Should Tesla Buyers Receive Tax Subsidies from the Government?

In the US, individuals purchasing a new electric vehicle receive up to $7500 in tax credits (many states add additional incentives). What is the government trying to accomplish with these tax credits? Who should qualify? How might we analyze the efficacy of the programs?

The United States government has a long history of providing tax incentives to encourage desirable individual behavior. Classic examples include tax breaks for owning a home, paying for employee health insurance, and making long-term capital investments. We can judge the merits of incentive programs on two primary dimensions: the beneficial side effects the behavior creates for the rest of society (positive externalities), and the reduction of economy inefficiency that might occur in a free market (deadweight loss). Similarly, we can criticize tax incentives that do not provide sufficient benefits in comparison to the cost: lower than expected positive externalities, an undesired distortion in individuals’ behavior, or an unintended participant capturing a majority of the benefits.

For example, various complex government policies lower the effective cost of borrowing money to buy a home. In theory, higher home ownership stimulates job creation and tends to improve the surrounding neighborhood. On the other hand, the same policy might encourage consumers to take on high-leverage, risky loans. Rising housing prices may form or fuel an asset bubble that can wreak havoc on the economy at a future, inconvenient time. The improved return on investment may invite speculators who buy multiple homes and operate illegal hotels.

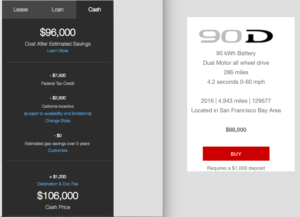

Back to electric cars, Exhibit 1 shows a screenshot of the ordering page for a typical new Tesla Model S. The top price shown is actually the “Cost After Estimated Savings” price. Only after more careful examination below do we see the cash price.

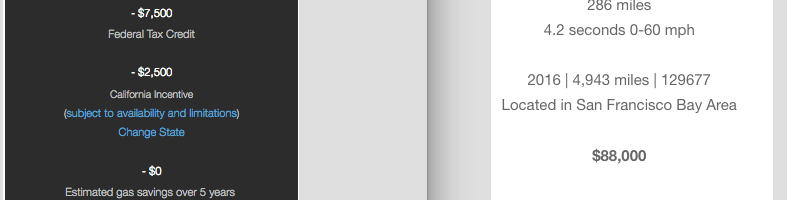

Tesla also sells certified pre-owned cars (not eligible for tax credits), which carry generous manufacturer warranties of 4 years and 40,000 miles. Exhibit 2 shows a very lightly used vehicle from the certified pre-owned store within the Tesla site, with features that closely match the new vehicle in Exhibit 1. As expected, the used car pricing is a predictable function of the new car price AFTER subtracting tax incentives. Both parties are mindful of the subsidy, but are they the only ones capturing any value? Is the tax incentive a pure transfer of wealth from the public to a luxury car buyer?

The initial goals of electric vehicle incentives are admirable. Americans want to reduce their reliance on foreign oil and encourages the research and development of alternative energy sources. When the first electric hybrids arrived on the market (Toyota Prius), the price was significantly higher than comparable sedans, even after factoring in gasoline savings. The policy aimed to encourage faster adoption of low emission vehicles among price-sensitive consumers.

The tax credit also helped overcome a subtle chicken-and-egg problem from being the first manufacturer to sell plug-in electric vehicles. Early on, there is little demand to build a network of plug-in charging stations, which makes the vehicles less convenient to own, which further reduces demand. By having the government stimulate some initial demand of vehicles and supply of charging infrastructure, the industry can overcome the difficult initial period and later utilize the network effect to accelerate faster diffusion.

Today, we have already reached excellent coverage along most major highways and urban centers. Communities exist that map out entire routes of charging stations so that electric vehicle drivers can travel confidently without worrying about finding a charging location.[5]

Who is really benefiting from the tax credits today? At least for higher end luxury vehicles, the demand should be relatively inelastic, and almost all of the benefits are going to parties that would have transacted without the subsidy. If that were the case, the government should phase out and end the subsidy.

To examine the demand elasticity, one could analyze electric vehicle sales as a function of consumer gasoline prices, expecting a substitution effect as people opt for electric cars when gas prices rise. So far, the limited data is discouraging, with some studies citing 0 correlation.[6] Although we need more robust studies before drawing firm conclusions, my hypothesis would be that many electric vehicles are long past the need for a government subsidy. A Tesla is clearly a luxury goods and the buyer or seller should not receive a public subsidy.

