CHIPKO: Story of your food. Source to consumption.

The king said:

“You foolish village women, do you know what these forest bear?

Resin, timber, and therefore foreign exchange!”

The women answered:

“Yes, we know. What do the forests bear?

Soil, water, and pure air.”

-The tree hugging women

The problem:

The story of our food is the story of humanity. Nothing binds us to our roots on a daily basis as self-evidently as food does. But that story has become incredibly complex and muddy today. Traceability of high environmental impact foods is critical in determining their true cost of consumption. Foods grown, typically in the tropics of the world (Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina, Central America, China, India, etc.) have been severely leveraging environmental debt made possible by a non existent accountability structure and an unapparent near-future socio-economic impact. The west has barely paid its fair share of this debt by smokescreening it as free market economics, but what it does not seem to comprehend is currency exchange valuations can never account for ecological extraction. The consumption of resources required to keep up with demand has acutely taxed these environmental hotspots (just google palm oil), and that consumption has only grown – exponentially at that. The sad part is, growers are usually the least valued assets of this value stream.

According to WWF’s Palm Oil Buyers Scorecard report, companies like P&G(0.463Million Tonnes consumed 2018), BNSF(0.42MT), PepsiCo(0.506MT), Ferrero(0.204MT), Nestle(0.425MT), Unilever(1.03MT), AAK AB(1.361MT) etc. have pledged to execute sustainable procurement and supply chain policies.

Let’s hold them accountable. Let’s be vigilant. Let technology and the tools she provides empower us and keep us honest.

Risks and costs:

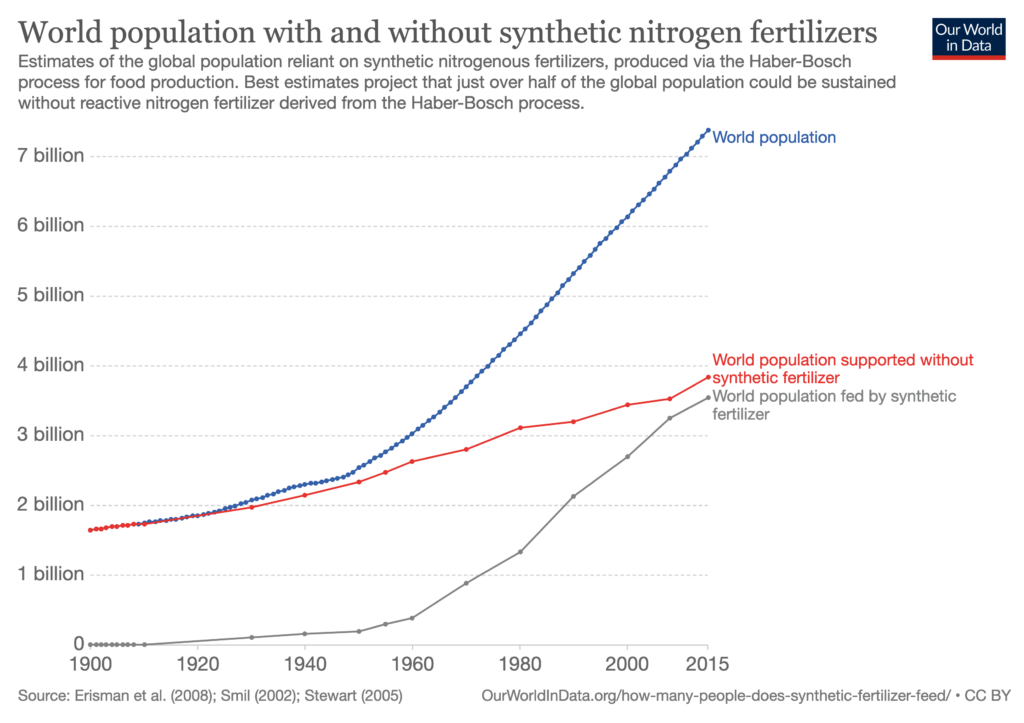

Practicing sustainable farming at scale will make or break the possibility of long-term peaceful existence of the human species as evidenced by the 04MAR2020’s TED talk by Allan Savory. Techniques like no-till, regeneration, crop-diversity, etc. have shown continued improvement in bio markers used in sustainable soil management. Land use changes, involving mechanization, over-exploitation of water resources and expansion of irrigated areas, intensive cultivation, and agricultural abandonment in mountain areas, have resulted in a very advanced state of land degradation or, in dry-land regions, in desertification.

Estimates based on specific types of land and regions across the world have been used to compute global figures; these add up to US$42 billion in annual income lost to land degradation and desertification. This figure has been subsequently inflation-adjusted to US$64 billion. Between 2010 and 2050, as a result of expected changes in population and income levels, the environmental effects of the food system could increase by 50–90% in the absence of technological changes and dedicated mitigation measures, reaching levels that are beyond the planetary boundaries that define a safe operating space for humanity.

