further to see which players passed to each other and then perhaps use this statistic to infer chemistry? Figuring out a digital way to assess teamwork would be broadly applicable in fields beyond basketball.

While I don’t think anyone has figured out an effective measure of team chemistry (the completed passes data to me is more basically a measure of good offense and may not correlate with strong chemistry), I don’t think it is out of the realm of possibility. I believe that more teams will start to use analyses like the one talked about in this Wall Street Journal article

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304392704576373641168929846

Digital analysis of intangibles will of course be met with resistance, but I agree with your intuition that it is certainly plausible – and probably fairly imminent.

Thanks for posting this Rob. I’m interested to know the implications of such technology on the overall style of the game……in your opinion how has the game evolved over the past 20 years? Has the emergence of this technology contributed to a more rapid change of tactics? Also if all teams now uses this technology on their own players as well as their opposition, why aren’t we seeing lower scoring games? Happy to speak with you in class about this rather than post responses. I also liked how you spoke about technology being complimentary rather than a substitute.

Interesting stuff Rob – I’ve really enjoyed following the rise of SportVU over the last five years or so. It’s pretty mind-blowing that you can translate a fluid game like basketball into readily-analyzable data on the position and movement of each player on the court. I’m most interested to see how analytics on the defensive side of the ball evolve over the next decade. It seems much less straightforward as to how analysts will assess the performance of a defensive player, given how much great defenses hinge on scheme and communication. I personally think teams may be undervaluing defensive players that don’t fit into a recognizable archetype, and may be an opportunity for smart GMs to nab some players on the cheap. The Thunder have been stashing flexible defensive players like Roberson and Grant with the thinking that offensive impact is easier to coach up than defensive proficiency. Perhaps one day undersized two-guards from the Patriot League will get the defensive acclaim they deserve.

Interesting post Rob. The stat about Steph Curry taking more threes last year than any team from 1980 through 1994 was particularly startling and shows how much the game has changed in two decades. I also like that you stressed that the art and science go hand in hand while forming a team. In addition to understanding what the most efficient shots should be, Morey knows that talent, above all, wins in the NBA and is willing to be flexible with his ideals to build a champion. While Harden is the perfect player for his strategy, the team recently pursued in free agency power forward Chris Bosh who repeatedly takes and makes more midrange “inefficient” shots than anyone in the league. However, as you mentioned, Morey knows that the additional skills and talent Bosh would have brought to the table would have made him a worthwhile investment. It will be interesting to track who Houston tries to pair with Harden in the years to come.

Great post Rob. I think sports is an ideal medium for the Internet of Things to enact a lot of change. I found your post particularly interesting because you highlighted the importance of how data is used by an organization and that it is not the end-all be-all answer. Data in sports is really meant to arm the managers, who, at the end of the day, still have to make decisions about people. Thinking back to that insane Golden State-Cleveland NBA Finals Game 7, I can’t help but think that data analytics still has a long way to go to surpass good old human motivation and talent. My question is how far will the digitization of sports take us and how long will it take for data analytics to simply outperform human decision making. Thanks for the insightful post!

I can’t wait until this trickles down to every level of all sports. It’s a shame that this kind of technology isn’t available to more players earlier in their careers.

One of my concerns for pro sports is that this can become more of a game theory challenge over time. For example, teams can predict where teams like the warriors hope to take higher probability shots, and adjust defense accordingly. I totally agree that this needs to be used in balance with strong strategies game-by-game.

Have they used this yet to infer defensive strength? I think this is an area with even worse data except for a few juicy stats like blocks and steals that are infrequent and poor indicators of overall effort and decreases of opponent offense.

Amazing post, Rob!

I first started think about sports analytics a couple years ago when I saw articles about soccer, such as:

http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/lionel-messi-is-impossible/

http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/messi-is-better-than-maradona-but-maybe-not-pele/

Before that, I sort of assumed this stuff only worked for baseball and that soccer was way too complex to analyze (actually, I thought it was even too complex to get the data, just like Mike felt about basketball).

I believe that the current order of “analyzeability” of mainstream sports is: baseball, basketball, then football / soccer.

Companies such as the ones you mentioned and OPTA sports (http://www.optasports.com/) are making this possible, but there is still a long way to go. With each new paper (such as http://www.sloansportsconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1457-Other-Sports.pdf), I get more confident in the power of sports analytics. However, I do agree that, at least for now, data is but a tool for the manager.

My question for you is: how much is this going to “trickle down” to college and high school basketball? Will 15-year-old players be evaluated using these new metrics someday? When?

Also, using these metrics, is it possible to “detect” doping? (e.g. if a player greatly increases metrics compared to his historical average).

Thanks!

Interesting article. I remember reading a lot about this as an undergrad looking at big data and its application in sports. It was early on when Morey was still implementing the idea of accurately tracking information and developing ways to use the data on the court. The articles I read mentioned how Shane Battier (a player for the Rockets) would get a packet of information on the behavior patterns of his opponents, particularly focused on his primary match up for the game. I remember thinking that data like this, while very useful for baseball as was seen with Moneyball, seemed less useful in more fluid sports like Basketball, Hockey, or Soccer. After reading more about how Battier would use the information my mind was largely changed. I think there are limits to the data, but understanding the tendencies of opponents and their overall behavior patterns can help you get a small leg up on them. I’m curious how you see information like this being used in the future and if players might shift toward receiving more regular in game feedback on their performance and that of their opponents.

Thanks for this fascinating post Rob. Really interesting to learn about the metrics that are changing the way all basketball players are judged.

My question after reading this post is how do the Rockets attempt to quantify the qualitative aspects of players, like being a good teammate? We often hear that the best teams win because the team is better than the sum of its parts and certain players are great leaders, or great for team chemistry. Are there any metrics that account for this qualitative aspect of team sports? How do the Rockets take less quantifiable aspects of players in to their evaluation of players and do you believe that they are undervaluing the importance of these qualitative aspects?

Coach Rob, this is a fascinating article. Given your amazingly analytical mind, it is no surprise that our intramural basketball team is still undefeated.

More so than in other team sports, basketball teams require players of extraordinary individual talent to win a championship. Other than the Detroit Pistons in 1989, 1990, and 2004, every NBA champion since 1980 (33 out of 36 years!!!) has been led by a player who won the NBA’s Most Valuable Player award at least once (Lakers – Abdul Jabbar / Magic / Shaq / Kobe; Celtics – Bird / Garnett; 76ers – Moses Malone; Bulls – Jordan; Rockets – Olajuwon; Spurs – Duncan; Heat – Lebron; Mavericks – Nowitizki; Warriors – Curry; Cavs – Lebron).

I think this explains why basketball data hounds, such as Morey, haven’t been as successful as their baseball counterparts. Marginal roster improvements matter more in baseball since every player gets the same amount of at bats, so there’s real value in optimizing much further down your roster. Transcendent basketball players such as Jordan and Lebron can dominate almost every play of a game. Even with the help of advanced data, it’s very hard to compete for a championship without having one of the world’s top 5 players.

Given that context, this data may be most useful in finding “system” players. A great example is the Spurs. Over the last decade plus, the Spurs built a distinct style of play around their Hall of Fame forward Tim Duncan. With their system in mind, the Spurs mined the data to find players, such as Danny Green and Kwahi Leonard, who would flourish in the system. Both players have become key contributors for the Spurs despite not being particularly exceptional on other teams earlier in their careers.