Electronic Arts: Game On

Amidst the tide of rapidly advancing hardware, software, and internet technologies, companies in the video game industry must constantly evolve to stay competitive. Electronic Arts Inc. (EA), one of largest game software development and publishing companies in the world, is currently experiencing both incredible highs and lows as it transforms its business model to capitalize on emerging opportunities and succeed in a shifting landscape.

New modes of competition, interaction, and engagement

The shift of gaming to online and mobile has been every bit as transformative for the industry as the move from the arcade to the den and TV room. With the advent of 4G/LTE communication networks, expanded wireless LAN and Wi-Fi coverage, and ultra high-speed home internet connections, gaming experiences have become more connected and social than ever before.

Low-latency connections have led to the rise of new classes of games rooted in persistent online worlds and multiplayer experiences, rather than single-player stories. Led first by massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) and online first-person shooters, recent years have seen the rise of the multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) and battle royale (BR) games. Although these genres exhibit diverse gameplay styles, the most successful releases feature large social components and robust gameplay mechanics that support intense in-game competition. Together, these features foster the growth and development of committed, vibrant communities who keep returning to the same game worlds for long periods of time.

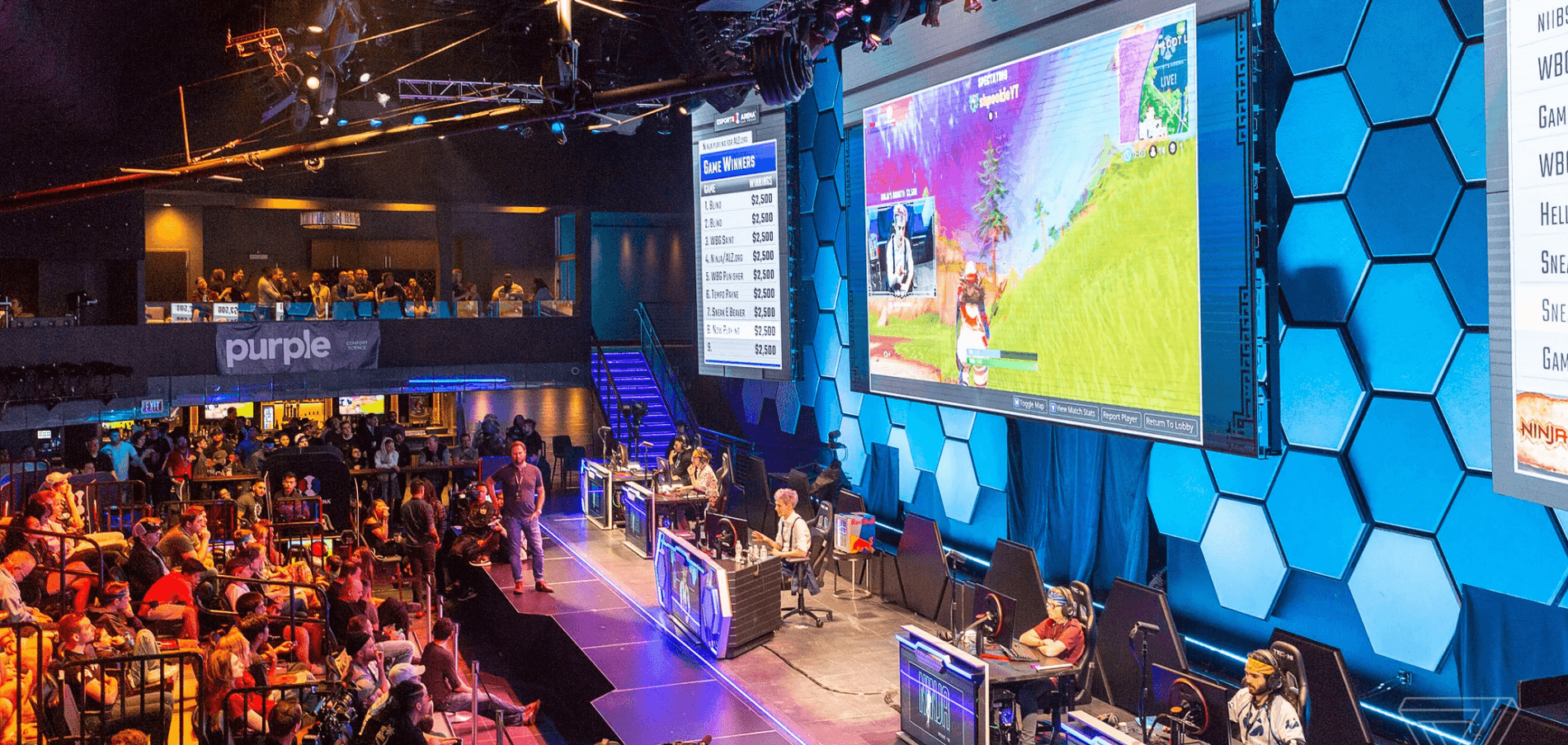

Celebrity streamers and fans at a gaming tournament in April 2018. Photo: Nick Statt, The Verge.

