Cholera’s Comeback vs. ICG’s Supply Chain: A Matter of Life or Death

Rising ocean temperatures cause increased proliferation of the Cholera-causing bacteria, Vibrio cholerae, which is “influencing outbreaks on a worldwide scale” [1]. As these outbreaks increase so does the demand for the oral cholera vaccine (OCV). Despite the commitment of organizations like the International Coordinating Group (ICG), unpredictable vaccine demand continues to result in 2.9M cases and 95,000 deaths per year [2]. How can ICG effectively respond to the world’s increasing demand for OCV to prevent unnecessary deaths from a preventable disease?

Cholera’s Comeback

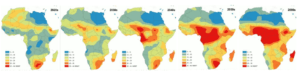

Cholera traces back to the 5th century BC, but as water sanitation has improved, cases have plummeted [3]. However, recently “cholera epidemics have been increasing in intensity, duration and frequency” [3]. Researchers have tied this increase to climate change: ocean warming and its effect on El Nino have paralleled a rise in cholera cases in endemic countries like Bangladesh & Peru [4]. Using this methodology, researchers have also built models predicting a future with higher cholera prevalence in areas not currently affected (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Warm colors represent new areas that are projected to see increased cholera prevalence

International Global Health Community Supply Chain & ICG

As cholera grows, the global health community is struggling to meet increasing vaccine demand of governments. The International Coordinating Group (ICG) is the primary organization coordinating vaccine access. This conglomeration of four global health partners – International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC), Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), UNICEF, and the World Health Organization (WHO) –forecasts demand, works with manufacturers to guarantee availability, and delivers supply to countries in need [5].

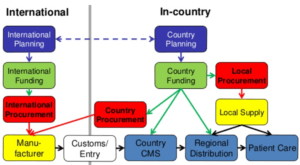

The ICG functions like a distributor but is also responsible for forecasting demand and informing production for manufacturers (see Figure 2). The increased number, severity, and geographies of cholera outbreaks make demand forecasting extremely challenging, resulting in vaccine shortages when the ICG underestimates demand. As cholera can take less than 18 hours from infection to death, a shortage can literally be the difference between life and death.

Figure 2: ICG is an international player in the global health supply chain

ICG’s Attempt to Keep Up

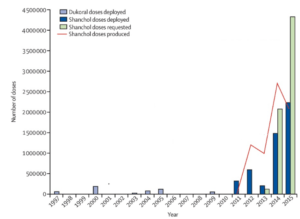

To address the growing demand of cholera vaccines, ICG created a supply chain buffer in 2014 by creating an oral cholera vaccine stockpile of 2 million doses [6 & 7]. However, in 2015 OCV demand exceeded supply by nearly 2.5 million resulting in an inadequate response to the cholera epidemic in Juba, South Sudan [8].

Figure 3: In 2015, doses of OCV requested exceeded doses produced by ~2.5M

To prevent another shortage, ICG has since focused upstream in its supply chain by strengthening manufacturer relationships. In the short-term, ICG has enabled tech transfers of the OCV technology to a second vaccine manufacturer, Eubiologics, and is continuing to work closely with this partner to ensure adequate supply [9]. In the long-term, ICG is lining up a bench of back-up vaccine manufacturers such as Va-Biotech and Incepta to more effectively respond to changes in demand [10]. ICG will have to invest considerable resources in supporting these manufacturers through pre-qualification, but in the long-term, their products can provide additional supply security.

Additionally, in the short-term ICG is also focusing on securing funding from GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance simply to continue the stockpile [10]. Current funding runs out in 2018, and the stockpile currently operates in a model where ICG pre-pays the manufacturer and assumes all inventory risk, including vaccine expirations [6 & 10]. In the long-term, ICG is considering transferring this risk to the manufacturers themselves and having them forecast demand and produce accordingly [10]. However, this approach has multiple risks with incentives still misaligned for for-profit manufacturers in global health, especially if producing at risk for epidemic-stricken countries [10].

Looking forward for ICG

Although ICG is taking effective steps to address its upstream supply chain – funding and manufacturers – I recommend they re-assess their demand forecasting and consider downstream supply chain as well. The 2014 recommendation of a 2M dose stockpile has not been revisited despite publication of higher-quality demand models as discussed in Figure 1. In the short-term, IFG should take these into account to provide more accurate estimates to their manufacturers.

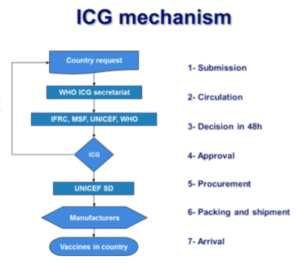

Additionally, IFC’s downstream supply chain has areas for improvement (see Figure 4). They strive for a 7 day lag time between approving vaccines requests and vaccines arriving in country; however, it currently takes 14.4 days [10]. This delay drastically influences overall demand because each day vaccines are not administered, more individuals are infected and spread the epidemic further. This ultimately requires more preventative vaccination and further increases demand. I would recommend assessing downstream causes of delay, particularly shipping times / patterns, to identify areas to cut down time.

