Will COP21 put traditional utilities out of business?

If the signatories of the COP21 Paris agreement are to meet the commitments therein, carbon pricing is bound to play an increasingly important role in global markets. This post analyses how a higher future carbon price might affect utility companies and how that impact varies depending on their investment in clean sources of energy.

On December 12, 2015 the leaders of 195 nations reached a historic agreement at the COP21 in Paris to keep the increase in global temperature well below 2oC above pre-industrial levels and to aim to limit the increase to 1.5oC. The agreement was opened for signature on April 22nd, 2016 in New York and, as of today, has 192 signatories. Of which, 97 have deposited their instruments of ratification – meaning that it will enter into force…TODAY1.

But that raises the question of implementation: What should (or can) governments do to influence the behaviour of companies and individuals such that the objectives set in Paris will be honoured? One increasingly popular answer is setting a price on carbon.

The principle is simple: putting a price on carbon emissions captures (some) of the value that was previously lost in the form of a so-called “externality cost” and makes those responsible for it, pay for it. And it does so in the most economically efficient way, by allowing those market participants that can reduce emissions at a lower cost do the bulk of the work, while pricing out inefficient polluters.

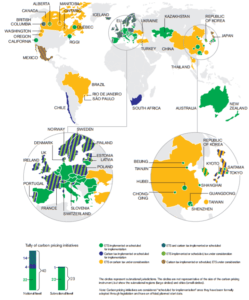

Today some 40 countries and over 20 cities, states and provinces have bought into this idea and implemented carbon pricing schemes in some form or another (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Summary map of existing, emerging and potential regional, national and subnational carbon pricing initiatives (Emissions Trading System and tax) 3

But how are those countries that have introduced carbon pricing schemes doing in terms of emissions reductions?

Launched in 2005, the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), is the first and biggest carbon pricing program in the world4. According to the European Commission’s website the EU is “well on track towards meeting its emissions reduction targets for 2020, set under the 2020 climate & energy package and the Kyoto Protocol”5 largely thanks to the EU ETS. However, the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) argues that under its current structure, the EU ETS will not be able to deliver the volume of emissions reductions necessary to meet the targets set in Paris. And that is because the price of carbon is thought to be (and expected to continue to be) too low. IETA estimates that to achieve this level of emissions cuts, a tonne of CO2 will need to cost around €406. The closing price on November 3rd, 2016 was €6.47.

What if the EU recognised this incentive gap and decided to lower its emissions cap to push the price of CO2 up to that level? How strong a signal would that send to polluters?

To assess this question, one might look at how a price of €40 CO2t would impact the P&L of companies within a certain industry. In the EU, energy production remains the highest contributing sector to greenhouse gas emissions7, so if the overriding objective of setting a price on carbon is to reduce those emissions, analysing the impact on utilities seemed to me like the obvious choice.

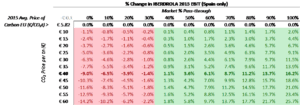

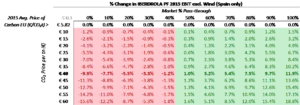

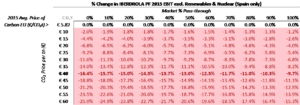

What I thought would make this analysis even more interesting, is looking at how that impact varies depending on the extent to which a particular company has decided to hedge itself against this foreseeable price increase by investing in clean generation technologies. In that spirit, the next section focuses on analysing the hypothetical impact of an increase in the price of CO2 emissions on IBERDROLA: a Spanish utility with over €31.4bn in sales in 2015, 46.5 GW of installed capacity (of which 56% is derived from renewable sources and 7% from nuclear energy), and 31,000 employees that serve 34 million customers mainly in Spain, the UK, the US, Mexico and Brazil8.

