Freebird: Using data to get you out of a jam and onto a plane

Flight cancelled? You can still get to that wedding with Freebird.

We’ve all been there before.

Lined up in front of the gate agent, exasperated after deplaning, totally unsatisfied with a $10 food voucher. Other airlines’ flights are still taking off with empty seats, and the next flight on your airline is slowly filling up, one seat at a time, as the people ahead of you in line get their tickets. If you’re an average traveler and you really need to get somewhere, you have no recourse. You have to wait in line, break the bank for a new ticket, or just give up and cancel your trip.

After an experience like this stranded HBS student Ethan Bernstein and his classmates in Park City, Utah, Bernstein set out on a one-way entrepreneurial journey to solve last-minute flight delays and cancellations for good. Forgoing a second year at HBS, he partnered with an MIT researcher studying machine learning and launched Freebird.

So what was the big idea?

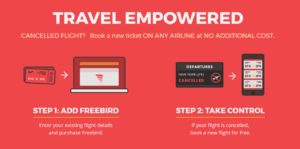

Using statistical analysis and predictive algorithms to forecast risk, Freebird promises to immediately buy a new itinerary on any airline (!!!) for any traveler who purchased the Freebird service and faced a last-minute cancellation or delay (in excess of four hours). By connecting into airline data systems, Freebird is able to notify passengers immediately via text message as soon as a disruption occurs – often before the airline makes an announcement and notifies other passengers of the disruption. With just three clicks, travelers can get a new seat, avoid the stress of lines, and maybe even get some buffalo wings to go as they walk to the gate of their new flight.

So isn’t that just like travel insurance?

Not really. For decades, airlines have of course built their own models to forecast demand for individual flights, as well as the likelihood and cost of delays or cancellations. They use these models to forecast revenues and manage costs, but they don’t really use the data to inform the price of their travel insurance products. On top of this, when you tick that travel insurance box at checkout, you’re really insuring the cost of your trip, not your trip itself. But that just doesn’t cut it when you really need to get to your best friend’s wedding. In that case, you’re less worried about the cost of the trip; you need to prevent a bride- or groomzilla rampage and spare yourself having to tell them you can’t make the ceremony. That’s where Freebird comes in.

Alright, so how does it work?

Using historical flight-level cancellation and delay data in combination with the historical cost of last-minute bookings, Freebird has built the foundation of a risk model that assesses the probability-adjusted cost of selling the company’s guarantee to any passenger. The aim, of course, is to sell the Freebird guarantee to enough passengers on lower-risk flights to more-than-cover the cost of rebooking customers with cancelled or delayed itineraries.

The company is still testing its early value capture strategies. For now, Freebird  offers an annual subscription or charges a one-time fee of $19 per one-way and $34 per round trip. The company website indicates these prices are part of a “launch promotion,” and suggests variable pricing is coming. A concern with these non-variable pricing structures would obviously be that a subscriber who flies the Chicago to New York shuttle every week in the winter may end up requiring more payouts than they’re worth. Similarly, a single-use traveler may require substantial acquisition costs and still present a relatively high likelihood of payout. For the existing models to work — or even just work well enough to keep some of their investors’ cash in the coffers — Freebird will need a broad enough base of customers to achieve the required levels of cross-subsidization.

offers an annual subscription or charges a one-time fee of $19 per one-way and $34 per round trip. The company website indicates these prices are part of a “launch promotion,” and suggests variable pricing is coming. A concern with these non-variable pricing structures would obviously be that a subscriber who flies the Chicago to New York shuttle every week in the winter may end up requiring more payouts than they’re worth. Similarly, a single-use traveler may require substantial acquisition costs and still present a relatively high likelihood of payout. For the existing models to work — or even just work well enough to keep some of their investors’ cash in the coffers — Freebird will need a broad enough base of customers to achieve the required levels of cross-subsidization.

Still, one can easily imagine a nice runway for growth as the startup’s risk models and pricing improve. For example, Freebird could improve its risk calculations by incorporating in-year weather patterns, estimating last-minute empty seat inventory across other airlines, and integrating data fields that specify causes of delay (e.g., a maintenance delay last winter may not need to be factored in this year). With this data, the company could then roll out sophisticated variable pricing that adjusts subscription or a la carte prices for different fare classes, cancellation risk levels, and estimated empty seat counts for last-minute rebooking.

What does the future for the company look like?

The company’s progress to date and vision for the future have earned a fair bit of praise from the likes of Forbes, Bloomberg, and travel media company Skift, but the company certainly faces some important challenges.

First and perhaps foremost, distribution is not an easy nut to crack here. Freebird is currently only available as a standalone purchase on getfreebird.com. Travelers aren’t used to booking their ticket and then subsequently thinking about adding on a service like Freebird’s on a completely different site.

First and perhaps foremost, distribution is not an easy nut to crack here. Freebird is currently only available as a standalone purchase on getfreebird.com. Travelers aren’t used to booking their ticket and then subsequently thinking about adding on a service like Freebird’s on a completely different site.

Second, the data problems will continue to be central to the company’s success. What data should be included in the risk model? Which parameters should the predictive risk algorithm evaluate, and how should each parameter be weighted? Are there thresholds of excess capacity on alternative flights that should determine whether Freebird even offers its service on a specific itinerary? And the list goes on.

Fly with Freebird

Next time you really need to get somewhere, consider buying Freebird after you buy your flights. Instead of letting a silly maintenance issue or a delay with the inbound plane ruin your trip, take power back into your own hands. Fly with Freebird.

Thank you for sharing this article, Adam. I met Freebird’s founder at an E-Club event last year and it was great to hear his story and how the company is growing post-HBS. As you point out, there might be some issues with the risk assessment model in adverse selection – people flying in the winter months between snowy cities when delays and cancellations are very likely to occur are also more likely to buy this insurance product.

If Freebird is now a stand-alone product and is only available via a different website than the one people use to book their tickets, how should they manage their Go-To-Market strategy? Would the business model work if they never integrate it with the airline ticket aggregator websites such as Kayak or Skyscanner? Do you think they should offer some revenue-sharing with the aggregators or the airlines directly so that they get featured? Would be great to hear your thoughts!

Cool post.

Are there any hidden variables here that are difficult to account for in the model? People sometimes talk about the increase in severe weather over the last 10-15 years? I really don’t have the historical experience to tell whether this is true, but are there large scale changes in the historical data set that Freebird might not see but could create huge gaps in their risk model going forward?

Second, is there any tail risk (especially in the early stages) that can bankrupt this company/destroy their ability to deliver on their customer value proposition? I’m guessing that people book this sort of experience all trying to fly a route from Boston to Denver in the dead of winter. On the travel day, a huge winter storm shuts down the airport and literally no flights get out. What does Freebird do in such a situation?

Thanks for the post – there are so many opportunities in the airline industry but mostly through ancillary services like this one and not necessarily at the airlines. I think an interesting expansion strategy for them may be to try partnering with an airline GDS (like Sabre or Amadeus) to (1) gain access to more data and (2) more seamlessly link to the airline websites. The risks here though are that the airlines don’t want a third party provider allowing customers to rebook onto other airlines and / or it gets lost in a clunky bureaucratic infrastructure.