Can Egypt Weather the Next Round of High Wheat Prices?

Back in 2011, Egypt was rocked by social protests partially caused by climate change-related weather patterns effecting the global wheat market. Has Egypt prepared for the likelihood of a return of high and volatile wheat prices?

Beginning in 2010, a wave of protests across the Arab World toppled governments that had previously appeared impenetrable. The causes of these protests would be too numerous to list and elevating a single cause as the cause would be impossible. However, social scientists have demonstrated that climate change played a significant role in stirring social demonstrations through producing high wheat prices caused by volatile weather patterns in Russia and the Ukraine.[1] Despite this recent history, the Egyptian government today is avoiding the challenges posed by climate change, including the threat of more unreliable global wheat supplies.

With nearly 100 million people and 4% arable land, Egypt is one of the most densely populated countries in the developing world for its population size.[2] Due in part to these variables, Egypt imports more wheat than any other country in the world, and its domestic production only meets half of the country’s demand for wheat. According to an Egyptian 2011 government report, the productivity of most agricultural products, including wheat, is expected to decline by 9-20% due to higher salinity (62) and higher risk of droughts.[3] Therefore, climate change will likely cause Egypt to become even more dependent on foreign wheat imports.

Due to population demands and a domestic industry crushed by corruption and state incompetence,[4] Egypt is turning even more to imports to meet its citizens’ demands for wheat. The Egyptian Ministry of Supply recently announced imports of 7 million tons of wheat in 2017-2018, compared to 5.6 million tons in 2016-17 and 4.4 million tons in 2015-2016.[5]

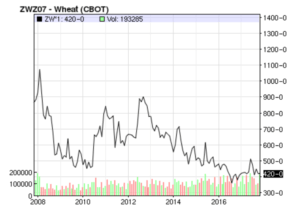

Egypt’s recent political turmoil has exacerbated economic challenges and the last few years have witnessed a growing unemployment rate coupled with a significant devaluing of the Egyptian pound. Egypt’s current administration has been blessed with low wheat prices (see Exhibit 1 below), but even with these low prices they nearly had a shortage in 2016.[6] The cost of the government’s wheat subsidy prior in 2010/2011 was 0.8% of Egypt’s GDP, and if prices returned to the highs of that period then they will be facing an even greater cost than at that time.[7]

Exhibit 1

Egypt’s imports of wheat are managed by the Ministry of Supply. The current government do not seem to have planned effectively for the likelihood of higher and more volatile wheat prices. In 2011, Egypt published a detailed “National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change,”[9] however the recommendations made in that document do not seem to have been adopted by the government that rose to power in 2013. The ambivalent attitude of the current administration to climate change mitigation is perhaps best demonstrated in their vague and generic contribution to the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change.[10]

I recommend that Egypt’s Ministry of Supply adopt the following steps:

- Diversify the sources of wheat imports. Nearly all of their wheat imports within the last year have originated in Russia, the Ukraine, or Romania.[11]

- Negotiate for long-term wheat contracts with large suppliers. Given uncertainty in Egypt’s currency value and wheat prices, the government could hedge a crisis by securing a long-term contract now while wheat prices are low.

- Re-commit to the 2011 “National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change,” particularly those actions related to increasing agricultural capacity and crop diversity.

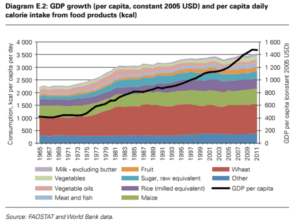

- Reduce government subsidies for wheat. They are distorting the market by hampering the development of alternatives and creating artificial demand for wheat. As one can see in Exhibit 2, these subsidies have prevented Egyptians from changing their food demands with global prices.

Exhibit 2

In closing, I would like to approach Egypt’s challenges with two solution-oriented lines of inquiry.

First, solving this issue will require more than just business knowhow or economic policy, but also political willpower and societal change. After all, Egypt is a subsidy-addicted country with a volatile and unstable recent political history. Are there any countries that have successfully shifted away from agricultural subsidies in similar circumstances in recent history?

Second, I think we need to acknowledge the occasionally contradictory requirements of mitigating climate change versus preventing climate change. In the developing world, mitigating the effects of climate change often entails adopting more of the carbon-intensive activities, like infrastructure development and manufacturing, that are causing climate change. For example, the Bank Information Center, an NGO that monitors DFIs, recently accused the World Bank, which has elsewhere funded climate mitigation, of pressuring Egypt to adopt policies that exacerbate climate change.[13] How can the international community support poorer countries to mitigate the risks to climate change that are specific to their country while still participating in global efforts to reduce carbon emissions? Do we need to pick a priority? (798 words)

[1] Lagi, Marco et al. “The Food Crisis and Political Instability in North Africa and the Middle East” (Aug. 15, 2011) Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1910031

[2] Eisa, Hesham, “Egyptian Development and Climate Change” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015) https://unfccc.int/files/adaptation/application/pdf/nwa_1.2_development_planning_and_climate_change_in_egypt.pdf