The growth of high-speed internet and competitive multiplayer gaming has also supported the rise of online HD streaming services like Twitch, Youtube Gaming, and various e-sports leagues. The level of audience interest and engagement with pro gamers and Twitch personalities is now high enough for thousands of people to play games for a living.

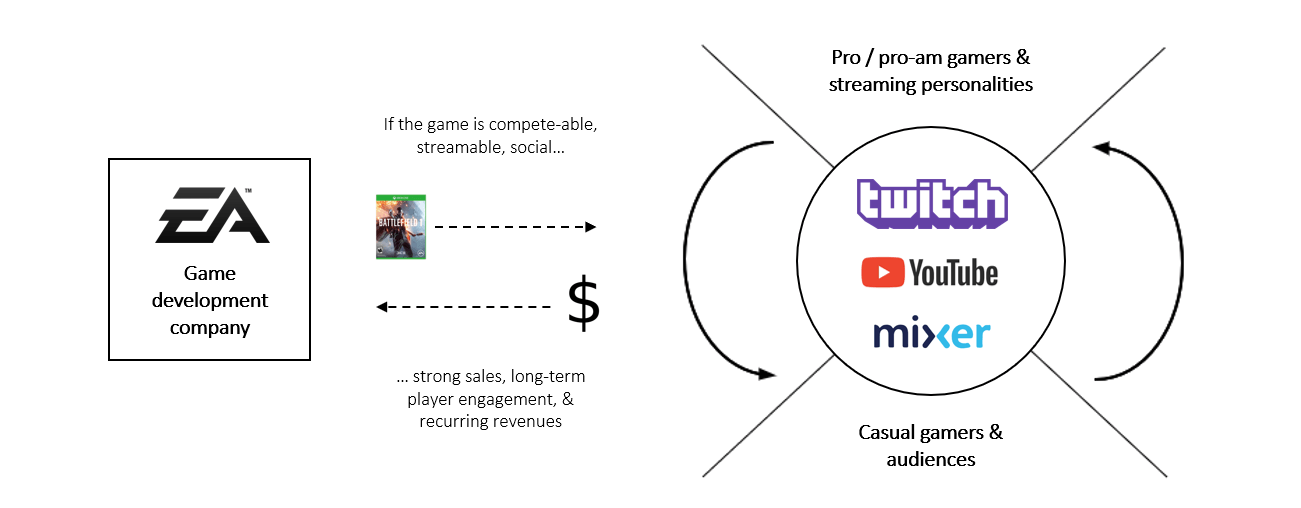

Together, these forces have served to create a growing network of pro and personality-driven streamers, their audiences, and the wider gaming public. Full-time gamers possess strong financial incentives to play only the most popular games to reach the highest subscriber bases and largest prize pools they can, intensifying the network effects of hit games; the releases best suited for competition and streaming draw the most interest from competitive gamers and streamers, introducing their established audiences to the game and effectively marketing it for free. As audience interest grows in a game, more people try playing it themselves, the potential for a pro community increases, and more streamers begin playing to ride the trend and capture a share of the game’s audience.

The implications for game companies are clear: find the right recipe to feed the streamer-viewer-gamer ecosystem, and you can end up with a runaway, blow-the-lights-out success like Minecraft, PUBG, or Fortnite. Get the recipe just slightly wrong, and the game — no matter how high-budget, well-reviewed, and effortfully marketed — could end up dead on arrival.

A revolution in gaming business models

High-speed internet has also enabled new digital distribution channels, allowing today’s gamers to download purchases directly from platforms like Steam and Xbox Live, and removing the need to buy a cartridge or disc from a store or e-retailer. For EA, the direct download platforms has created the potential for higher-margin sales, as Steam and other digital platforms are obviously asset-light and take a smaller cut of a game’s sale price than a store-based retailer like GameStop.