The results are the following9:

In other words, in a Paris-compliant scenario where CO2 would be priced at €40 per tonne, IBERDROLA would be much worse off had it not invested heavily in clean10 sources of energy. That is because by virtue of having a cleaner generation base than the market average, the cost of CO2 per MWh would be lower for IBERDROLA than for the average market participant. How much worse (or better) off depends on how much of the additional cost is passed through to consumers. If the market % pass-through is low (for example, due to regulatory reasons), IBERDROLA would have to absorb the additional cost, which would have a negative impact on its earnings – albeit less negative than if it didn’t have renewables. If, on the other hand, market % pass-through is high, having invested in renewables will yield higher earnings for IBERDROLA, given that the market price will increase by more than the additional cost per MWh incurred by the Company.

In short: should carbon prices increase to a level that is consistent with the commitments made in Paris, traditional utilities that have not invested in clean sources of energy are likely to be priced out of the market. And by then, it may well be too late.

Word count: (800)

1 Thirty days after the date on which at least 55 Parties to the Convention accounting in total for at least an estimated 55 % of the total global greenhouse gas emissions have deposited their instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession with the Depositary.

2 The World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon#CarbonPricing, accessed on (3rd November 2016).

3 World Bank Group and ECOFYS, Carbon Pricing Watch 2016 (2016), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/24288/CarbonPricingWatch2016.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

4 European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/index_en.htm, accessed on (3rd November 2016).

5 European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/progress/index_en.htm, accessed on (3rd November 2016).

6 IETA, GHG Market Sentiment Survey 2016 (2016), http://www.ieta.org/resources/Resources/GHG_Market_Sentiment_Survey/IETA%20GHG%20Sentiment%20Survey%202016.pdf.

7 European Environment Agency, http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/data-viewers/greenhouse-gases-viewer, (accessed on 3rd November 2016).

8 IBERDROLA 2015 Annual Report; IBERDROLA 2015 Sustainability Report.

9 To isolate the effect of an increase in the price of carbon on IBERDROLA’s financials (in this case EBIT), the analysis focuses exclusively on the Spanish market. This market has three defining characteristics that make it especially well-suited for this exercise:

- It operates under the EU ETS

- Pricing is determined by a marginal pricing system, i.e. demand is satisfied with the lowest cost energy mix possible

- It is barely interconnected (total volume of electricity exported and imported as a percentage of total production in 2015 was just 11%, compared to 20% in Germany, 15% in France, 20% in Italy, 29% in Portugal and 40% in Belgium). Meaning that demand and supply are not heavily influenced by external forces

The analysis also makes the following assumptions:

- Demand is assumed to be completely inelastic. That is, the increase in the price of electricity due to the increase in the price of CO2 does not cause any reduction in demand

- The 2015 average daily and intraday day electricity price is used as the base price for the analysis

- IBEDROLA’s pro-forma EBIT excluding Renewables and Nuclear is calculated assuming that these technologies have share the same EBIT margin per MWh as other generation technologies included under IBERDROLA’s “Generation and Clients” reporting segment

10 Although I have included nuclear energy as “clean” source of energy for the purpose of this analysis given its CO2 neutrality, I believe that this energy resource seldom fits that description.

I just wonder if the EU puts itself at a disadvantage by doing these sorts of schemes – you see this too in the car industry. Europe has stifled a lot of industry and jobs, at the same time as not really doing much to help innovation. Is Iberdrola forced to do this in its operations outside of Europe?

I would argue that while there may be a cost disadvantage in the short-term, in the long-run companies that have operated under the EU ETS will be better off. There is a clear global trend towards implementing carbon pricing schemes and those companies that have started investing in increased energy efficiency – in the case of utilities, in clean sources of energy – early, will have a stronger a competitive position when the cost of carbon increases.

If by this you mean investing in renewables, I don’t think Iberdrola is forced to do so inside or outside of Europe. I would say that they have chosen to invest (both in European markets and outside), among other reasons, to diversify their generation base in anticipation of a hike in the price of carbon.