[3] The Egyptian Cabinet Information & Decision Support Center, “Egypt’s National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction” (Dec. 2011) http://www.climasouth.eu/docs/Adaptation011%20StrategyEgypt.pdf

[4] Knecht, Eric, “Egypt’s dirty wheat problem” Reuters (Mar. 15, 2016) http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/egypt-wheat-corruption/

[5] “Ministry of Supply announces details on new wheat” Almasry Alyoum (July 29, 2017) http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1169419

[6] Knecht, Eric, “Egypt’s dirty wheat problem” Reuters (Mar. 15, 2016) http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/egypt-wheat-corruption/

[7] McGill, Julian et al. “Egypt: Wheat Sector Review” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2015) http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4898e.pdf

[8] “Wheat: Latest Price and Chart for Wheat” Nasdaq (Nov. 15, 2017) http://www.nasdaq.com/markets/wheat.aspx?timeframe=10y

[9] The Egyptian Cabinet Information & Decision Support Center, “Egypt’s National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction” (Dec. 2011) http://www.climasouth.eu/docs/Adaptation011%20StrategyEgypt.pdf

[10] Arab Republic of Egypt “Egyptian Intended National Determined Contribution” (2015) http://www4.unfccc.int/ndcregistry/PublishedDocuments/Egypt%20First/Egyptian%20INDC.pdf

[11] Verdonk, Ron “Egypt: Grain and Feed Annual” USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (Mar. 15 2017) https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Grain%20and%20Feed%20Annual_Cairo_Egypt_3-15-2017.pdf

[12] McGill, Julian et al. “Egypt: Wheat Sector Review” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2015) http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4898e.pdf

[13] Mainhardt, Heike, “World Bank Development Policy Finance Props Up Fossil Fuels and Exacerbates Climate Change” Bank Information Center (January 2017) http://www.bankinformationcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Exec-Summary-1.11.17-2.pdf

This is a really difficult subject to tackle and honestly, I can’t think of a good case study of a country who has rolled back subsidies under similar conditions. The Egyptian government has not been able to offer true viable economic growth or opportunity to their citizens. In such a world, ripping away subsidies is the number one way to rile up politcal tensions (i.e. Sadat-era bread riots). The truth is though, the Egyptian government has no real incentive to change their policies because current policies keep them in power. They have been able to keep Egyptians dependent on subsidies and therefore dependent on the government. By controlling the food supply, they control the country and therefore, don’t have a reason to change. Food insecurity is almost a tool to maintain control. The key for the government is maintaining the right level of insecurity: make people dependent on you just enough to get by, but don’t make them too insecure or they might try to topple you. That said, the government is busy always putting out fires. Any small fluctuations become an ordeal.

Egyptian leaders need to decide if they are in this for the long game. If Al-Sisi is interested in maintaining power in the long term, he has to think about policy change. Otherwise, he’s always threading a very fine line between stability and political upheaval. I don’t see a world where Egypt becomes completely food independent. They will always need to import wheat, but they have to think about policies like you mentioned (diversifying sources, buying futures, etc.) that allow the price to remain as stable as possible, so they can start to think about longer term changes if the goal is to maintain political control.

Christina, I agree completely with your analysis. In my experience though, after meeting with various ministers of the Egyptian government back in 2012, the current policies are more an accident of history and a reflection of low political willpower than a piece of a nefarious plan.

Egypt’s reliance on wheat imports to feed its population is definitely a cause for concern, and climate change in an already arid part of the world is sure to exacerbate these issues. However, I wonder whether it is in the interest of the government, or Egyptians, to reduce the current wheat subsidy or shift to other products internally. While it certainly makes sense for Egypt to diversify its sources of wheat in order to reduce the chances of a shortage, the subsidy seems like one of the ways in which the Egyptian government can actually avoid the unrest of 2010 / 2011. If the Egyptian government increased its supply sources and locked in long-term wheat contracts in a low-price environment, it could mitigate much of the risk of another shortage without potentially destabilizing the country.

I agree that subsidies discourage further exploration of alternative food staples in Egypt, but unless Egypt invests in crops with lower water usage, aren’t water shortages fueled by damming and disputes upriver on the Nile (i.e., Sudan) an even greater cause for concern? In that scenario, it would seem that Egypt should solidify its relationships with a large number of foreign crop importers in order to protect against a scenario where Egypt lacks the water to farm its remaining arable land.

Thanks, Ben. That is really great analysis and you’ve posed a couple great questions. On the first question of why subsidies are problematic, part of the answer is that subsidies discourage exploration of alternative food staples, but there are many other reasons too. One other major reason is that the way the subsidies are managed are ripe for fraud, so only a portion of the benefit of the subsidies flows down to the people actually eating the bread. I don’t know the answer to your second question – I expect that water shortages may be a greater cause of concern as you’ve suggested. Egyptians are very concerned about Ethiopia building a Nile dam that would reduce the water flow to Egypt.

Thank you Eric for this great article that clearly shows the challenges that climate change poses in an unstable, government dependent and corrupted environment.

