The National Flood Insurance Program: Do the Math

The US National Flood Insurance Program is not yet adaptable to climate change, leaving millions of Americans at risk.

The US National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) began as a government-subsidized effort to provide insurance against floods causing immense damages. Against rising sea levels and increased flooding from climate change, the NFIP’s future remains bleak, imperiling millions of homeowners across newly and more severely flood-prone communities.

A High-Risk Program

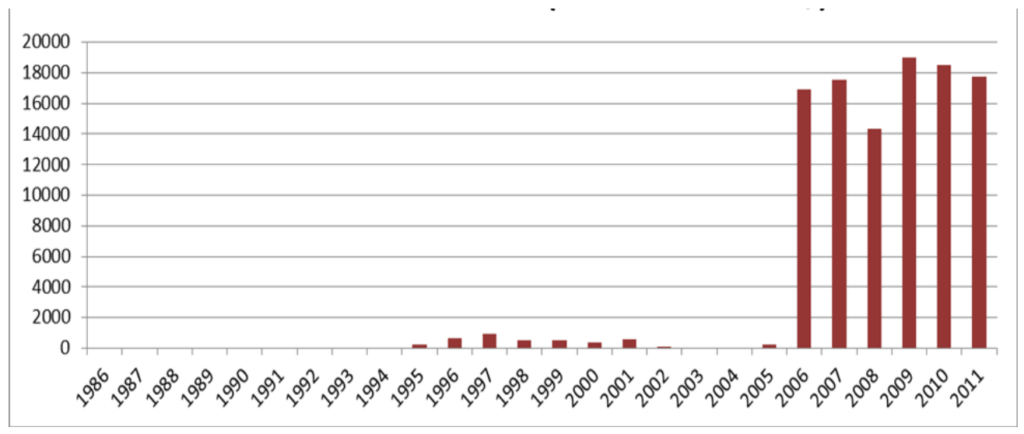

Since 2006, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the US Federal Government’s auditor, has listed the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) on the “High-Risk List”.[1] The list indicates to Congress a collection of programs GAO finds most at risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or in need of transformation.[2] Administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), NFIP offers flood insurance to property owners and enforces flood-reducing guidance.[3] While the GAO reports a number of factors for their judgment, the agency cites climate change as a critical structural threat to the program’s financial solvency. FEMA today owes $23 billion, up from $20 billion in November 2012, composed of flood insurance claims including those from hurricanes in 2005 and 2012.[4]

As climate change’s impacts continue, the GAO finds that those “responsible for [the NFIP] had done little to develop [information] to understand their long-term exposure to climate change… and had not analyzed…impacts of an increase in the frequency or severity of weather-related events on their operations.”[5]

