Can Strava grow beyond just “outdoor sport enthusiasts?”

Since it’s founding in 2009, Strava has attempted to brand itself as the “social network for athletes.” While the app has grown to be one of the go-to apps for serious runner, cyclists, and other outdoor athletes, can Strava make inroads with the mass consumer market?

Since it’s founding in 2009, Strava has attempted to brand itself as the “social network for athletes.” However, even though the app has grown to be one of the go-to apps for serious runner, cyclists, and other outdoor athletes, the app has failed to make inroads with the mass consumer market.

Fitness trackers and their associated communities have blown up over the past 10 to 15 years, with platforms such as RunKeeper, MyFitnessPal, MapMyRun, and Nike+ among top competition for Strava. What is unique about Strava is that it is one of the few that has managed to remain privately owned, whereas many of its competitors have been swept under major athletic brands such as Under Armour, Asics, and Nike.

Strava offers much of what the other apps in this space offer – the ability to track a workout, measure and store data, share workouts with friends, and compete in online challenges. With over 1 billion activities uploaded onto the platform to date, Strava has proven successful primarily within the outdoor athlete market, but it hasn’t been enough to capture the attention of more mainstream athletes. Strava has been able to capture so much of its niche market by offering the app for free to all athletes, with of course the option to upgrade to a premium subscription for $7.99/month. The other revenue stream that Strava relies on is Strava Metro – a service whereby Strava sells the data it captures to urban planners and governments’ transportation departments to enable them to study and improve traffic and commuting patterns. With clear benefits for both of these revenue streams to expanding the user base and increasing engagement on the platform, it comes as no surprise then that Strava has recently tried to do just that.

