Reforming Retail: Reformation’s Fashion-Forward Approach to Sustainability

Fast fashion retailer Reformation wants to be the “Tesla of Clothing” — both innovative and environmentally conscious. But can this small company succesfully clean up the apparel industry?

The apparel industry has a dirty secret: Its supply chain innovations and rapid growth are devastating the environment. Fast fashion startup Reformation is disrupting the status quo by becoming the “Tesla of clothing”— a white-hot brand that happens to be environmentally friendly. It remains to be seen if its tactics will work at scale.

Quick & Dirty Fashion

Global clothing production doubled from 2000-2014 [1] and is expected to rise an additional 63% by 2030 [2]. Rapid industry growth has been fueled by increased consumer spending and the rise of “fast fashion,” an innovation in clothing production that shortens the time required to bring styles to market. For example, mega-retailers Zara and H&M each offer between 12-24 clothing collections per year, compared to 2-4 seasons offered by traditional retailers [3].

These trends result in massive waste from producers and consumers alike. The apparel supply chain consumes significant water, chemicals, and fossil fuels; for example, the production of 1 kilogram of fabric generates an estimated 23 kilograms of greenhouse gases. On the demand side, consumers now cycle through 60% more clothing per year and keep each item for half the time than in 2000 [4].

As seen in the figure below, these practices will have a significant incremental impact on the environment by 2030 [5].

Reforming Today

L.A.-based retailer Reformation attempts to (literally!) reform these wasteful practices. Since its founding in 2009, the company has drawn inspiration from electric car maker Tesla by emphasizing both environmental friendliness and cutting-edge design. In particular, Tesla inspires two key tenets of Reformation’s strategy [6]:

(1) Put great products first.

The motto says it all: “Reformation [makes] killer clothes that don’t kill the environment.” The company sells edgy, fashion-forward pieces created from sustainable fabrics: Over 50% of its garments are made of Tencel, Viscose, and recycled materials, which consume less water and other resources than cotton, and another 15% are made of vintage or deadstock fabrics that would have otherwise gone to waste [7].

The company also sits firmly within the fast fashion category, bringing new styles from concept to stores in one month and using analytics to inform merchandising decisions (for example, new products are initially manufactured in small batches, with production expanded if they perform well online) [8]. However, Reformation is significantly more sustainable than its larger peers due to a vertically-integrated supply chain. The company manufactures 70% of its products in its wholly-owned Los Angeles factory [9], a 33,500 square-foot building that houses design, manufacturing, and fulfillment operations under the same roof [10]. This facility is powered by renewable energy, and Reformation purchases offsets to remain fully carbon-neutral [11].

While the company did not initially offer details of its eco-friendliness, it is increasingly educating consumers via its website and social media channels. Product pages now include a “RefScale” rating, an internally-generated score (verified by a third party) calculating the per-item water usage, CO2 emissions, and waste relative to a comparable product from a competitor [12].

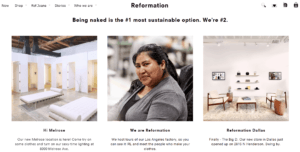

(2) Reimagine the in-store experience.

E-commerce remains the heart of Reformation’s business, but the company’s long-term objective is to build out a complementary brick-and-mortar presence (it has opened 8 stores to date). Inspired by Tesla’s retail locations, Reformation maintains a simple in-person shopping experience that supports its sustainability goals. For example, each store minimizes the number of items it has on the floor to reduce clutter and inventory wastage. To do so, Reformation only offers its most successful items based on online purchasing activity, as 80% of sales come from 30% of its SKUs [13].

In February 2017, the company opened its first next-generation store in San Francisco, supported almost entirely by technology. Shoppers use a touchscreen mirror to order items, which are delivered directly to the dressing room through a magic wardrobe. Reformation utilizes the order data on the back end to track the number of store visitors and SKU performance, further improving its inventory management [14]. The company expects to open additional technology-enabled stores going forward.

Reforming Tomorrow

Reformation’s desire to scale will put pressure on its sustainability mission. The recent launch of Ref Jeans illustrates this tension: The company is outsourcing production of jeans — an environmentally destructive type of clothing, with 1,500 gallons of water used per production cycle [15] – to a third party. Management should view this step as an opportunity to educate the industry in its best practices, but it should also invest in tools and technologies to ensure compliance and tight supply chain management

Other questions:

(1) How should Reformation further engage its consumers in promoting sustainability? For example, only 20% of clothing globally is recycled [16]. Can or should the company launch a recycling program?

(2) While the RefScale is a meaningful step towards introducing transparency to fashion retailing, are there better ways to communicate this information? Should Reformation push the industry to adopt a single standard?

(Word Count: 796)

Sources

[1] Nathalie Remy, Eveline Speelman, and Steven Swartz, “Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula,” October 2016, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability-and-resource-productivity/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula, accessed November 2017.

[2] Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group, “Pulse of the Fashion Industry,” May 2017, p. 8, https://www.copenhagenfashionsummit.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Pulse-of-the-Fashion-Industry_2017.pdf, accessed November 2017.

[3] Remy, Speelman, and Swartz, “Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula.”

[4] Ibid.

