Crowdfunding in Agriculture: Feeding the World

How crowdfunding in agriculture could unlock arable land, improve the wealth of small farmers in emerging markets and deliver strong returns to common people as investors.

Agriculture has been at the core of human history for thousands of years. It was what triggered the transition from nomadic to sedentary life and gave rise to the first cities and civilizations. Thousands of years afterwards, it is still playing a central role in modern world, where although the number of people depending on agriculture directly has been going down dramatically, production and crop yields are still a matter of huge debate.

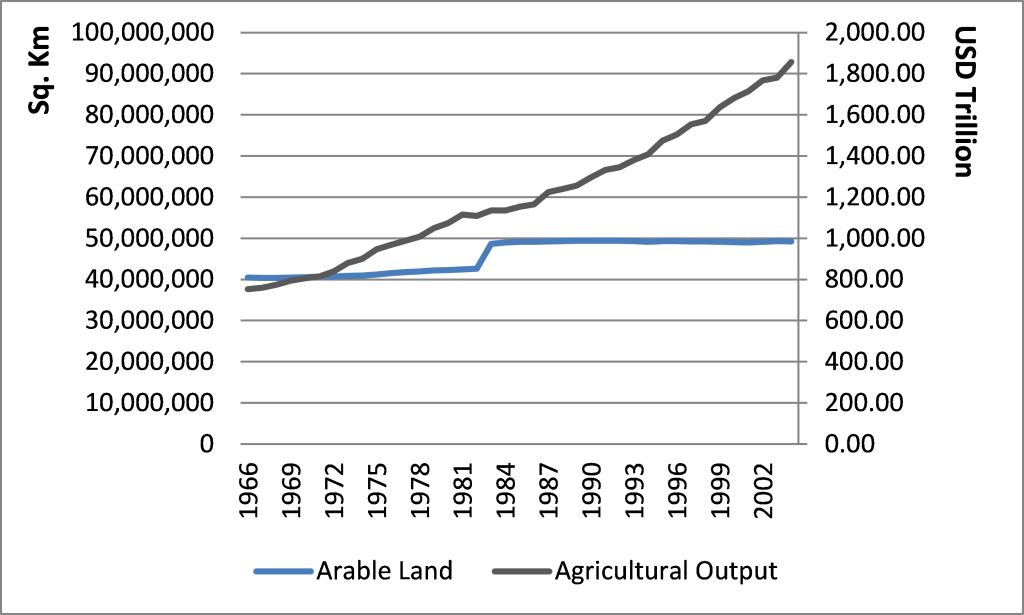

Nowadays, the vast majority of farmers in the developed world have adopted modern technologies to support their operations and the benefits have been clear. Farmers have been producing more food while minimizing their environmental impact. Additionally, in a business where land is becoming more scarce, the ability to increase yields plays a fundamental role in keeping the amount of arable land productive. This has supported the growth in agricultural output despite the fact that arable land has remained constant during the last 60 years.

Source: WorldBank

Still, in emerging economies the proportion of rural population is considerably higher, leading to a higher dependency on farming. In any given emerging country there are millions of small farmers whose land ownership does not exceed 10 hectares and cannot afford sophisticated equipment and capital expenditures. Given this, the return they get on the piece of land they own is low and their contribution to the overall output lags behind. To illustrate the above, let’s consider an alfalfa hay grower in Chile. The average cost of land of a “ready to produce field” is around US$40,000/hectare; costs of setting up the field are roughly $1,000 per hectare. Taking in count cost of machinery (only viable for lots of 20 hectares and above) the overall investment reaches $100,000. A rural farmer, whose income is less than $12,000 per year, is absolutely incapable of undertaking any of these investments. If they manage to find the equipment as many do (collaborative approaches, sharing, etc.), their yield reaches about 300 bales per hectare which at an average price of $6 per bale allows them to only pay back the costs of sowing during the first year. Given the 3-4 year cycle of the crop, the available cash after the whole term reaches around $10,000. The return on their real estate is 6.2% per year. In light of this reality, what ends up happening is that they usually seek employment in nearby industrial production centers, where they get the same money as a salary and avoid all the risk and pain of the entrepreneurial path. Additionally, land ends up idled.

On the opposite side, an “industrial farmer” who might undertake 300 to 1,000 hectares achieves yields around 700 to 800 bales per hectare. Following the math around $4,000-$5,000 per hectare of profit, which in 4 years and taking in count the sowing cost plus the amortization of equipment delivers returns around 10-12% on the real estate at a very low risk. It is worth mentioning that there is a wide range of crops that are exposed to this dynamics: Alfalfa and Soy are two of the most popular.

Now, where crowdfunding could play a role here? Given the economics, if a knowledgeable operator could put together a piece of land above 60 hectares, paying the land owner a fair market rent of $1,000 per hectare and base salary to take care of the minimum requirements of the field after sowing, the field could reach the 700-800 bale yields. This would generate an additional income for the farmer that would considerably improve his financial situation and deliver returns to the operator’s capital of above 30% per year (Rent + Variable Costs + Machinery of about $1,500 per year).

