United Launch Alliance: Rocket Without an Engine

The effect of isolationism on the space industry.

During my time working at Space Exploration Technologies, I witnessed the downfall of the United Launch Alliance (ULA), the predominant player in the government launch industry. At the time, SpaceX was gaining momentum in breaking ULA’s monopoly on lucrative national security launches that they had held for the past decade. This became far more pronounced when in 2014, U.S. sanctions threatened to cut off ULA’s supply chain of Russian manufactured rocket engines. Over the course of these events, I watched to see how they would attempt to solve the problem of owning a rocket without an engine.

United Launch Alliance Origins

The United Launch Alliance was formed in 2006 as a 50-50 joint venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin [1]. Before the joint venture, both companies had competed in the United States Air Force’s (USAF) Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program. The EELV program began in 1994 as a solution to create launch systems to serve National Security Space (NSS) launch requirements [2] and ensure the United States government would always have access to space.

The joint venture gave ULA control over Lockheed Martin’s workhorse rocket, the Atlas V. ULA then went on an unprecedented run with a 100% success rate over 100 launches from 2006 to 2015 [3]. Their position as sole provider of government launches finally came to an end, however, when SpaceX became EELV certified in 2015. Future EELV launches would then be opened up for competition between ULA and SpaceX for the first time since 2006.

Atlas V and the RD-180

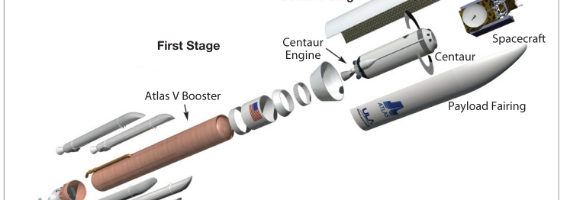

Before becoming ULA’s go-to rocket, the Atlas V was developed by Lockheed Martin using the core design of ICBMs from the Cold War [5]. In an interesting twist, they teamed up with Russian rocket scientists leftover from the collapse of the Soviet Union in order to prevent dangerous technology getting into the hands of other emerging powers [4]. These Russian scientists were far ahead of their American counterparts in rocket engine technology so Lockheed Martin incorporated the RD-180 into its Atlas V vehicle. NPO Energomash, the Russian based manufacturer, ended up supplying engines at a fixed price of $1 billion USD for 101 RD-180s [10]. Somehow the United States’ national security found itself critically relying on a Russian import.

Russia’s Annexation of Crimea

This precarious situation came to a head in the beginning of 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea amid worldwide disapproval, with the United States and European Union laying sanctions on Russian officials. Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin who was also the head of the Russian space program, replied in a tweet:

“I suggest to the USA to bring their astronauts to the International Space Station using a trampoline.”

Senator John McCain led the charge to end reliance on the RD-180 with his introduction of legislation to effectively ban it as an import [7]. The RD-180 ban passed the Senate floor, allocating only 18 RD-180s with a hard cutoff on December 31, 2022 [8].

ULA Response

ULA’s board decided to replace their current CEO Michael Gass, who had held the position since ULA’s founding, with the more dynamic Tory Bruno [9]. Tory Bruno rallied ULA’s powerful lobbying force led by Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama, whose state contained thousands of ULA employees. In addition, ULA refused to bid for their first EELV contract since SpaceX became certified, citing a lack of available RD-180s among other reasons. These moves enhanced U.S. space concerns and the Senate passed an amendment to allow the RD-180 imports once again on June 15, 2017 [12] in order to ensure access to space.

Meanwhile, their next generation launch vehicle, the Vulcan, was announced. The Vulcan set its earliest launch date to 2019 and estimated a “bare bones” price of $82 million [11]. ULA would partner with Blue Origin, an aerospace company run by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, to manufacture new engines domestically.

Personal Recommendations

ULA’s current plan for Vulcan needs to be far more ambitious. With SpaceX now successfully reusing rocket boosters, ULA will only be able to compete if they can reduce launch prices far below their projected $82 million goal. By the time Vulcan is introduced, it may already be overly expensive and using outdated technology. On a positive note, Blue Origin shows promise as a domestic supplier of rocket engines and will once and for all end ULA’s reliance on Russia.