The National Flood Insurance Program

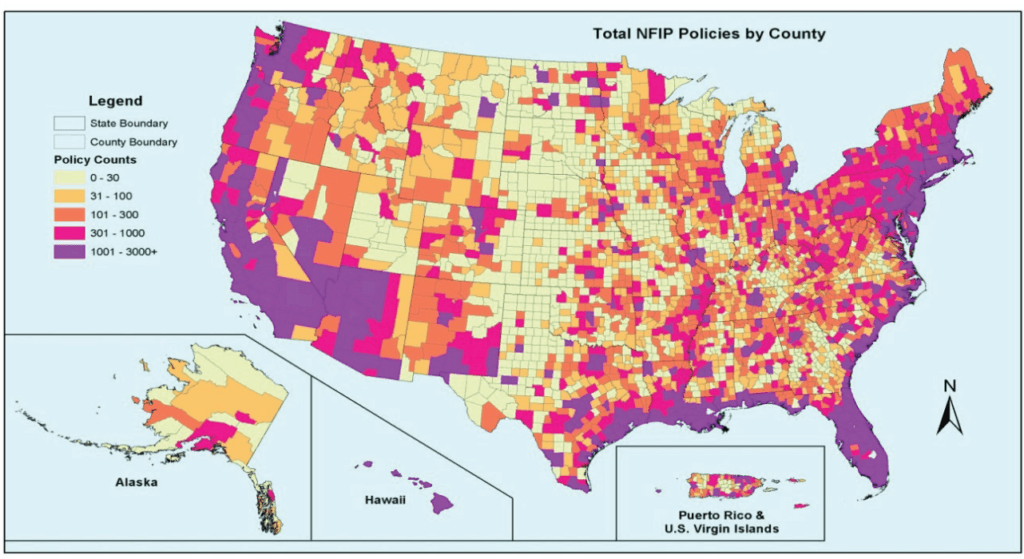

The NFIP today insures 5.5 million policies, 60% located in Florida, Texas, and Louisiana.[6] Takeup rates remain low, particularly outside Special Flood Hazard Areas–areas most prone to flood damage.[7] At least 9 million live in these SFHAs, sharply reducing the premium pool necessary for payouts.[8]

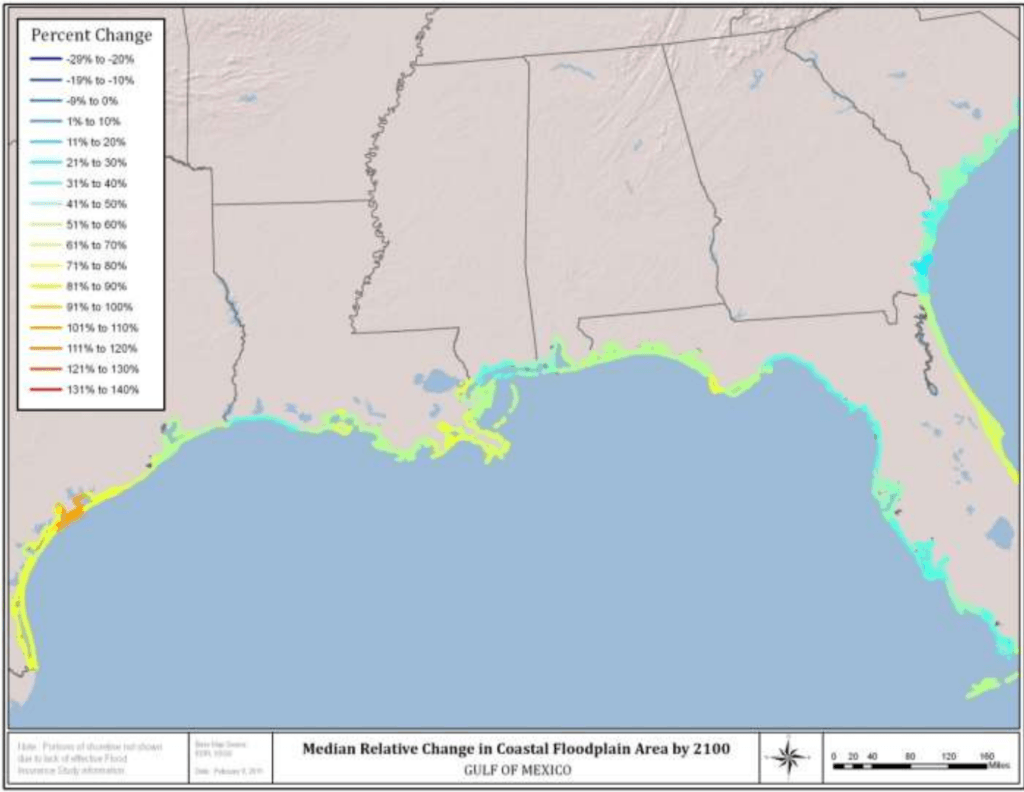

FEMA, faced with existing debt from past hurricanes, remains underfunded and unable to address a future with increases in flooding frequency. A 2015 Nature Climate Change letter finds “strong evidence [for] an [increase in] frequency of flooding” in the central United States.[9] A 2013 NOAA report found that many communities have and will continue to see increases in flooding. The NFIP in current state will remain questionably, if not conclusively, insolvent as funding commitments fall behind expected growth in flood frequency.

