Unilever: The Problem of Water

Water is the elixir of life. How can one of the world’s largest companies help save the world?

We experience climate change primarily through water[1]. It affects both our supply and demand of water. On the supply side, we suffer from the unpredictable quantity and declining quality of freshwater. Receding glaciers or longer dry periods affect seasonal water flows and reduce the amount of water flowing through rivers, cutting off drinking water and water for industrial use. Rising surface temperatures can cause toxic bacteria in water to proliferate, reducing the quality of the water. On the demand side, farmers may demand more water for irrigation due to rising temperatures.[2]

By 2025, two-thirds of the world’s population will not be able to access as much water as they need[3]. The Water Resources Group projects that the global demand for freshwater will exceed supply by 40% in 2030[4], if business and consumers carry on with today’s consumption practices.

The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan

Unilever is one of the world’s largest Consumer Packaged Goods companies, with businesses in Personal Care, Household, Foods and Refreshments (beverages and ice cream). With worldwide reach in all countries but six, and a supply chain touching 7,600 suppliers[5], its businesses have a huge global footprint.

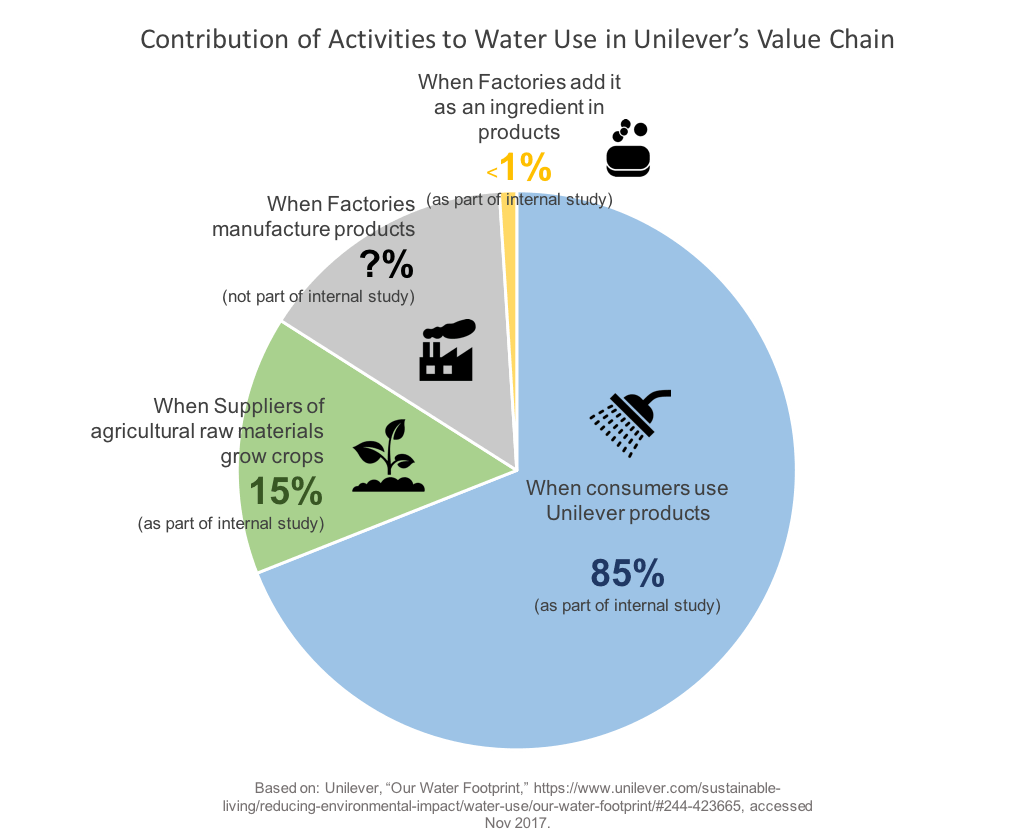

In 2010, Unilever’s chief executive, Paul Polman, declared that Unilever would double the size of the business while halving its environmental footprint by 2020[6]. One of the key metrics Unilever tracks as part of the Unilever Sustainable Living Program is water use, which they aim to halve by 2020[7]. While the business has not yet doubled (EUR 52.7bn TO in 2016[8], against EUR 40bn in 2009[9]), the company has made some progress in reducing water use. Unilever directly or indirectly uses water at four different points in their value chain.

As of 2016, their water impact through consumer use has decreased by 7% since 2010[10]. The launch of Comfort One-Rinse laundry detergent in India in 2012[11] remains one of the strongest product-based initiatives in developing markets. In developing markets, 40% of household water used is used in washing clothes[12]. With Comfort One-Rinse, consumers only need one bucket of water instead of three to rinse out the detergent[13]. As Unilever launches the product in new regions at a measured pace, more needs to be done to accelerate the reduction of consumers’ water consumption in the short-to-medium term.

Unilever has been working with suppliers to reduce water consumption through promoting drip irrigation. This method involves supplying water to crops through tubes in small quantities, reducing surface runoff and water waste, and promises to reduce water use by 50%[14]. Conversion will take time given the costs and process changes involved, and we will likely only see improvements in the medium-to-long term.