Fortunately, we are seeing some reaction from governments around the world to exclude luxury vehicles from the tax incentives[7]. In the United States, the latest proposal expands the federal tax credit to a maximum of $10,000, except the increase excludes cars with a purchase price over $45,000. That’s an encouraging step, but in my opinion, if the data shows the tax credits no longer serve the right purposes, we should phase out incentives for all electric vehicles as soon as possible. (Word Count 800)

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_incentives_for_fuel_efficient_vehicles_in_the_United_States

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plug-in_electric_vehicles_in_the_United_States

[3] https://www.tesla.com/preowned/5YJSA1E29GF129677

[4] https://www.tesla.com/models/design

[6] https://pluginamerica.org/do-gas-prices-correlate-plug-vehicle-sales/

[7] https://electrek.co/2016/05/06/tesla-excluded-ev-incentives-germany/

Hi Lee,

Very interesting article – you do succinctly point out that tax credits such as those for electric cars and for house purchases (i.e. mortgage interest tax deduction) inherently create “winners” (i.e. luxury car buyers) and “losers” (i.e. the tax payer and other green energy industries that would perhaps benefit more from similar tax breaks). An alternative political approach to spending tax payer money on green energy credits would be to spending tax payer money on developing a national infrastructure for a carbon tax or carbon cap and trade market to naturally create price discrepancies between high carbon and low carbon goods and services in a more precise way. That said, it does not seem that this is in the political cards and perhaps that is why we see a piecemeal approach to the automotive industry and green energy initiatives.

Taki

Lee,

Your post reminded me of another article (http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/17/business/international/norway-is-global-model-for-encouraging-sales-of-electric-cars.html) that describes the even more aggressive electric car subsidy regime in Norway. Due to generous tax breaks and much higher prices for diesel fuel, it is cheaper for a Norwegian to buy an electric car than a traditional combustion engine vehicle. I thought this policy decision was fascinating in a country that produces 1.6 million barrels of oil per day, accounting for 8% of GDP. I am sure this decision was not based on an economic cost-benefit analysis, but rather on a value-based interpretation of the role of government in shaping consumer preferences. Concerns about climate change and sustainability cannot be easily internalized at an individual level to account for all inter-generational externalities. That why I think there might be a role to play for governments to direct some of those choices, despite short-term costs.

-Patricia

Wonderful stuff Lee; I thoroughly enjoyed reading this. It seems the issue lies with the cost of manufacturing these vehicles. Tesla appear to be hamstrung in their ability to offer cheaper alternatives to the ’90’ without compromising on design and performance with an electric engine. Would it make more sense to offer R&D subsidies or patents similar to those of the pharmaceutical industry? If affordable, high-quality alternatives exist, then we may see many more electric/hybrid vehicles on the road in the future.

Interesting point, I agree that if elasticity truly is 0, then these subsidies are difficult to justify.

I do think there is another positive externality besides developing a national charging network. The automotive industry has a massive minimum viable scale, and the cumulative experience from manufacturing internal combustion engine vehicles has helped drive costs down while improving performance for decades. This presents a very tough climate for a new technology, which cannot immediately achieve the same scale, and requires reinvestment economics in order to improve the technology and manufacturing processes for an electric vehicle. By starting with a smaller market (luxury sedans), Tesla has been able to ramp up production, refine it’s manufacturing, and improve electric vehicle technology as it prepares to launch the mass-market Model 3.

Great piece, Lee. Aces, as usual. Looking further into this issue, I think we should tease out the price elasticity of demand for luxury vehicles. While I agree that luxury goods are generally inelastic, I believe the price of a Tesla luxury vehicle is more elastic than other types of luxury goods for two reasons. First, in my opinion, luxury vehicles are the most aspirational luxury goods available (partially because of the easy financing available that is otherwise not for say, a Rolex or Prada), and I think most of us have known people at various points in our lives who aspire to own a really nice car, even if they’re eating ramen noodles every night to do it. Second, the basis of luxury good price inelasticity of demand is largely that those who have large disposable income are less likely to consider price as a factor because they have a large amount of income to dispose on a number of goods and services that a person might want. I think that makes sense when you’re talking about a purse. However, my instinct is that Tesla buyers are relatively well-informed consumers, and cars, unlike most other luxury goods, can be evaluated on a wealth of quantitative data (0-60 time, horsepower, torque, car magazine ratings, top speed, mpg, warranty, resale value, etc.) and price is a factor which a sophisticated consumer might measure the efficiency of his/her dollar when performance characteristics are otherwise similar. As a luxury sedan, Tesla Model S’s also have a “cool” factor that grandpa’s Audi A8, BMW 7-series, or Mercedes S550 does not. Price may be the straw that breaks the camel’s back in those otherwise tight races.

I agree with your analysis, but I think there is some room for a subsidy to work on an electric car, especially when compared against other luxury gas-guzzlers. The dollar amount, however, is another story. $7K may not move the needle enough to be relevant at a $100K MSRP versus a $50K MSRP, and anything larger may not be affordable to the taxpayer.