One fundamental question remains. ULA’s Atlas V launch vehicle has demonstrated incredible consistency, something not to be overlooked when payloads cost in the $100 million range. With the RD-180 ban officially over, is it worth the investment and time to create an entirely new launch vehicle with the Vulcan program?

(773 words)

[1] Bloomberg News, “Lockheed and Boeing to Form Rocket Launching Venture,” The New York Times, May 3, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/03/business/lockheed-and-boeing-to-form-rocket-launching-venture.html?_r=0, accessed November 2017.

[2] Air Force Space Command, “Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicles,” published March 22, 2017, http://www.afspc.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Article/249026/evolved-expendable-launch-vehicle/, accessed November 2017.

[3] Mike Wall, “Dazzling Rocket Launch Marks 100th Liftoff for United Launch Alliance,” Space.com, published October 2, 2015, https://www.space.com/30738-united-launch-alliance-100th-rocket-launch.html, accessed November 2017.

[4] Andy Pasztor, “Post-Soviet Pacts Spawned U.S. Reliance on Russian Rocket Engines,” The Wallstreet Journal, September 4, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/post-soviet-pacts-spawned-u-s-reliance-on-russian-rocket-engines-1504526401, accessed November 2017.

[5] William J. Broad, “The World; A Missile That Would Make Lenin Faint,” The New York Times, September 22, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/22/weekinreview/the-world-a-missile-that-would-make-lenin-faint.html, accessed November 2017.

[6] NBC News, “Trampoline to Space? Russian Official Tells NASA to Take a Flying Leap,” published April 29, 2014, https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/ukraine-crisis/trampoline-space-russian-official-tells-nasa-take-flying-leap-n92616, accessed November 2017.

[7] John McCain, “McCain & McCarthy Bill Targets Russian Rocket Engines,” published January 27, 2016, https://www.mccain.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=d25046ac-4381-440f-a609-7b0fbcc5d7e2, accessed November 2017.

[8] Marcia Smith, ”Senate Reaches Agreement on Russian RD-180 Engines,” SpacePolicyOnline.com, published June 14, 2016, https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/senate-agreement-reaches-on-russian-rd-180-engines/, accessed November 2017.

[9] James Tutten, “ULA Board Members Replace Founding CEO and President Michael Gass,” SpaceFlightInsider.com, published August 13, 2014, http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/organizations/ula/ula-replaces-founding-ceo-president-michael-gass/, accessed November 2017.

[10] Chris Gebhardt, “U.S. Debates Atlas V RD-180 Ban, ULA’s Non-Bid for Military Launch, NASASpaceFlight.com, published January 29, 2016, https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2016/01/u-s-debates-atlas-v-rd-180-ban-ulas-non-bid-military/, accessed November 2017.

[11] Chris Gebhardt and Chris Bergin, “World Launch Markets Look Towards Rocket Reusability,” NASASpaceFlight.com, published June 24, 2015, https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/06/world-launch-markets-rocket-reusability/, accessed November 2017.

[12] Jeff Foust, “Amendment to Senate Bill Allows Continued Imports of Russian Rocket Engines,” Space News, published June 15, 2017, http://spacenews.com/amendment-to-senate-bill-allows-continued-imports-of-russian-rocket-engines/, accessed November 2017.

Curtis, this is a fascinating post! I really liked it. I had no idea that the rocket launch industry has been under so much pressure from trade isolationism in the last few years. I really liked your insight into the relationships between the space industry and global political events, as well as your insights into the business side of the launch industry. It is really interesting that ULA is investing in a vehicle that is likely to be uncompetitive vs. SpaceX. Even from an outside perspective (having listened to various Musk speeches about the cost advantages of a reusable rocket), it does strike me as strange. There must be a rationale for investing in Vulcan – whether it is because they believe SpaceX does not have the capacity to do the number of launches that will be required, whether it is the first step in investing in a series of increasingly more economical (albeit not reusable) rockets, or whether there are other advantages to the rocket (e.g., able to handle bigger payload, etc.)