Unilever seems to have made the most palpable reduction in water extraction in their manufacturing operations, likely due to the level of control they have over their own processes. They have used 18.7mn fewer cubic meters of water compared to 2008 levels, representing a 37% reduction[15]. They expect 2020 levels of use to be below 2008 levels, despite an increase in production volume[16]. Although we are unclear of the impact of this on water use in their entire value chain, this is still a commendable improvement and reinforces their commitment to saving water despite not hitting consumer targets.

Recommendations

The biggest gaps Unilever is facing are reducing the bulk of water used by consumers and suppliers. Unilever can further drive this agenda through:

- Developing more product innovations to reduce water usage

- Speeding up changes to suppliers’ processes to reduce water consumption

More studies should be conducted to identify other areas in which consumers use a disproportionate amount of water, e.g. while bathing or cooking. A low-hanging fruit for Unilever is to extend the use of One-Rinse technology to shower products, in the hope that consumers will take shorter showers and hence, use less water. All water-saving products should be accompanied by clear usage instructions so consumers know they don’t have to spend as much time rinsing themselves as before.

Agriculture is still the world’s largest withdrawer of freshwater and contributor to wastewater, consuming 38% and contributing 32% in the form of waste[17]. While we wait for drip irrigation to slowly pervade supplier practices, perhaps there is a way for Unilever to encourage suppliers to collect excess runoff water and channel it back into the current irrigation system. Unilever could speed up the process by setting targets for suppliers to meet in terms of water savings, and incentivize them by recognizing them as “preferred suppliers” or through monetary awards.

Eliciting behavior and system changes in consumers and suppliers takes years, and perhaps this is why Unilever is still far from its target. Is education enough to get consumers to change their water consumption? How can we get suppliers to convert their practices quickly?

Word Count: 796

[1] UN Water, “Climate Change Adaptation: The Pivotal Role of Water,” http://www.unwater.org/publications/climate-change-adaptation-pivotal-role-water/, p. 5, accessed Nov 2017.

[2] Ibid.

[3] UN Water, “Water and Climate Change,” http://www.unwater.org/water-facts/climate-change, accessed Nov 2017.

[4] The Water Resources Group, “Briefing report prepared for the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting” (2012), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF/WRG_Background_Impact_and_Way_Forward.pdf, p. 17, accessed Nov 2017.

[5] Vivienne Walt, “Unilever CEO Paul Polman’s Plan to Save the World,” Fortune.com, February 17, 2017, http://fortune.com/2017/02/17/unilever-paul-polman-responsibility-growth/, accessed Nov 2017.

[6] Unilever, “About our Strategy,” https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/our-strategy/about-our-strategy/, accessed Nov 2017.

[7] Unilever, 2016 Annual Report, p. 13, https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-annual-report-and-accounts-2016_tcm244-498880_en.pdf, accessed Nov 2017.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Unilever, 2010 Annual Report, p. 23, https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-ar10_tcm244-421849_en.pdf, accessed Nov 2017.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Unilever, “Helping consumers save water,” https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/reducing-environmental-impact/water-use/helping-consumers-save-water/#244-423666, accessed Nov 2017.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Unilever, “Working with suppliers & farmers to manage water use,” https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/reducing-environmental-impact/water-use/working-with-our-suppliers-and-farmers-to-manage-water-use/#244-423668, accessed Nov 2017.

[15] Unilever, “Reduce water abstracted by manufacturing sites,” https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/reducing-environmental-impact/water-use/#244-503774, accessed Nov 2017.

[16] Ibid.

[17] UNESCO, “Wastewater, The Untapped Resource” (2017), http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002471/247153e.pdf, p. 9, accessed Nov 2017.

Thanks, Larissa. Enjoyed reading this! I think Unilever and Paul Polman have been great beacons for driving sustainable supply chain practices and corporate focus on sustainability. Polman’s shift to reporting every 6 months instead of every quarter remains one of the more awesome ways I’ve seen a company begin to focus on longer-term performance. In short, love it!

How likely do you feel it is that Unilever will hit its goal of doubling the business and halving the environmental footprint by 2020? With only two years remaining, I don’t think its going to happen. Much of this comes down to the difficulty you note in changing behaviors of ~7,600 suppliers across the globe. With that in mind and the clock ticking, it feels like both of your options 1 & 2 won’t get the company there. I wonder if it’d be better for Unilever to double down in specific sectors or product categories (like detergents, as you note) to show that the goals are possible in some areas of the business? Would there be specific sectors where there is a concentrated number of suppliers that Unilever has some serious influence over? I could envisage a scenario in which Unilever can have disproportionate impact in some areas and thus have something remarkable to show for its efforts by 2020 rather than good but effectively failing results across the board.

Thank you Isabelle for this very insightful article on one of the most pressing (and often most insufficiently covered) global issues. The fact that, according to the Water Resources Group, the global demand for freshwater will exceed supply by 40% already in 2030 (!), should be a major alarm signal for humanity and all multinationals to engage and reduce the end-to-end water consumption of their supply chains.