So what is preventing this from happening? There are two main reasons. The first one has to do with a cultural barrier, what is called the “farmers pride”. No small farmer will ever lease his land to the “big neighbor”. The second one has to do with the limitations those middle managers and people with technical knowledge have to overcome to become operators. But from a crowdfunding perspective, if one might put together a group of 20 to 30 small investors contributing from $3,000 to $5,000, the operator could overcome the cultural bias that “big neighbors” can’t and deliver returns to capital contributors above what any other investment opportunity would. At the same time, it would improve considerably the farmer’s economic situation and the efficient use of arable land. Clearly, a deal that works from an economic perspective and also generates huge social returns. This model has already been proved in the Argentinean soy industry and what started as small agribusiness investment funds has been growing to reach thousands of productive hectares and double digit returns to retail investors.

Note: Source of financial figures and market prices for hay and cost of production haven been researched from ODEPA (Research and Agrarian Policies), an agency of the Chilean Government (http://www.odepa.cl/estadisticas/productivas/)

Very interesting approach Charles! Sounds like a great solution to increase efficiency in small farms and give small farmers the chance to earn higher income, while keeping the economic activity of these locations, with local suppliers for bigger farming or industrial processes, keeping overall costs lower. Do you know who developed and organized this model in Argentina? Was it the government or private parties? In the Argentinian experience, are all these small farms next to each other? How far away can they be in order for the model to work?

Usually they need to be within a 20-30 km radio. This allows the operator to achieve the economies of scale necessary without increasing transportation costs or moving the machinery. In the Argentinian model, they started as close end investment funds and they ended up as investment tools provided by asset managers to wealthy people, with minimum tickets above a million dollars. The flexibility of this has to do with the modularity. You can do it with 2,000 hectares, like the Argentinean case, or with 60. The laters requires low capital and can be sourced by small contributions.

Thanks Charles, very interesting post. I like your idea of an operator using lease contracts to piece together larger plots of land and to improve yields through investment. However, I wonder whether crowdfunding is the best source of capital. The types of investments you’re speaking of require very patient investors who are willing to stomach illiquidity. Moreover, they would benefit from investors providing technical know-how (about agriculture, local real estate regulations, etc.) in addition to capital. As such, why wouldn’t the appropriate organizational structure for the operator look more like an agriculture-based private equity firm? For instance, Black River Asset Management, the private equity affiliate of agriculture giant Cargill, could be the right investor given its ultra-long-term capital and significant agriculture domain knowledge (i.e. they already know what investments should be made).

Alternatively, a vendor of agriculture seeds/equipment/services could operate a leasing program of the type you’re proposing with meaningful synergies versus an independent crowdfunded operator. For example, Monsanto, a publicly traded seeds/agrochemical company, would not only capture the ~30% ROI you suggest any operator could, but would also benefit from an expanded addressable market for its core products.

Even if we suppose that private equity firms and agriculture vendors can’t or won’t pursue your idea for whatever reason, why is crowdfunding superior to standard partnerships? If, as you suggest, the operator only needs 20-30 investors, he/she wouldn’t need a digital platform to find investors and it wouldn’t be worth the investment to create one. Alternatively, you could argue that someone could set up a digital platform to pair potential operators with investors. However, this presumes there’s a critical mass of operators interested in this business model but who can’t access funds in more traditional ways – it’s not clear that there’s a large enough network to merit an independent digital platform.

I think what you say is definitely true. To address your second point, the investor profile depends on the crop you want to target. In the case of alfalfa or soy for example, it is in fact easy to return the cash. Look at it like a bond. You saw, then harvest every year returning interest + principal. The only residual value comes from the disposal of the assets (tractors and machinery). So you are getting the value through the whole period. For other types of things, like vineyards or walnuts, then it is definitely true that the crowd would not work given 15 or even 20 year cycles.

Regarding why using a crowd, I see it as the easiest tool operators can use to build a business. What you mention about agriculture vendors makes a lot of sense. Actually I studied this model working for a seed producer. By doing this, they would integrate vertically and provide even more value to their clients, securing part of the demand for their own products.

Thanks for the post, Charles. Very Interesting!

If I’m understanding this correctly, the value unlocked here is by helping farmers overcome their “pride”. They have land, which it doesn’t make sense for them to own (because ideally they should diversify) or cultivate (because of economies of scale, e.g., with machinery). Unfortunately, they’re unwilling to lease it to a faceless corporation. So really all we need is to give them a short list of investors, and possibly throw in a friendly meeting between the farmer and the investors, to make the farmer comfortable with the deal.

My concern would be that the farmers would very soon realize that they are, in fact, “selling out”. Still, this is definitely an innovative use of crowdsourcing.

The pride is a hurdle that prevents big industrials (or neighbor companies) from doing it. The point here is that the farmers won’t understand nor will want to relate to a bunch of people. That is why you need a friendly operator who speaks the farmers’ “language” and intermediates the crowd.

Regarding your second point, the unlock of value given the higher return of the land is so high, that farmer get very well compensated. Remember that by his own, he cannot do it given (1) size of the plot (2) restriction in the access to capital. And unfortunately these are barriers that will remain and prevent him from ever doing it on his own.