To answer your question about whether it is worth developing a new launch vehicle, with the ban being over – I think it is worth developing a new launch vehicle capable of using engines that come from suppliers which are less ‘risky’ to source from. The current situation means that ULA is sourcing from a single supplier that has high political risks. To de-risk the long-term sustainability of ULA, it is important to de-risk the supply engines.

Fascinating read, Curtis. I generally agree with Dan’s logic above: developing a new launch vehicle breaks your reliance on a single supplier if you’re the ULA. Though, I also believe in the utility (both technical and diplomatic) of a healthy trade relationship between the Russians the Americans when it comes the RD-180s. If I had a vote, I’d probably lean towards encouraging the reopening of trade per Congress’s recent effort.

I read ULA’s potentially unstable supply of RD-180s as an opportunity for ULA, Blue Origin, and the larger project of space exploration for one key reason: it could encourage faster development of key technologies that allow the industry to advance overall. When so much of the R+D in this sector is concentrated in a few firms and government-sponsored agencies, progress is slow as there isn’t the existential imperative that keeps firms innovating in well-functioning, competitive markets (man’s “last frontier” is being explored with Cold War technology…). This lack of dynamism seems to result in a conservative mentality where “good enough” is accepted — especially when it comes to costs. I guess my hope would be that while Vulcan might ultimately be an expensive bust, it does provide the community of engineers and managers working in this sector a valuable learning opportunity. The more projects for new launch vehicles or booster designs that are greenlighted, the more failures (of both projects and firms) we’re likely to see. However, ideally, this failure is the very thing that speeds along progress for the sector as a whole.

While I agree that the ULA will need to lower costs to keep up with SpaceX, I wonder what is more valuable: healthy competition between two worthy rivals or coordination between all parties? Is there a possibility that SpaceX could collaborate with the ULA to reach an even better outcome than any one party can reach on their own? According to Fortune, ULA has said that it is cost-cutting to keep up, noting that it would eliminate approximately 25% of its workforce [1]. Is this healthy for ULA? Will this cause better outcomes in the future? While I understand the concern that a lone incumbent can become complacent, I challenge that the stakes are high in this industry and that the government should want to ensure the best possible outcome from a quality perspective, not just a price perspective.

[1] David Z. Morris, “Is SpaceX Undercutting the Competition Even More Than Anyone Thought?,” Fortune, June 17, 2017, http://fortune.com/2017/06/17/spacex-launch-cost-competition/, accessed November 2017.

Very nice article!

It is so interesting to see how space exploration has shifted from military and politics to something our entire economy now relies on. It is also fascinating that private companies are now more and more involved in the space industry and triggering a revolution.

Since the topic is so interesting, you could have elaborated further on ULA’s strategy and on your suggestions. What does being more ambitious translate to? Should they partner with other private partners? What is the government strategy?

I would also have loved to learn more about the US domestic competition and how SpaceX, BlueOrigin and other players see themselves sharing the space launch market.

In order to answer your question, I would think that the US not only needs its own space engine solution but it also needs to regain its leadership. It is much more than an financial decision but also a very political one and a matter of national security [1].

[1]: Linda L. Haller and Melvin S. Sakazaki, “Commercial Space and United States National Security”, https://fas.org/spp/eprint/article06.html, Accessed November 2017

Super interesting!

A few questions. First – why were Russian scientists more advanced than US scientists after the Cold War? I always thought the narrative was that the biggest challenge in space engineering was to put a man on the moon, and since the US accomplished that and the USSR did not, I took that as presumptive proof that the US had better rocket science. Is this untrue, or had the US advantage eroded in the intervening 20 years? If so, why/how did it erode? It feels like a real shame.

I also wonder about Boeing’s recent announcement [1] that they are working with the Air Force on the development of a new ICBM. Given the similarities between ICBM engines and space-launch engines, I wonder, is this a potential third competitor as a US-made low-earth orbit engine?