While Unilever has clearly initiated strong efforts this respect, as outlined by you, I think a case study analysis of Nestle, one of the other leading companies worldwide with respect to water footprint, can also be very helpful for Unilever’s continuous optimization. For example, Nestle engages actively in reducing water usage at their suppliers’ farms in developing countries by i) teaching improved water usage practices and ii) connecting farmers with advanced seeds manufacturers (e.g. Syngenta) reducing the required water usage of growing plants. In addition, Nestle also has built “Zero water factories (e.g. in Brazil) allowing the company to extract and use water from milk through a process of evaporation”[1] which is then subsequently re-used in factories for cleaning and cooling processes. As outlined by you, water reduction is a slow process as it requires many different adjustments across an entire supply chain. However, the urgency on this topic leaves no other option than to engage immediately and decisively.

________________

[1] Nestle, Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2016 (Feb 2017)

Thanks for sharing – I agree with you and other commenters that Unilever’s commitment to this cause is commendable. As I think about reducing water usage, there are two sets of people that Unilever can influence: suppliers and end customers. On the supplier side, I support your recommendation that Unilever choose “preferred” suppliers – Unilever definitely has the scale / buying power to convince suppliers to reduce water consumption. They should also work with suppliers to figure out which actions are most effective and share these best practices across the supplier base.

I think the consumer side is more difficult because Unilever has to fundamentally change customer behavior, which is deeply ingrained (i.e., decade-long habits). The product innovations you mentioned (detergent or shampoo formulations) could alter behavior in emerging markets. However, I think they would be less effective in developed markets, where access to water is not an issue. I’d be curious to see what types of actions will create meaningful impacts in developed markets.

Finally, I wonder if Unilever can market its sustainability mission more effectively. I was unaware that Unilever was focused on this before reading your article, and now I want to buy more Unilever products! I think a lot of consumers care about supporting sustainable products and it would be a really effective way to differentiate Unilever’s brand.

It’s interesting to learn about Unilever’s efforts in this area of adapting ecologically sustainable practices. As your article and the comments point out, the target Unilever is striving for might be unrealistically aspirational given where they are seven years into the decade. However, their progress so far is indeed praise-worthy.

I would like to highlight two aspects on this issue with respect to the two sides of the value chain:

1. Customers:

The most tangible way for CPG companies is probably through their advertising. I wonder if Unilever will start emphasizing the environment-friendliness of its products in their promotions on print and digital media. This presents a critical trade-off that a company needs to decide on – whether to focus on the real value-add the product offers the consumer versus the social benefit of being an environmentally savvy global citizen. Every second of the consumer’s time-share and mind-share that Unilever spends spreading the awareness around water-conservation is a second less in highlighting why the product is great.

2. Suppliers:

Unilever’s sustainability efforts on the supplier side have been limited only to the agricultural raw materials and the company has conveniently ignored talking about industrial raw materials altogether. This concerns me about whether this entire initiative is actually genuine.

The industrial raw materials that Unilever uses in its products, such as soda ash for laundry detergents, chemicals used in soaps, crude oil derivatives used as material bases in several of their products, etc., use enormous amounts of water in their production / refining processes. Given the commoditized nature of some of these raw materials, it is easy for the suppliers to focus solely on cost reduction rather than using environmentally sustainable processes. It will be interesting to see if Unilever takes some measures to enforce water-conservatism in this part of the supply chain as well.

I really enjoyed reading your analysis of looking at the water problem from the customer and supplier sides of a large multinational company, Unilever. I believe that large corporations play an increasingly crucial role in resolving some of the world’s pressing challenges. That is the trick of being part of the supply chain system – all players need to be on board. To answer your last questions:

1) Education is necessary to get consumers change their water consumption, but I don’t think it is enough. Behavior change is one of the most difficult things to do and it takes extremely large amounts of time, costs and commitments. That’s why I think engaging large companies is a key because it not only has sufficient resources to keep investing in the mission but also has technologies to creatively alter consumer patterns. As you mentioned, Unilever should commit to more product innovations to reduce water usage without making consumers start the practice on their own.

2) I think big companies also have power to get suppliers convert their practices quickly. There are more they can do than selecting “preferred suppliers” or offering monetary awards as you suggested. For example, big companies can help finance suppliers to convert their practices or put in joint efforts to work on the conversion together.

Thank you for writing this! It’s really interesting to read about such a massive company adopting really aggressive and optimistic targets in light of climate change, although I share Pranay’s concerns about whether Unilever will enforce these goals up the supply chain.

One thing that seems like a broad concern as companies adapt to climate change is that their incentives are sometimes misaligned with consumers. For instance, you suggest extending the use of One-Rinse technology to shower products. While this certainly makes sense from an ecological perspective, consumers might be resistant to adopting these technologies if they prefer taking long showers. In contrast, it makes sense that drip agriculture might be more aligned with farmers’ incentives, as it lowers costs.

In addition to Pranay’s concerns about early suppliers in the supply chain, I’d be curious to explore how Unilever is viewing the risks of pushing more eco-friendly products on a consumer base that hasn’t fully acknowledged the scope of climate change.