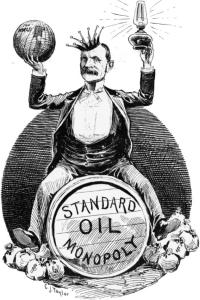

Standard Oil – A Company So Effective, Only the U.S. Government Could Compete with it

In 1870, John D. Rockefeller created Standard Oil, a company that would go on to create the foundations of the modern oil & gas industry, force new business laws to be created, and become the first monopoly in the U.S.

Creating and Dominating an Industry

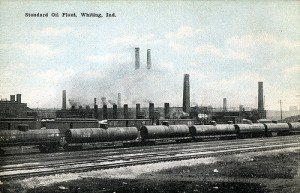

What started as a pure-play refinery in 1870, Standard Oil (“SO”) became a fully integrated, industrial behemoth with a 90% market share in kerosene refining, and perhaps one of the most effective corporations ever created. In fact, SO was such an effective company, that the U.S. government had to create a new law – the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 – specifically to combat the market power that SO (the first trust ever created) had built for itself.

The Value Proposition and Business Model

Kerosene was the refined version of crude oil that powered the U.S., and many of the developed global economies, for most of the latter half of the 19th century. In the 1860s the process for refining was inefficient and resulted in products of inconsistent quality. As a result, the refining process was expensive, wasteful, and produced low yields. Procurement of inputs was also expensive; crude oil was transported by rail in individually filled wooden barrels that were time consuming to fil, often leaked, and were expensive to produce. Furthermore, given the low yield of refiners, railroads often had to stop at many small refiners to get a full load and thus had to charge higher costs to maintain profitability.

The inefficiencies in this market provided SO an opportunity to create a product of uniform quality that could be sold to consumers at the lowest possible price.

Solving the Problem

SO made several key changes to the kerosene production process from improving the refining process itself, to reorganizing the whole value creation chain from raw materials procurement to customer delivery:

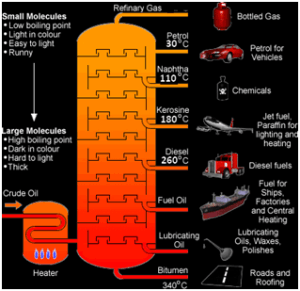

- Improving the refining process: Kerosene was extracted from crude oil through fractional distillation and then purified by the addition of sulfuric acid, an expensive chemical compound. SO developed a kerosene that could be produced with 1/5 the sulfuric acid used by competitors, thus greatly reducing costs of production.

- Waste reduction: Historically, the 40% of crude that was not kerosene was often discarded by kerosene refiners. SO extracted and sold the other byproducts (e.g. paraffin wax and gasoline) to other refiners of those products. Furthermore, some of the gasoline was used to power SO’s plants, thereby reducing waste and expenditures on coal power.

- Raw materials procurement: SO employed its own crude buying agents rather than using independent contractors like its competitors. SO also built an extensive network of warehouses to hold extra oil in case prices unexpectedly spiked. Eventually, SO developed its own sources of crude to ensure constant, cheap supply.

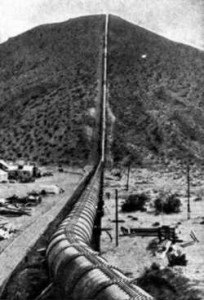

- Raw materials transportation: Crude was traditionally transported in wooden barrels. Given the high cost of barrels, SO purchased forest land and harvested the wood. SO also pioneered the process of treating the wood in a kiln to prevent leaking. SO later lowered costs even further by investing in tanker rail cars, which at the time were a fairly new invention. Eventually, SO built pipelines to transport crude directly from production sites to the refining facilities.

- Reduction of freight rates for kerosene: SO negotiated reduced rates with the railroad companies in exchange for guaranteed volumes (this solved the aforementioned problems that railroads had of having to make stops at multiple refiners), thus creating (or at least instituting on a large scale) the concept of volume discounts.

The Results

In 1870, when SO was formed, the price of kerosene was $0.26 / gallon; by 1880, SO had driven the price down to $0.09 / gallon; the price was further reduced to ~$0.07 per gallon by 1890. While SO was highly profitable at these prices, many of its competitors either went out of business or sold themselves to SO. Thus through its competitive operating advantages, scale, vertical integration, continued innovation, and M&A, SO achieved a 90% market share in the refining market which it maintained for over 20 years.

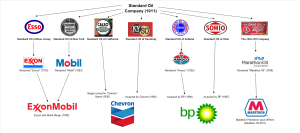

The Legacy: Creation of the Modern Oil Company

Although SO was eventually broken up by the U.S. government in 1911 due to a ruling that it had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act (which actually had to be expanded in breadth to beat Standard Oil), many of its successor companies became some of the largest modern energy companies (e.g. Exxon and Mobil, now ExxonMobil; Chevron; Marathon; and Amoco, now part of BP). Furthermore, the operating model that Standard Oil pioneered is still largely the model used by modern integrated oil & gas companies today and which allows for affordable energy production.

Sources:

1. https://www.theobjectivestandard.com/issues/2008-summer/standard-oil-company/

2. http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1998/06/08/243492/index.htm

3. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=zaYZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en_GB&pg=GBS.PR7

4. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~twod/oil/NEW_SCHOOL_COURSE2005/articles/research-oil/john_mcgee_predatory_pricing_standard_oil1958.pdf

5. http://corporate.exxonmobil.com/en/company/about-us/history/overview

6. http://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/jd-rockefeller.asp

7. http://www.history.com/topics/john-d-rockefeller/videos/rockefellers-standard-oil

Its amazing that vertical integration and efficient utilization of resources could lead to such a strong leadership position in the market (90% share). I did not know that the antitrust legislation was introduced because of SO. Very interesting post!

Nice write-up, Schultz. Thought the breakup graphic at the end was cool – explained what all those Esso (Ess… O… Standard Oil) stations that we saw in Montreal a few weeks ago were.

Josh – Not going to lie, your catchy tag line drew me in. But I totally agree with the assessment and find the rise of Rockefeller with SO to be incredibly interesting. It’s incredibly counter-intuitive to think they became incredibly profitable by decreasing the price of their product to 1/3 the original price but the impacts on competition seem to speak for themselves. Another point to think about as that they started the use of pipelines to transport oil which further decreased costs as railroads became more expensive.

I think this is the only section D post that looked at the business model vs operational model question of processes that happened so far in the past. In many ways, we’ve spent the latter part of the semester looking at more contemporary hi-tech operations management and this post implemented all of that on a fascinating 19th century operational problem. I’d wonder if you think that breaking Standard Oil up into its many successor companies — most of which, eventually became incredibly powerful — means that the Sherman act actually helped/forced SO to continue to innovate and adapt. I wonder what are the incentives to innovate further if you had already achieved a 90% market share. (But that might just be the Elizabeth Warren fan in me talking.)