Additionally, as games have become more focused on social experiences and persistent communities, more and more players are now willing to make follow-on buys for access to expanded content and challenges (downloadable content, or DLC) as well as reiterative small-dollar purchases (microtransactions) for character skins, ornaments, and power-ups. Many of these in-game items cost little to nothing to develop, so the incremental sales they generate are usually extreme high-margin or pure profit.

Meanwhile, the arrival of revolutionary mobile hardware technology (powerful integrated chips, sensitive touch-screens, and high-res LCD and AMOLED displays) has turned every smartphone into a highly capable game platform — and thus nearly every user into a potential “gamer,” dramatically expanding the addressable market for gaming. Mobile also poses a threat to incumbents such as EA, however, as its traditional customer base of PC and console players are now presented with low-cost and increasingly attractive mobile gaming alternatives. Since mobile games can be developed with minimal resources, the Apple and Android App stores are now populated with tens of thousands of games, with hundreds more released each day, and frequently based on free-to-play (F2P) or freemium models. Furthermore, with free open-source game engines (such as Unity and Gamemaker) and unfettered access to digital distribution portals, it is easier than ever to develop and release indie console and PC games.

All considered, the shifting industry landscape has jeopardized several sources of EA’s historical competitive advantage. While EA could once control shelf space through its relationships with specialty and big-box retailers, games are increasingly downloaded from app stores and portals. Third-party developers can release titles direct to consumers, avoiding the need to partner with a publisher. Marketing advantages — including large advertising budgets and special market-power benefits (e.g., the ability to collude with industry journalists by trading preview access for sweetheart review scores) — are disappearing as consumers become more connected and responsive to independent commentators. The games market is more crowded, fragmented, and easier to enter than ever.

Ready player one

Based on all these trends, the prescription might seem simple: more mobile, more e-sports, leverage more data, grow a proprietary distribution platform, et cetera. If it were only so easy — in reality, EA understands these trends, and has already made reasonable reasonable efforts to capitalize on them. For instance, EA’s mobile division (EA Mobile) has been in operation since 2004, did over $600 million in revenue in 2017, and is still growing each year. The mobile initiative is already firing on all cylinders, so in my view, questions of how to best grow it are tactical rather than strategic in scope. Likewise, EA already has its own digital distribution platform (EA Origin), but due to the iron grip of the Microsoft and Playstation Stores on consoles, Origin is effectively limited to being a niche portal for EA’s PC titles. The company even established a competitive gaming division (EA CGD) in 2015, so an e-sports foundation is in place — but for now, it appears there is little pro or audience appetite for current EA titles to be played the competitive level. And as for data, EA already collects a lot of it from players, who are required to sign in to Origin during online sessions; although it is difficult to assess from the outside if EA is fully leveraging the data it collects, anecdotal evidence suggests EA and its peers are finding clever ways to use it to improve player experiences, marketing efforts, and to influence in-game purchases.

Right now, EA should focus on one thing above all: developing and publishing quality, compelling games that are built from bottom-up on the recurrent spending model. What’s the goal? Games that make money over long periods of time: successful releases that foster devoted communities, with high-margin tails fueled by follow-on microtransactions and incremental sales as players stay engaged and draw in their friends.

Naturally, EA’s executive team fully understands the value of this model; after all, this is a $40 billion dollar public enterprise run by highly competent managers. However, I would argue that EA’s recent string of failed releases and controversies — most notably, Star Wars Battlefront II, Mass Effect: Andromeda, Need for Speed Payback, UFC 3, and FIFA 18 — indicates that the company is struggling with systemic organizational deficiencies that are preventing steady execution on the model. Over time, EA has been moving fans of its longest-running series backward, rather than forward: new versions and sequels are more of the same, with no fresh features or innovations, but now with half of the content cordoned within secondary paywalls and hidden in buyable “loot boxes.” In my view, these are clumsy attempts to retrofit old-model game structures with new-model payment fixtures — and in doing so, there is no new value created. As such, EA’s efforts to capture more value necessarily leave its customers less well off, and widespread consumer dissatisfaction has been reflected in weak sales and popular criticism of EA’s business practices. If it wants to remain successful in coming years, EA should make several changes to address these problems.

