Climate change in Colombia – A water and energy dilemma

70% of electricity in Colombia is water-generated, making the country vulnerable to the effects of climate change. How does the sale of a State owned enterprise (SOE) factor into how Colombia better protects itself from El Niño phenomenon?

Context

Recent studies suggest Colombia is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change[1]. El Niño phenomenon is a climate pattern that describes the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean[2]. While El nino is a naturally occurring phenomenon, studies show the strength of this phenomenon has increased with the events of greenhouse warming[3]. In Colombia, the effect of El nino is a prolonged and extreme dry season. This is particularly disruptive given the relevance of water in many industries, especially energy generation. 70% of the energy produced in the country is hydroelectric energy[4]. In 2015, for example, 25,8% del total municipalities of the country suffered from water shortages[5], and the country came dangerously close to having systematic energy blackouts for the first time since the 1980s[6].

Through both the Energy and Mining Ministry and the Environment and Sustainable Development Ministry the government has developed mitigation plans for climate change as well as diversification of energy sources. Energy companies, however, have been placed on the spotlight by the public opinion, with many accusing them of poor strategic planning and administration with regards to modernization and efficiency efforts[7].

Colombia’s Electrical generation sector – the ISAGEN decision

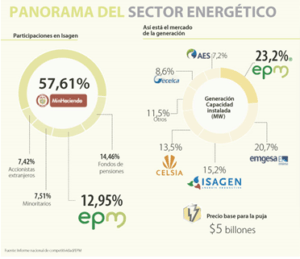

Given past failures, the electricity industry in Colombia is heavily regulated and vertically separated – companies have limits to their participation among the different parts of the value chain, be it generation, transmission, and distribution. Seven companies currently participate in the Energy Generation Sector, with precipitations ranging from 23% to 7%. Most of the companies are State Owned enterprises (SOE), although not 100% state owned[8]. In 2013, given the fiscal deficit the government faced due to falling oil prices and currency devaluation, the government put its 57% stake of ISAGEN, the third largest energy generation company in the country with a 15% share of the market, up for sale[9].

The move was heavily criticized from the political opposition, and there are many studies that suggest that utility companies have greater economic benefit to society as public rather than private companies[1]. One of the most interesting arguments I found, however, was that the sale of ISAGEN would impede it from continued investments towards the diversification of energy source from ISAGEN, which they currently (albeit on a small scale) invest in. The new stakeholders (Brookfields Assett Management) have little incentive to continue funding these ventures, when their impact on the companies’ bottom line is most likely negative[2].

I’d like to argue, however, that the privatization of ISAGEN might actually benefit my country from a climate change risk mitigation perspective. First of all, studies show that private utility companies are more effective at meeting regulators demands than their public counterparts[3]. Secondly, given the nature and high regulation of the Industry in Colombia, better financial results can mainly be obtained through a more efficient operation and use of the water resource and therefore a better use of current hydraulic resources. Given that Brookfield has more than 80 hydroelectric assets[4], it is reasonable to expect an increase in generation efficiency from the new owner since it will be aligned towards their profit maximization goals as well. Thirdly, a quick review of ISAGEN’s current efforts in preparing and mitigating for the effects of climate change are weak at best. While I do applaud the company for leading initiatives regarding information dissemination toward the Carbon Disclosure Project (CPD), the rest of their efforts basically lie on mapping and mitigating their carbon footprint[5], an effort that could be argued all companies must do.

I would recommend redirecting scrutiny not towards the sale of ISAGEN to a private player, but towards the actions that such companies must make in order to mitigate the risks their businesses intrinsically have given climate change. This pressure must not only come from citizens and government (they will suffer most from blackouts) but from shareholders as well. After all, without water, dams and turbines are quite useless themselves.

[1] https://www.hks.harvard.edu/hepg/Papers/Kwoka_Ownership_0295.pdf

[2] http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/economia/venta-de-isagen-comprometeria-expansion-del-sistema-ele-articulo-610164

[3] http://www.citylab.com/tech/2015/07/the-privatization-of-public-utilities-has-one-major-upside/398828/

[4] https://www.brookfield.com/en/Our-Firm/Global-Presence

[5] https://www.isagen.com.co/ResponsabilidadEmpresarial/proteccion-ambiental/cambio-climatico/

[1] http://www.upme.gov.co/Docs/Plan_Expansion/2015/Plan_GT_2014-2028.pdf

[2] http://nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/el-nino/

[3] http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v4/n2/full/nclimate2100.html

[4] https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Ambiente/Impactos%20economicos%20Cambio%20clim%C3%A1tico.pdf

[5] http://www.dinero.com/economia/articulo/que-prepara-cambio-climatico-para-colombia-2016/217400

[6] IBID

[7] http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/asi-fue-el-racionamiento-de-energia-en-1992-en-el-gobierno-de-cesar-gaviria/448643-3

[8] http://www.larepublica.co/superindustria-tambi%C3%A9n-condicionar%C3%A1-epm-en-la-puja-por-isagen_127266

[9] IBID

I recognize that a private buyer may instill more efficient operations in an effort to add rigor to the ISAGEN’s bottom line, however I may argue that the same logic may apply to lax treatment of the risk posed by el nino and the shifting climate landscape. If power gen players in Colombia truly need to diversify away from hydro-assets, the initial capital requirements to do so would be quite substantial. Additionally, although climate change may be increasing the frequency of el nino, the events are rather sporadic in regards to frequency (prior to 2015/16, the last el nino event was 1997/98). Depending on the private sector buyer’s time horizon, they may very well be inclined to not diversify away from hydro.

http://phys.org/news/2016-02-el-nino-global-warmingwhat.html