Actions to Date

The agency is re-evaluating its flood risk estimates from the 1970s and 1980s era estimates. A 2013 Association of State Floodplain Managers report estimated it would cost “as much as $7.5 billion to bring FEMA’s maps up-to-date.”[10] The data private insurers and FEMA itself uses for estimating flood damages remains out-of-date and unable to accurately provide estimates for today’s true risk premiums.

Congress in 2012 attempted to raise the flood premium rates, only to reduce some rates in 2014 under pressure. The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act left homeowners, including many in the areas affected by Hurricane Sandy, with significantly higher premiums. With the public pressure, the Congress reduced rates, with no other solutions for the larger question of an unsustainable NFIP.[11]

What can FEMA do?

FEMA is in a difficult position as a program with significant liabilities and highly exposed to political pressure. Fundamentally, the NFIP must either reduce its liabilities or increase its premiums through price or volume. Political leaders and federal agencies may be able to invest in preventive flood measures to reduce the overall cost post-natural disaster. This directs public funds not just to recovering, but efforts to update communities and infrastructure to rising sea levels and increased flooding from climate change.

Federal, state, and local governments may further use incentives and penalties to influence home ownership away from the riskiest floodplains. There is no tenable scenario where public institutions ignore affected communities. To stem the cost and length of recovery, incentivizing and discouraging settlements in SFHAs and other high-risk flood plains remains an additional option to sustain NFIP.

FEMA has no completely palatable options to deal with rising sea levels and flood frequency. The political, fiscal, and public policy complications enforce a status quo unfit to deal with climate change hazards.

Words: 645

- National Flood Insurance Program, High-Risk List (February 2015), p. 385 http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/668415.pdf, accessed November 2016.

- Government Accountability Office, “High-Risk List,” http://www.gao.gov/highrisk/overview, accessed November 2016.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency, “About the NFIP”, https://www.floodsmart.gov/floodsmart/pages/about/nfip_overview.jsp, accessed November 2016.

- High-Risk List, p. 77

- Ibid.

- Locations of Potential Affordability Challenges, Affordability of National Flood Insurance Program Premiums (2015), p. 77, National Academy of Sciences.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency, “What is a Special Flood Hazard Area?”, https://www.floodsmart.gov/floodsmart/pages/faqs/what-is-a-special-flood-hazard-area.jsp, accessed November 2016.

- PBS, “How Federal Flood Maps Ignore the Risks of Climate Change”, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/how-federal-flood-maps-ignore-the-risks-of-climate-change/, accessed November 2016.

- The changing nature of flooding across the central United States, Nature Climate Change (September 2014), http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v5/n3/full/nclimate2516.html, accessed November 2016.

- PBS, “How Federal Flood Maps Ignore the Risks of Climate Change”, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/how-federal-flood-maps-ignore-the-risks-of-climate-change/, accessed November 2016.

- Ibid.

It sounds like the inherent risk flood insurance protects against has increased and the program has not adapted to meet this changing risk (instead relying on 1970s and 1980s estimates). You say there are “no palatable options” to deal with this – which seems a little pessimistic. It seems like there’s actually quite a lot the program could do to become more viable – first, they could refuse to insure homes built in flood plains (the demand for water front property has led to homes being built in these areas) – ideally this would reduce the demand/sale-ability of these homes so developers would stop developing in flood plains. Second, they could raise premiums for those with the highest flood risk, to better cover the cost of the risk being protected against (and again, further dissuade buyers from purchasing homes in high risk areas). As you note, the first step is to update estimates so that these decisions can be made based on current data. Great post – thanks for sharing!

Very interesting post on flood insurance. I was not aware of the severity of these implications and am surprised the NFIP seems to be complacent in their preventative actions. It would be interesting to take a deeper look at what preventative flood measures are being used inside the home as you mentioned in your closing section. With the advent of the Internet of Things, I would assume that there are some innovative connected home devices that could be leveraged in flood detection and prevention. Insurance providers could subsidize the cost of installing these for homeowners (similar to how they subsidize and install fire alarms) which would put one more control in place to catch home flooding in its early stages.