GameStop the Ride, I Wanna Get Off

GameStop has been thrust unceremoniously into the 21st century, and it is very grumpy about it.

Founded in 1984 under the banner Babbage’s by two HBS alumni, GameStop rode the wave of video game popularity, initially specializing in sales of Atari and Nintendo games and equipment, which it later expanded to include all the major consoles and brands. The company as we know it today came about as the result of a cascade of roll-ups and acquisitions and mergers, including Funco, Barnes & Noble, EB Games, NeoStar Retail Group, Software Etc., Game Informer, and the original banner itself.

The company’s modern strategy could charitably be described as a ‘trade-in cycle’, which the company itself calls the “Circle of Life.” The model begins before games are even released, with employees incentivized to push pre-orders of games – where the customer would pay a ‘deposit’ on the game (~$10), and in return the store would guarantee the customer would receive one of the first shipments. In some cases, GameStop would partner with the game publisher to offer exclusive content, such as in-game collectibles, in order to incentivize pre-orders. For a brick-and-mortar retailer, the benefits of pre-orders can’t be overstated – it means extremely low working capital and high turns with no risk. This also enables the second and most important leg of GameStop’s strategy: used game trade-ins. The company would heavily advertise trade-ins, and offer cash at a 10% discount, or store credit at ‘full value’; however, the ‘full value’ of many used games could be as low as a couple dollars, even if they retailed for $60 several months prior. The company would then ‘refurbish’ the games (essentially just repack them in shrink wrap) and mark them back up for 5-10x their trade-in value. They then sell these same games back to the people trading in for store credit, revolving the stock like an over-priced Redbox.

For a while, this strategy was highly effective. Before online retail improved distribution and prior to the digital download revolution, GameStop was generally the only/best option for same-day gratification. Although websites like eBay and Amazon provided alternative points of sale, there were usually long buy/sell lead times, which were inconvenient for customers looking to clear their old games and make room for new ones. And with internet connections still catching up to the size of games, it could take days to download a single game.

GameStop has, however, utterly failed to adapt to a changing marketplace. They appear to be hemmed in on all sides: with the advent of Valve’s Steam platform for PC, GameStop doubled down on consoles; with the advent of Xbox, Playstation, and Nintendo online marketplaces becoming more popular and efficient, GameStop turned to mobile phones; but even those sales have been lackluster. Amazon offers new games that are delivered on the same day they are available in stores, and for the same price. Publishers are happy to disintermediate the retailer, particularly to tamp down on used games sales, for which they receive no share in the profit. Accordingly, since November 2013, GameStop’s stock price has declined over 70%, and shows no signs of stopping.

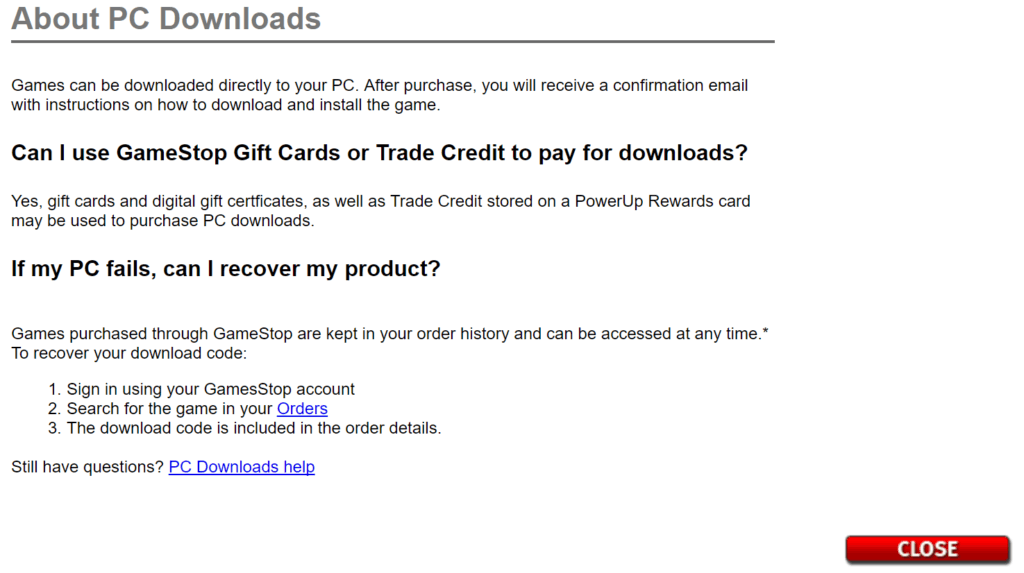

Instead of adapting, GameStop appears to be trying to extract as much cash from its current strategy as possible, at which point it will, presumably, liquidate inventory and close. That’s the only plausible explanation for the level of strategic paralysis they’ve exhibited. The ‘Circle of Life’ program mentioned above appears to be aimed at just this strategy: stores are now assigned quotas they must meet along four dimensions: 1) pre-orders, 2) reward card sign-ups, 3) used game sales, and 4) trade-ins. That is all as a % of total sales, which means that stores are disincentivized to sell new games – for every new game they sell, they will need to sell more used games, or risk firing or store closure. Games website Kotaku reports employees openly lying to customers about inventory or prices and turning away sales of new consoles so they don’t have to take the revenue ‘hit’. Meanwhile, they have stubbornly refused to invest in digital platforms or systems. See below for an example of a page from their antiquated PC Downloads section:

The company has shown no signs of adopting a new strategy, and with employee incentives in place that do real harm to the top-line, GameStop is standing in front of the tidal wave of the future with its eyes shut, humming, fingers in ears.

Gamestop is one of the most depressing places you can shop. Their pushy salespeople clearly want to be anywhere else and their stores are now cluttered with tchotchkes that have more to do with movies and TV shows than video games. That said, there are still a lot of people who don’t have the internet speeds (or patience) required for digital downloads. PC gaming leads in this space since computers don’t come with disc drives anymore, but most consumers still buy physical discs for console games.

Gamestop is clearly a dying brand and it is unlikely that they could win in the digital space. Is there anything wrong with extracting cash prior to liquidation?

Thanks a lot for this. Growing up, we had a storefront in the local mall that seemed to endlessly change it’s name between Babbages and GameStop until it was permanently GameStop. As kids we always assumed the two were in some kind of endless tussle and we all were loyal to Babbages – never knew they were the same thing!

Indeed, the vast number of promotions and product-pushing efforts they do at checkout suggest a business trying to really extract every bit of value they can before losing the customer. With the increasing pattern of direct digital downloads – and very little advantage to buying games at GameStop vs any large retailer – Walmart, etc. – it is difficult to envision a successful future for GameStop along the current trajectory and model.

I had no idea GameStop was once owned by Barnes & Noble at one point. I always knew they made a lot of their money on resales but I didn’t know they had established such an antagonistic relationship with video game producers. Although they’ve failed to make meaningful inroads into the digital marketplace, I’m guessing those producers weren’t too willing to partner up with them as the market shifted, which probably exacerbated their difficulties. Given these producers see margins jump by $10 when games are downloads and the digital market essentially eliminates any type of resale market, I wonder what options, if any, GameStop has going forward. It’s tough to see what kind of value they can add.