Lee, this interesting post prompted me to do a bit of additional reading about tax credits for electric vehicles. One interesting point made by the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (https://www.cbo.gov/publication/43576) is that these tax credits have so far probably not reduced overall gasoline consumption or emissions from vehicles. The reason is that automakers must already comply with CAFE standards, which govern the average fuel economy of cars sold by a particular manufacturer. If the automaker sells more electric cars, it can also sell more higher-emission cars – and still meet the average fuel economy standard. However, over the longer term, increased sales of electric vehicles (spurred by tax credits) could lead to more stringent CAFE standards, so the tax credits could still have a positive indirect effect in the years to come. CBO recognizes that a much more direct approach to reduce vehicle emissions would be to raise the federal gas tax, which has not been increased since 1993. Congress did not opt for this approach when it passed a surface transportation reauthorization bill in late 2015.

Lee, interesting posts. Three counterpoints come to mind:

1) I’m not convinced that Teslas are as inelastic as you’re suggesting. If that were the case, in theory Tesla could charge an extra $10k ($116 instead of $106k) for their car and make more profit but there would be no corresponding change in quantity.

2) Even if luxury car buyers are more price inelastic, I think there’s also a psychological side where you’re more likely to buy the car if you think you’re getting a car that’s really “worth” $106k for the price of $96k

3) On the flip side, if Tesla is capturing the value of the subsidy (by selling a $96k car for $106k) instead of the consumer, then the tax subsidy would also help encourage companies to produce more electric vehicles because they could charge consumers a higher price for the same value car.

Interesting read Lee. I thought one additional point about Tesla that showcases their true commitment to sustainability is releasing their patents to the world in 2014 (https://www.tesla.com/blog/all-our-patent-are-belong-you). The fact that the company actively wants other companies to work on electric zero emission vehicles is refreshing.

I would love to hear your thoughts on whether the tax subsidy would be relevant for a non-luxury vehicle such as their upcoming Telsa Model 3.

Lee,

Not surprised to see you posting about Tesla, and good work coming in at exactly 800 words on the post. I typically would agree with your point that subsidizing luxury cars is mostly useless, but if a subsidy can move a car from one cost bracket to another, it could have a real effect on behavior. The government has a chance to drive innovation here. If it were to introduce a tax credit only applicable to cars prices under $35,000 then I think it would have both an effect on manufacturer and consumer behavior. The manufacturer would have a heavy incentive to manufacture a car under $35k and the consumer would also be incentivized to buy. This could really change the market.

Lee, an interesting perspective on Tesla and clean energy credits. I agree that they solve the initial fixed-point problem of investing in a new capital intensive market but should be phased out as the market comes to maturity. At this point, Tesla has gone beyond proof of concept and become a desirable luxury brand for many around the world. Therefore, the tax credits provided for buying such a product is unneccessary and should be removed as it only benefits the buyer and puts a higher tax burden on lower income families who are already unable to purchase luxury cars. Instead, the government should promote public research that will lessen the time taken to develop competing technologies and thereby promote rapid expansion and competition in this market.

Interesting point on the structuring of tax incentives to induce consumer behavior, however, I would have to disagree on phasing out the tax incentives for electrical vehicles. When Tesla was first founded at a time when electric auto industry was still nascent, it had a really difficult time seeking equity investments and convincing the public that electric vehicles can both a) match gasoline-vehicles in performance and b) effectively serve environmental purpose. However, as R&D picked up in the space, Tesla joined the ranks of a few pioneers in the industry to shift public opinion towards becoming environmentally conscious. Even if consumer demand for Tesla cars is inelastic, it still does not negate the fact that the company serves a critical social purpose, at the same time offer utilitarian benefits to its users. Intentions differ, sure, but results remain the same, and while one may argue that the tax incentives should be allocated elsewhere, I think eliminating these incentives would have significant signaling effect to rest of the industry, and may deter a significant number of marginal consumers that are considering investing in electric cars overall.

Interesting article!

I agree with the premise that luxury electric car companies should not be the ones receiving the subsidy as demand is clearly inelastic for luxury electric car vehicles. Moreover, the subsidies can be more efficiently used to support electric car companies working on making electric cars available for the masses, not the few rich!

One can also make an argument that subsidies are not the most efficient way to change behavior. The most powerful tool to change behavior is to create an ecosystem that is able to develop innovative, efficient products for the masses at affordable prices. I would argue the government would be better-off investing in venture capital companies supporting startups that are innovating in this space.

Many of you have convinced me to rethink the harsh cries for an immediate end to the subsidy. After reading through comments, the primary takeaway is to try to research the true elasticity of demand, and in particular stay mindful of likely substitution effects to competing cars. I have always found the range of Tesla buyers to be an intriguing mix of three different categories: the car enthusiast, the luxury environmentalist, and the tech geek (autopilot hobbyists fall into this category). Speaking as a member of the final group, I had thought there was no substitution effect on demand because there is no other way for a consumer to purchase a self-driving car. However, you’ve all convinced me that the generic fast-car, “Ludicrous Mode” enthusiast does have other viable options in which $7500 can tip the scales.