Very interesting read and a nice topic that captures more of a broader view of climate change as opposed to a company specific one. Putting a price on pollution is a sure way to align companies bottom line incentives with incentives of governments to hamstring climate change. I do wonder though about countries like China and Russia who are still industrializing and still have large incentives to continue polluting. Granted China is the largest producer in the world and they did not pollute the world as much as the USA and Western Europe did over the course of the 1900s. They would argue that it’s unfair to ask them to slow down their production to be more environmentally conscious, while we were not environmentally conscious when we developed our countries. So if China and Russia don’t follow these rules and are some of the worlds largest producers do we have to cut our emissions even more to make up for them?

That is definitely true and probably the reason why climate agreements in the past have been somewhat unsuccessful. But this is precisely what makes the Paris agreement such a breakthrough. It is effectively the first time that the two biggest emitters in the world have been able to agree on a common target. While China may have in the past made the argument that they should not be “paying” for the pollution that the west caused, I think they have also realized that climate change is likely to have more damaging effects on them than on the US in terms of climate-led mass migration. And that has led them to agree to the Paris emissions reduction target.

It is also true that in many emerging countries that have a higher percentage of their population living in rural areas that are not connected to the grid, renewable technologies present a much more viable option for electrification. For instance, to get electricity to a small town in the middle of China it is much easier (and cheaper) to build a few solar panels or a windmill next to the town than to embark on a huge infrastructure project to expand the grid so that it will reach them. I think this is also playing a part.

Jose, fascinating question and I enjoyed your methodical and thorough analysis. IBERDROLA is an interesting case study (and while you exclusively focused on Spanish assets, they have also been active in M&A in the northeastern US, as you may know). I think its ironic that in a heavily regulated industry, the actions of the government may result in the bankruptcy of many utilities, but I suppose that is a minor cost to bear if we are to stave off the worst effects of climate change. How do you think CEOs and executives at large utilities such as IBERDROLA should view transitioning to renewables and nuclear? Should companies commission new greenfield projects in order to develop the expertise of operating these assets, or should they view wind, solar, etc assets as acquisition targets to diversify their asset base in preparation for the carbon pricing scheme?

Jose, I particularly like the topic you’ve chosen. In the past few years that I’ve been active in the energy space (including as a manager of the renewable generation and efficiency portfolio of a Swiss utility), I have observed a so called “war” against traditional utilities. While I do acknowledge that historically they have been artificially benefiting from very high returns at almost no risk (and still do in many countries under the pass-through tariff regimes that you’ve mentioned), I also believe they have the potential to be front-runners in the transition towards renewable generation, especially given their holistic understanding of the power system. However, I think the biggest problem they are facing (that makes it quite difficult to venture out of their traditional assets) is the regulation uncertainty, especially in Spain, where the government has had such an abrupt downwards shift in support schemes during the past 4 years. I share your hope that COP 21 will result in higher levels of support (be they in the cap and trade or more recent tendering schemes), but what I believe will truly change the game and allow utilities to use their immense know how into becoming front runners of the transition, is the long term commitment of the participant states (indeed a more meaningful crowd than Kyoto’s). Tomorrow’s elections will probably give us a good first signal of this potential.

Sometimes I wonder if carbon markets are actually slowing down the transition to disaggregated grid systems. Carbon schemes are constructed with large projects and established utilities in mind, and while pushing utilities towards renewable energy certainly isn’t a bad thing, a world that doesn’t have such a reliance on central grid systems may be a more efficient use of our attention. In the U.S. alone, we lose 6% of generated energy in transmission and distribution (or 69 trillion Btu), and an additional 22 quadrillion Btu are lost in generation (http://insideenergy.org/2015/11/06/lost-in-transmission-how-much-electricity-disappears-between-a-power-plant-and-your-plug/). Distributed grid systems, with an emphasis on solar, could be the wave of the future and save substantial amounts of energy loses in our ever-aging transmission system around the world (e.g., transmission losses in India approach 30% of generated power). If utilities invest substantially in renewables, will this give them an excuse to not update their transmission systems and attempt to stop the development of micro-grids? I wonder…