Finally, given the technology overlap between ICBM capabilities and space capabilities (both are launching payloads into space?), I would love to hear your opinion as to the impact of the US’s lagging in space technology on the nation’s defensive readiness? Is the US’s nuclear deterrent diminished due to a reliance on Russian space technology?

[1] http://boeing.mediaroom.com/2017-08-21-Boeing-Awarded-Design-Work-for-New-Intercontinental-Ballistic-Missile

Wow! Thanks Curtis for bringing this event and topic to our attention! I see this as two cautionary tales:

First, as we learned in the FuYao Glass case, a producer’s choice of the right supplier is vitally important. In the case you describe here, ULA has not only tied their fate to a competing rocket technology firm but also one in a country with whom the US has a precarious relationship. Hindsight being 20/20, I would have recommended ULA move this technical expertise in house to avoid full dependence on its supplier for this mission critical component. I believe this is a competitive advantage that SpaceX has been able to leverage as it ramped up production of its rockets.

Second, this is one case where I see Section 232 of the Trade Protection Act being extremely useful in preventing issues faced by ULA. Section 232 allows the President of the United States to unilaterally levy tariffs or other trade regulations to protect industries necessary to national defense [1]. Space exploration and supply of our nation’s space stations, I would argue, is vital to our national defense. Had protectionist measures taken place proactively, ULA would never found itself in this position in the first place.

[1] Thomas Biesheuvel and Jonathan Stearns, “How Trump’s ‘Hammer’ on Chinese Steel Could Hit the U.S.,” Bloomberg Politics, August 2, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-11/where-trump-s-war-on-foreign-steel-might-lead-quicktake-q-a, accessed November 2017.

Curtis, this is SO interesting!

Rocket technology has to be one of the most expensive, slowest to develop, highest risk, and guarded technologies out there, and of course I can’t imagine there are many companies out there developing new engines! Given how state-run the space industry was and how mistrusting the United States is becoming of Russia, would you know if there are other aspects threatened by global isolationism? Given the high cost of products and few number of players, how has isolationism impacted pricing for these parts in the space industry? Would love to learn more.

Great post! I echo Matt’s thoughts on this industry. With revenues from space launch for the public very far from a technological and regulatory perspective, this is a tough industry to be in. The founding of Blue Origin was very interesting to me. The significant monetary backing of Bezos, Bezos’s eye for diversification within this industry, and the ability to monetize any technologies that arise from Blue Origin’s development will be key to their success in my opinion. I think ULA will only benefit from more competition. I also share Adam’s and others curiosity about the role of government in bringing forth this cutting edge technology. According to the article below, it seems that many state and federal politicians are taking notice and are considering tax credits and other incentives. I believe that this government support will be key both from a regulatory and monetary perspective in this space. Do we know of any other significant initiatives by the government to move this technology along?

[1] Alan Boyle “Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space venture has plans for big expansion of Seattle-area HQ” Geekwire February 22, 2017 https://www.geekwire.com/2017/jeff-bezos-blue-origin-hq/

Amazing article Curtis! I had no clue that Russia’s annexation of Crimea had this impact on space exploration. In an industry such as this, I wonder how proactive could ULA have been in sourcing engines from different suppliers, it seems like this industry has very few players, and I wonder if the fact that they had exclusivity was what made them inert to seek to innovate. It seems that the decision to ban the RD-180, would have given Space X free rein to bump their prices if the ban hadn’t been lifted, causing the government to pay more because of this decision.

Your article is very illuminating not only as a supply chain issue but also as a leadership lesson. As a business leader, we must be prepared for the unexpected, and I think that a company should avoid getting too comfortable and have contingency plans in place for when a competitor enters the market or an unforeseen political issue arises.

Great article!

It’s interesting that governments are focused on implementing policies to regulate their space industries, but aren’t focused too heavily on how to plug the gaps created by their policies.

This seems to be leaving private companies to capitalise on the opportunities that these policies are creating, which will eventually accelerate the privatisation of the space industry. But will this actually be counter-productive to the world’s governments’ agendas? Given the space industry’s strategic importance from a security perspective, will losing control of this industry lead to a loosening of security in the long term?

I guess time will tell!