Encroaching cash crops like cocoa, coffee, tea, banana, grape, saffron, vanilla, etc. that by nature are sensitive to their respective changes in environment, usually grow in the most pristine regions of the world that would otherwise have been ecological hotspots. It becomes all the more critical to sustainably farm in such regions and such crop. The supply chains of these products are inherently carbon intensive due to their non-local production-consumption cycles. Transparency of assets, input consumption, minimizing hand-offs between producers and consumers, sustainable land management practices, have all led to organizations like the rainforest-alliance to act as middlemen in the cycle of trust, and yet the loss of tropical evergreens has only accelerated.

Other nationally grown and consumed foods like corn, soy, wheat, potatoes, millet, etc. face a drastically different set of challenges. Mono cropping, glyphosate poisoning, soil degradation, and increased synthetic growth inputs to name a few.

Data and Transparency:

The dwindling public trust in certifying bodies like the USDA, rainforest-alliance, EU organic, etc. are a result of inefficiencies in their compliance and auditing processes. Most of these bodies are severely understaffed and lack the testing equipment necessary to conduct tests at scale. A framework like ROC which Patagonia, Navitas organics, and others, have invested in kick starting standardized sustainable practices for certifying the cotton and superfoods used to produce their merchandise, focus not only on the key quality markers of the end product, but hones in on the three pillars of sustainability: Soil health, Animal Welfare and Social Fairness, but is yet to define how these pillars will be reliably measured and demonstrate whether the framework can be scaled operationally. Moreover, frameworks like these leverage existing certifications as a baseline for new applicants. These organizations; for-profit or non-profit act as mediators between the growers and consumers, inherently relying on third parties for testing and auditing to keep up with increasing demand. The common denominator is that decision makers in the supply chain place value on these products purely as commodities and at the whim of market futures, undervaluing the incredible wealth of data that went into obtaining the certification.

Market: wherever end-to-end supply chain traceability adds value or is critical; a few examples are:

- Speciality Growers and Restaurants:

- Health care and corporate kitchens:

- Chocolatiers:

- Biogenics manufacturers:

- Wines and liquor:

- Luxury foods:

Bringing digestible data to consumers: Trust in data not certs

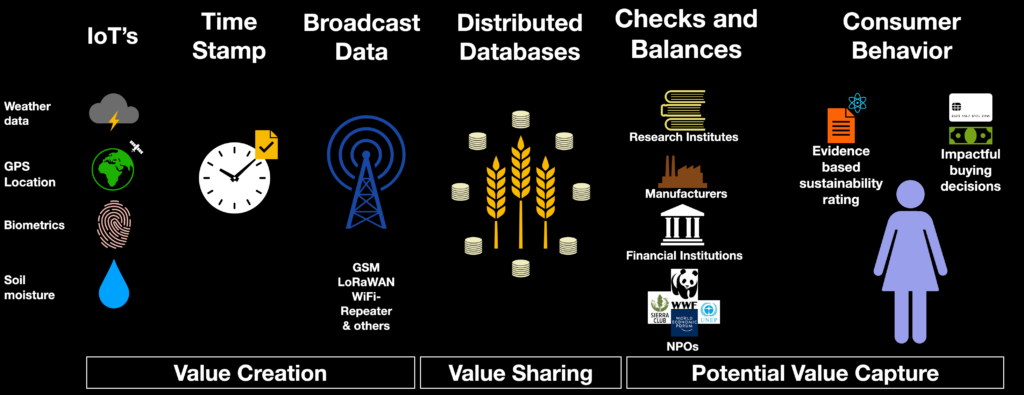

It is the nature of certificates to rely on certifying bodies. Certifying and rating agencies compete among themselves and are motivated to demonstrate their relevance by, upholding high standards and maximizing number of certifications issued; the two of which usually conflict with each other. In such a scenario, shared, untampered, machine generated data, openly shared with peers on a linked ledger for cross validation before being printed onto a tamper-proof label is a simple solution to generate direct value for the grower. The question Chipko endevors to answer is how can these vast arrays of datasets be meaningfully condensed for the consumer to encourage a purchase without diluting the trust in a faceless supply system.

Solution:

Monitor inputs. Share outputs. Validate results. Capture value.

The cost of sensing, IoT hardware and data storage have dropped drastically in the past decade. A plethora of open source solutions are now available for collecting, broadcasting and storing meaningful, reliable, encrypted data. Chipko aims to leverage existing infrastructure and open source hardware devices to cheaply collect data from each level of supply chain by biometric authentication without the need to collect or reveal sensitive data by applying AI models to recognize patterns in every transaction throughout the supply chain starting with land and resource utilization. Additional auditable data like fair pay to involved individuals in the chain will only make underlying processes just.

Competitors:

Firms working in farm data collection and suggestive farm input controls: onesoil.ai, mesur.io, CropX, SWIIM, Mavrx, EarthSense

Firms working in supply chain transparency: Bext360 (coffee), RipeIO

Differentiator:

Chipko will tell a story about your food (for now! but really the human experience). Chipko will establish trust devoid of private data and ensure institutional honesty at the most fundamental levels. We will strive to make technology as foolproof as possible by keeping it and the data open. We will love the faceless men and women who make our lives possible. Everyday.

The name chipko comes from the chipko movement. Chipko means: to stick together. Read more about it at: https://fore.yale.edu/World-Religions/Hinduism/Engaged-Projects/Chipko-Movement