Screenshot of a “loot crate” in EA’s Star Wars: Battlefront II. Under pressure from Disney and the gaming public, EA was forced to abandon its microtransaction model for the game, which had offered players the option to purchase credits redeemable for the crates in increments of up to $90.

First, EA must refresh its current approach to project planning and development. As we’ve discussed, the most popular contemporary games — releases that gain serious traction in the streamer-viewer-gamer network and attract prolonged engagement — typically succeed because they reward skilled players, encourage serious competition, and promote socialization. EA’s project managers and creative directors should focus more on these aspects as the critical “jobs to be done” while at the planning table. Today, EA releases are often (though not always) viewed easy to pick up, easy to master, and short on content; to keep players coming back, more resources should be directed toward the development of core game mechanics that are deep and nuanced. To improve quality and user experience, EA should opt for longer development cycles, even though that will raise production costs. More time for beta testing, data analysis, and the incorporation of player feedback will eventually pay off in better games with longer life cycles. Longer dev cycles can also help decrease EA’s notoriously high levels of employee burnout and brain drain, and give designers the time they need to do solid work. New incentive structures could encourage project managers to move away from short-term financial targets and instead optimize for long-term audience reach, engagement, and multi-year sales goals.

Second, strategies for microtransactions and DLC implementation should also be a major point of focus during core game planning. For a game with a full $60 sticker price, the trick is delivering enough content and value in the core package to make the consumer feel satisfied. A positive experience with the core product can then bridge gamers into limitless “end-game” experiences, where microtransaction offers are no longer viewed as predatory since the game’s implicit promise of value to the gamer is seen as fulfilled. (A shining example would be Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto V, one of the most successful games of all time, which led players into the open-ended micropayment bonanza GTA Online after the main game.) Another option is to limit microtransactions to cosmetic enhancements, encouraging players to differentiate their appearances without having to pay-to-win. Finally, EA can release a larger number of games as free-to-play or at discounted prices — as consumers are required to make less of an initial investment, better audience reach is possible, and tolls for additional content access receive are accepted with less contention. In fact, if more new games like this are released on EA’s growing $5-per-month subscription service, EA Access, it could help grow the value of the platform, attract more subscribers, and set the foundation for a new gaming ecoystem.

Third, EA should take a more active role in community maintenance and promoting engagement over time. Full-time community managers must be empowered and integrated on core development teams. Instead of shifting to new projects, lead game directors should be required to stay involved in their projects in the months and years after release, playing active and visible roles in their game communities. Developers should be engaged with the players and fans of their games, incorporating feedback into updates and new content add-ons. To achieve this, EA will have shift from a culture of “fire and forget” to one that encourages project teams to act as long-term community stewards. Refreshing the corporate culture, along with the company’s standard development processes and game models, will take time and concerted effort, but EA’s management team has signaled it is prepared to rise to the challenge.

Hi Chris – Thanks for the great read on EA’s opportunities and struggles as a game developer!

I think you’re correct that microtransactions and DLC should be a major point of focus for EA, but that they shouldn’t overlap with the core package. I remember the big fuss over the Star Wars Battlefront II loot crates. Most videogames used staggered in-game leveling to reward players who invest the time to level-up or unlock special items. To the gamer, this is a form of value creation — they use their hard work and time invested to enhance their in-game experience through unlocked items or boosted stats. When EA launched Battlefront II, it essentially monetized this leveling-up process, letting players with high WTP skip the hours of farming and questing to achieve max stats and all the special weapons. To the gaming community, those players had paid for their special status, but hadn’t earned it. Gamers also revolted over the randomness of loot crates in Battlefront II. While randomly generated/dropped weapons have long been features of RPGs and Action Adventure games (e.g., Fallout, Skyrim), players saw the randomness of loot crates as a blatant attempt by EA to force players to pay up for them.

I think you’re right about being intentional on what is your core product, and what are your add-on in-game purchases and DLC. Game developers have already found a good model for creating and capturing additional value from games: 3-6 months after a game’s release, the developer releases DLC for purchase in the form of new maps/quests/items. Many developers — including EA — have even packaged future DLC as discounted bundles, which can be purchased with the main game. But at the end of the day, you’re correct that the starting point is “developing and publishing quality, compelling games.” So long as EA continues to generate great new IP, it should do just fine.