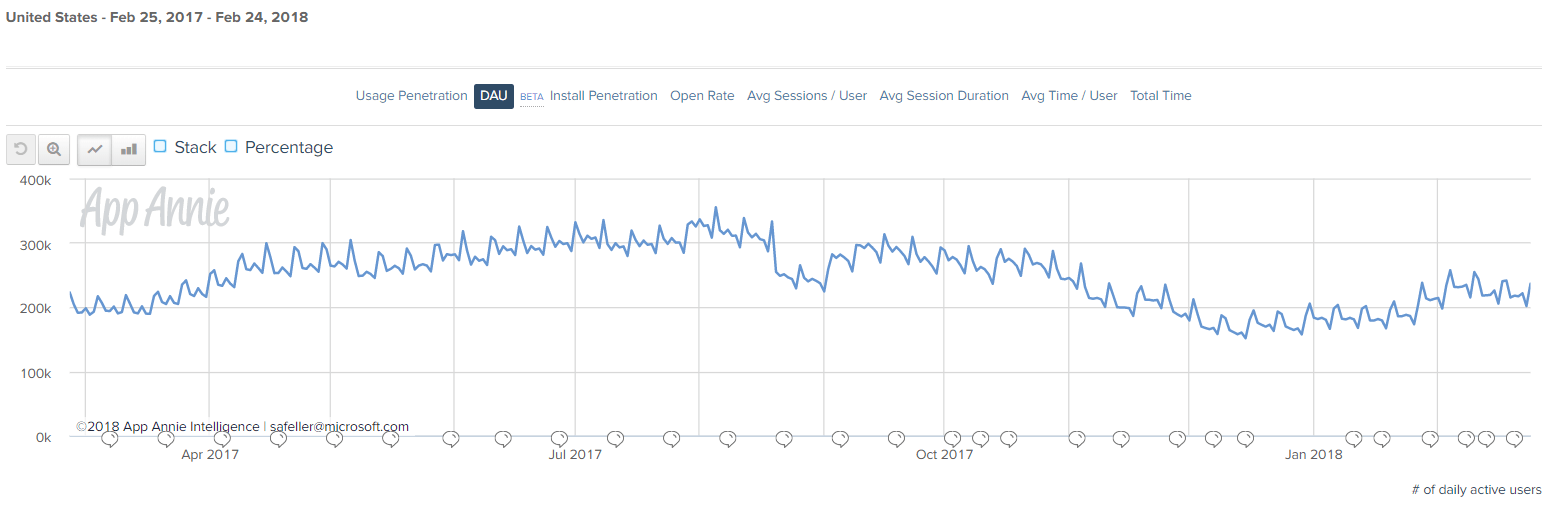

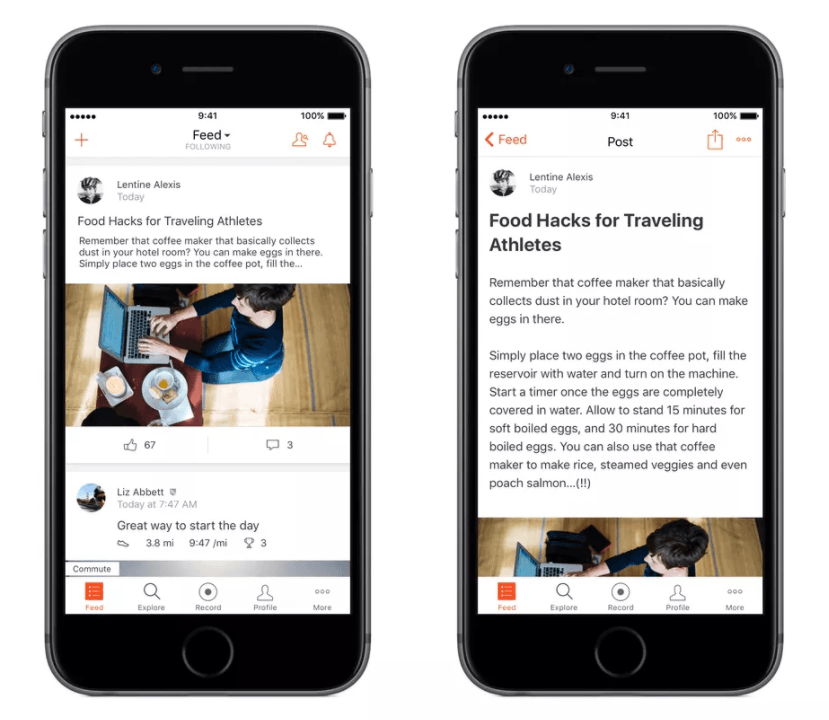

Critics of Strava claim that the app hasn’t done enough to enable users to engage with one another freely and more deeply on the platform. Even though previously users could post notes and stories in addition to sharing their workout data, Strava meaningfully changed this this past October with the introduction of a new feature called posts. Posts now enable users to share non-activity stories, post articles and photos, and engage in conversations with other users. According to AppAnnie (see exhibit below) daily active users (DAU) haven’t improved at all, and in fact have declined slightly since last October, suggesting that this hasn’t increased current user engagement.

But that isn’t all – Strava has announced near-term plans to become a “discovery experience” for things such as running clubs or best coffee spots. All signs point to Strava being more friendly to users who want to engage more socially on the platform, but the burning question that remains is whether or not users will choose to spend more of their social networking.

While I believe that Strava’s attempt to integrate more social network features into its platform may help its current niche users to engage even more with the platform, I worry that this isn’t enough to bring today’s non-users onto the platform – a critical win in order to be the go-to “social network for athletes.” There remain two major barriers for today’s non-users: high switching costs and high same-side network effects. First, most fitness-tracking apps lock users in relatively early by building up and storing a user’s data over time. For example, for a runner who has run with Nike+ for 3 years and has all of their run history contained in that app, there is no solution for transferring this data backlog out of Nike+. For this reason, the barriers are extremely high for an existing user to switch over to a new platform since they lose this history. Second, there exist same-side network effects for users. As a runner on the Nike+ platform, the value to me increases as more of my network also chooses to engage with this platform since it enables us to communicate, share, and compete all on the same platform.

Given these barriers to adoption for these non-users, Strava may be better off sticking to their niche-yet-engaged following and trying to expand within that.

Sources:

https://www.theverge.com/2017/5/2/15511118/strava-fitness-tracking-app-athlete-posts-social-network

https://www.digitaltrends.com/outdoors/strava-posts-social-network/

https://www.appannie.com/apps/ios/app/strava-running-cycling-gps/details/

http://www.businessinsider.com/interview-strava-ceo-james-quarles-social-network-2017-12

My concern for Strava is that if they focus on engaging just their existing user base, their attrition will eventually outpace their growth to begin their decline. If they can’t bring on new users, their data won’t be as compelling of an offering to governments and urban planners. Many of the companies in this space have expanded into wearables to ensure seamless tracking. It makes sense that Strava would not have the capacity to develop into this area, but pushing into a recommendations service does not seem that inspired, especially with the number of big players in that space.

Thanks for posting this. I recently switched over from RunKeeper to Strava due to serious peer pressure from a group of friends. While I understand how the social networking could be an avenue to drive user engagement, I would argue that it can actually negatively affect the user experience as well. I ended up making my profile private because each of my runs had started to feel like a ‘performance’ where I had to beat my PR to get kudos from my friends. I’ve also noticed that when people run less-than-stellar times they feel compelled to write notes like ‘easy run’ or ‘recovering from an injury’ and I wonder whether this social pressure actually does more harm than good. Finally, a ‘Strava Best’ recently started following me (unsolicited) and invited me to join a group called ‘ONLY SEX.’ When I reached out to customer service about blocking this they admitted that they had a number of such users and were working to identify them and remove them from the platform. All this to say, being more social comes with a new set of problems that may actually be counter productive when trying to scale into the mass market.