Figure 4: ICG mechanism requires multiple touchpoints from request to in-country arrival

Conclusion

The future demand for OCV is uncertain but highly likely to increase as climate change continues to increase cholera’s prevalence. The strength of organizations like ICG’s supply chain and its strategic stockpile buffer not only symbolize business efficiency but in global health, also directly correlate to lives saved. Moving forward, its success will be determined by how quickly it can understand and adapt to changes in demand, and questions like “How can ICG balance spikes in demand and surplus inventory?” and “How will ICG incentivize manufacturers to share risk?” will be increasingly important.

Word count: 799

Citations:

1. Vezzulli, Luigi et al., “Climate influence on Vibrio” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (June 22, 2016) http://www.pnas.org/content/113/34/E5062.full

2. Ali, Mohammad et al., “Updated Global Burden of Cholera in Endemic Countries” PLoS Negl Trop Dis (June 2015) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4455997/

3. Harris, Jason et al., “Cholera” Lancet (June 2012) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3761070/

4. Rodo, Xavier et al., “ENSO and cholera” Proc Natl Acad Sci (Oct. 2002) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC130557/#B1

5. World Health Organization “International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision: Online Q&A” (Jun 2016) http://www.who.int/csr/disease/icg/qa/en/

6. Desai, Sachin et al., “A second affordable oral cholera vaccine” The Lancet Global Health (April 2016) http://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(16)00037-1/fulltext

7. Yen, Catherine et al., “The development of global vaccine stockpiles” Lancet Infect Dis. (March 2015) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712379/

8. Abubakar, Abdinasir et al., “The first use of the global oral cholera vaccine emergency stockpile” PLoS (Nov 2015) http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001901

9. Jerome Kim. Interview (May 29, 2017)

10. World Health Organization, “Annual Meeting: International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision for Cholera Control” (July 2016) http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255558/1/WHO-WHE-IHM-2017.10-eng.pdf?ua=1

Figures:

1. Wendel, JoAnna “Climate change predicted to worsen spread of Cholera” EOS (Jan. 2015) https://eos.org/articles/climate-change-predicted-worsen-spread-cholera

2. Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. Conference 2014 Report. Global Health Supply Chain

3. Desai, Sachin et al., “A second affordable oral cholera vaccine” The Lancet Global Health (April 2016) http://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(16)00037-1/fulltext

4. World Health Organization “International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision: Online Q&A” (Jun 2016) http://www.who.int/csr/disease/icg/qa/en/

This piece is very relevant given that cholera still continues to gain new ground in many parts of the world. Political conflicts and war-torn areas are places where vaccine supply chain performs the worst. In Yemen, for example, routes of exit and entry have been closed off due to the ongoing civil conflict. Due to the lack of water sanitation, almost half million people have contracted cholera and over 2000 kids have died to date. It is critical for multinational organizations to develop effective stockpiling capacity to address epidemics like this one in Yemen. A critical mass of children need to be vaccinated or re-vaccinated in order for the spread of cholera to be controlled. Funders like GAVI or the Global Alliance can address some of the financial shortfalls, but national governments should also be incentivized to devote more of their budgets to public health and vaccination programs.

I really enjoyed reading this post, and it is very timely. I found a 2014 publication by Desai et al. that emphasizes the role a sudden increase in Cholera (outbreak) can play in the collapse of already tenuous water and sanitation facilities in developing nations. It seems that over half of the deaths due to Cholera occur in children ages five and younger, which only further emphasizes the importance of solving the supply chain problems you have highlighted.

Interestingly, the efficacy of the oral vaccine seems to be lower in children, and the article posits that this may be due to factors including protein energy and micronutrient malnutrition, parasitic infections, and intestinal mucosal damage following environmental enteropathy. I bring this up because perhaps another issue that needs to be addressed in nations where climate change is likely to result in increased Cholera prevalence includes childhood nutrition to potentially increase the effectiveness of the OCV and thereby reduce the likelihood of Cholera’s spread.

If anyone is interested in more background reading on this topic, here is the article I referenced: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5396246/

This was a really interesting read. What I wondered while reading it is that, given the short time between infection and possible death, how does a company like ICG plan for areas that may not have a history of disease? For instance, do they proactively go into areas that may later be affected by cholera – or how would they respond to a proliferation of the disease in a region they’re not currently serving?

Additionally, it would be interesting to to see what type of research is ongoing to track the re-emergence of these diseases for forecasting purposes through ecological indicators.

Akanksha – Thanks for the post. Appreciated the real-life impact that a more efficient supply chain could have, to meet potential increases in the demand for vaccines due to climate change.

To your point on potential solutions to meet climate change’s impact — wonder if digitization could help in 2 ways:

1. Enhanced diagnostics on the current supply chain – To your point, we’d want to find downstream optimizations to minimize the lag until receipt of the vaccines. To address that, wonder if there are ways to attach sensors (and thereby get data) on the current shipping process? This would help us identify bottlenecks – including where the stalls are (where is ‘work in progress’ just sitting idly), which stations are ‘starved’ or ‘blocked’, any non-time-based breaks in the supply chain (e.g., temperature fluctuations that may destroy the vaccine’s potency), etc.

2. Prediction to re-route the supply chain – Based on the cholera prediction map that you highlight, wonder if there is a way for researchers to do 2 things: (1) identify reliable & accessible variables that predict at high certainty (if there are others beyond weather) and (2) get more granular demand prediction, down to 15-mile radiuses. Together, this would enable health organizations to start delivery before demand even surfaces.