I wonder whether one solution to the problem of bringing more Wheat to the Egyptians could be a stronger presence/ collaboration of the private sector. As I understand from your article, and from the review . “Egypt: Wheat Sector Review” from McGill, Julian et al.(http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4898e.pdf), roughly half of the wheat imports are done by different agencies of the Government and the other half by private entities. However, there appears to be a huge difference in the efficiency of the supply chains, the one employed by the government being much more inefficient.

For instance, the review points out 3 areas that could be improved by a stronger private presence:

1)The government relies on call to tender processes to buy wheat; however, it usually does so with a very short notice, thus driving the prices up as the tenders will have to assume higher costs of transportation to comply. If privates companies were do that job instead, I am certain that they would be able to plan ahead and do a better job.

2)The government relies on a basic shona storage system to store wheat on land. That system is outdated, poorly maintained, and is estimated to contribute to 10-20% of wheat losses due to impurities. Silos storage system are more adequate and the government should turn towards those.

3)Government storage facilities are not operated in an efficient way, due to lower than required throughput. Giving control of those facilities to private sector would improve their efficiency as those companies would not only import wheat but other commodities, creating overall efficiencies.

Thank you, Jonathan, for that additional analysis. I read that review, but couldn’t fit in the word count, so I’m glad you’ve added it here! The past 15 years of Egyptian history have demonstrated that cronies in the government can limit the benefits of privatization by ensuring their buddies control the newly “private” businesses. So, I’m skeptical of how handing things over the “private sector” would immediately improve results. Despite that skepticism, privatization would be a step in the right direction.

Super interesting observation on the impact of climate change on social unrest – many have made similar connections between climate change, poor agriculture productivity, and the Syrian civil war [1].

The most salient contrast I see to the situation in Egypt — where farmers are the ones enjoying subsidies – is what many land-rich countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have gone through post-independence: government-controlled marketing boards, which have monopolies over domestic purchasing of specific agricultural goods, systematically pay below-market prices to farmers, extracting value to be used for big development projects and subsidies to the urban-industrial sector [2]. Some countries have gradually liberalized and devolved power to smaller political units like states (e.g., Nigeria), but I’m not sure there is a good playbook for building political will to take away a subsidy people have come to rely on, especially when those people form a powerful political block (e.g., corn and sugar farmers in the United States). That said, it looks like Egypt has recently slashed its wheat subsidies to try to fight corruption (although it is still subsidizing the retail price of bread for end-consumers) – time will tell what kind of impact this might have [3][4]. Realistically, I’d expect that farmers will respond to shifting production away from low-priced wheat to more profitable cash crops, potentially exacerbating Egypt’s food security problems.

Balancing mitigation and adaptation is an even tougher question – I don’t think it’s possible to choose just one. On one hand, it would be hypocritical for Western nations to demand poor countries to choose to cleanest path to industrialization while they themselves failed to do so. On the other hand, if the entire world consumed as much energy per capita with the same carbon intensity as the United States, no amount of adaptation will prevent truly catastrophic environmental impact. The most exciting mechanisms I’ve seen are based on making . Generalist multilateral structures like the Green Climate Fund have failed to deliver on their promises because due to lack of accountability, inconsistent commitment (Donald Trump has called the GCF a scheme to redistribute wealth from rich to poor countries [5]), and clarity of purpose; however, more focused bilateral arrangements delivering targeted technology transfer like the U.S.-India Clean Energy Finance (USICEF) initiative seem promising [6]. An additional challenge here is intellectual property rights, as Western companies are reticent to share latest technologies freely without compensation to the very same low-wage countries that compete with them at home and abroad. Creative policy, trade negotiations, and some moral leadership in the corporate world could have a real role to play.

Sources:

[1] Recent paper connected climate change to the Syrian Civil War: http://www.pnas.org/content/112/11/3241.abstract

[2] On the origins and functioning of state marketing boards in Nigeria: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03056248508703647

[3] Quick overview of Egypt’s wheat reform program: https://www.reuters.com/article/ozabs-uk-egypt-wheat-idAFKBN19X1WW-OZABS

My goodness, what a phenomenal post! Thank you for that thoughtful response to both of my questions. I was unaware of the examples in Sub-Saharan Africa that you mentioned – I’ll have to do more research there.

Eric, thank you for connecting the dots between climate change and political unrest. In America, we’re often blind to the tertiary effects climate change is bound to have in developing economies. Setting aside cost for a moment, this could be a perfect application for Indigo’s Winter Wheat that we learned about in an earlier case. According to Indigo’s website, Winter Wheat “demonstrates an average yield improvement of 15.7% in expected conditions and 8.3% across all conditions in the water-stressed target region of Kansas” [1]. More broadly, Egypt may want to consider the use of GMOs to increase their crop yields.

On the other hand, GMOs alone may not be the key. In addition to the development of climate-adapted seed varieties, some scientists are arguing for a switch from industrial agriculture to “ecological agriculture”, which replaces chemical fertilizers with compost and manure. Ecological agriculture practices have already helped farmers in western Africa boost soil fertility and ability to retain water [2].

I would love to discuss further soon!

[1] https://www.indigoag.com/pages/news/press-release-indigo-wheat

[2]http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2012/04/heat_resistant_seeds_ecological_agriculture_growing_food_after_climate_change_.html