Thanks Chris! How do you think about the changing views quality of release at release date? Before the internet, the logic was you had one release window, and there was no room for bugs in the final product. As internet speeds got faster, developers felt more confident in the ‘release early, patch often’ method. Then developers blurred the line between release further, allowing early access to Beta and Alpha stage of the game. Minecraft famously did this and essentially crowdsourced the debugging/development. Can large firms get in on this? It might have prevented things like the Mass Effect disaster.

That’s a great point! IMO, there is definitely an opportunity for large developers like EA to take advantage of early releases and longer closed & open betas. If decide to try more early access programs, it’s important that they price down appropriately and follow through on their initial promises to the players who buy in early. And long-form beta testing is a great way to build buzz, crowd-source bug-finding and feedback, and get to a better finished product EA does run open betas for its multiplayer games, but it’s usually done on a short timeline before the games get kicked out the door. In fact, the Battlefront II “loot box” wildfire broke out during the beta — EA DICE was doing the right thing by sourcing player feedback, but the problem was that the game producers initially refused to take corrective action in response.

As you point out, the Battlefront Lootbox fiasco, shows the importance of having something close to a finished product before releasing a beta. Especially with games like Halo, Star Wars, World of Warcraft or even FIFA that have very passionate and critical fan bases, I think it’s important you insure that whatever product you release (even if you tell players its a beta) is up to a standard that doesn’t erode that brand value the franchises have managed to build. New games like PUBG and Fortnite are able to do earlier releases but for big blockbusters games that are expected to be tentpoles for developers, I don’t know that you can apply the same methodology.

Thanks for the post, Chris! What an interesting industry to watch as new trends emerge and evolve so quickly. I absolutely agree that game companies should be focused on content development and seek to create hit games that people remain interested in over the long term. Reminds me of a case we has on King Digital Entertainment and Candy Crush.

I wonder what your thoughts are on AR/VR/mixed reality disrupting the current gaming market. The technology seems to be under developed at this point, but it also seems as though it is rapidly progressing, with many large tech companies around the world figuring out whether to be involved in the hardware or software or both. I do not know enough about this space to say what makes the most sense for EA, but I would guess that EA should remain in the software space and seek to have content on all platforms. It will be an interesting space to watch over the next 5 years!

Thanks for bringing this up, Mike, and I totally agree that the opportunities for both AR and VR are really interesting. I think games like “Pokémon Go” have shown us that there’s already a lot of potential for AR gaming today, and I’ve heard EA’s CEO say that they (particularly EA Mobile) are working on a lot of projects that will take advantage of it.

In time, I think VR has definitely the potential to change gaming, but it will probably take several more years (and at least one more console generation) for the tech to really take hold of the mass market. Since EA specializes in big budget, triple-A games, the install base just isn’t big enough yet to justify shifting a large amount of resources toward developing VR-first games. There shouldn’t be a rush to bet the farm on VR, either, as I don’t think see EA at risk of classic disruption here: full-featured VR games are expensive to develop, and when EA wants to start making more of them, they already have most of the tools and talent to do them well. As such, the safest and highest ROI bet is probably to start with ports of some key titles that could translate well to a VR experience (e.g. Anthem, Battlefield), focusing on developing institutional knowledge and optimizing the process. EA could also partner with startup studios and experiment with smaller in-house projects to learn more about building VR-first games from the ground-up, treating it as an investment in the future.

And as for the question of whether EA should enter the VR gaming hardware space, I think your instincts are totally correct on that — they should stick to software. It’s an early market that’s already crowded with a lot of players (HTC, Oculus, Playstation VR, more) who can do it better, and EA has no hardware expertise to begin with.

I saw this crazy shift in person a few weeks ago at the airport. I heard what sounded like a war movie and turned around to glare at the person who was rude enough to watch something on his phone in public without headphones (a major pet peeve) and was shocked when I saw a 12-year-old playing PUBG on his phone. I had heard that they were working on porting the game to mobile, but was amazed at how clear the picture was and how latency didn’t seem to be an issue at all. It truly is an amazing time for gaming.

Regarding microtransactions, I’ve read a lot about pushback from governments recently. Loot boxes in particular have been under scrutiny, with US regulators starting to look into them and The Netherlands declaring that they are considered gambling and thus must be removed from games. More regulation here may limit revenue in the short term for game makers, but I’d think the increased transparency will have long-term benefits.