[5] Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group, “Pulse of the Fashion Industry,” p. 10.

[6] Elizabeth Segran, “Can Fast Fashion Be Ethical? Reformation is Rewriting the Rules,” February 9, 2017, https://www.fastcompany.com/3067776/can-fast-fashion-be-ethical-sustainable-reformation-is-rewriting-the-rules, accessed November 2017.

[7] Reformation, “Our Stuff,” https://www.thereformation.com/whoweare#fabric, accessed November 2017.

[8] Tracey Greenstein, “Sourcing Is Key to Reformation’s Ethical and Sustainable Manufacturing,” August 3, 2017, http://wwd.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/business-news/technology/the-reformation-sustainable-manufacturing-10955994/, accessed November 2017.

[9] Hilary Milnes, “‘Mannequins freak me out’: Inside Reformation’s new techie San Francisco store,” February 14, 2017, http://www.glossy.co/store-of-the-future/mannequins-freak-me-out-inside-reformations-new-techie-san-francisco-store, accessed November 2017.

[10] Greenstein, “Sourcing Is Key to Reformation’s Ethical and Sustainable Manufacturing.”

[11] Reformation, “Sustainable Practices,” https://www.thereformation.com/whoweare#refscale, accessed November 2017.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Milnes, “Mannequins freak me out’: Inside Reformation’s new techie San Francisco store.”

[14] Kari Hamanaka, “Reformation to Bow in San Francisco With Tech-Savvy Space,” February 13, 2017, http://wwd.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/business-news/retail/reformation-to-open-tech-savvy-san-francisco-store-mission-district-10799114/, accessed November 2017.

[15] Hilary Milnes, “How Reformation tackled faster, affordable denim sustainably,” October 24, 2017, http://www.glossy.co/sincerity-sustainability/how-reformation-tackled-faster-affordable-fashion-sustainably, accessed November 2017.

[16] Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group, “Pulse of the Fashion Industry,” p. 59.

I have to say upfront that I know nothing about the fashion industry/supply chain, but I know enough to be dangerous in a conversation about Tesla. I think what Reformation is doing is very admirable and I hope they can continue to grow. Two things stand out when comparing to Tesla’s situation a few years ago: 1) The Model S was a vastly superior product that people were willing to pay a huge premium for, and 2) Tesla had a clear path to bringing the cost down because of the relative immaturity of electric vehicle/battery technology. It seems Reformation has that superior product that at least some subset of the population will pay for, but moving down the cost curve might not be as easy. Nothing in their operations screamed “opportunity to reduce costs by 60-70%” to me, but like I said, this is far outside of my domain. Maybe prices will be fine where they are for a while, but it seems like Reformation eventually wants to reach a much wider customer base and needs to bring costs down accordingly. With cost in mind, I would hesitate to introduce new programs, such as recycling. At a certain point, consumers need to be responsible on their own and not rely on Reformation. Perhaps a recycling education tag on their clothes would be a cheaper way to inform an already environmentally-conscience consumer of the importance of proper disposal. Finally, I would like to see them change their RefScale to a more meaningful metric. Just providing a quantitative comparison to a very inefficient process is not enough. At the very least, I would like to see a percentage reduction rather than just saying “2 gallons less.” I would also like to see them try to start a movement for industry standards, but that is quite an ask for a company at their stage/size.

While I know little about Tesla or retail from a supply chain perspective, I do have some experience as a consumer and some perspective to offer on these questions from my experience working at a disruptive healthcare company. From a retail perspective, my biggest concern is whether the quality of the clothing is on par with less sustainable brands. Other than that the clothes are eco-friendly I find the comparison with Tesla difficult since from what I can tell they don’t seem to be truly innovating on styles or offering the highest quality products. I took a look at some of their customer reviews, and they seemed fairly split between customers who love the brand and those who were frustrated by low quality garments that shrunk in the wash. While these reviews often represent the most extreme viewpoints, it does make me somewhat concerned about their ability to scale and compete with high-end retailers on quality, not just sustainability. This is especially important given the relatively high price point these clothes are sold at since, as Grant mentioned, for this model to work customers need to be willing to pay a premium to cover the margins associated with the company’s sustainable approach.

I agree with Grant that they should change their metrics to be more specific. From my experience in healthcare I also learned that it can be effective to call out your competitors on their waste. My previous employer, athenahealth, started posting metrics on its site comparing athena’s ability to help physicians meet quality measures to that of its competitors. While athena did not initially beat its competitors by very much, this transparency provided motivation for both athena and its competitors to improve. While Reformation is implicitly calling out the rest of the industry for its unsustainable practices, I think they could take a broader stand in trying to transform the industry at large through transparency. This could include information either about specific companies that are doing the most harm, or providing general metrics about the industry’s waste to increase awareness on this topic.

Thank you for the great essay, Lawren! It is a very interesting topic as I think about this change is related not just to business decisions of the companies, but also related to changing general public’s attitude about fashion and lifestyle. It reminds me of the Japanense brand “Muji”, which is famous for its simple yet elegant design as well as quality products. They have beautiful stores as well where one can feel a strong sense of simplicity walking into them. Such idea of having a simple life is deeply rooted in Japanese culture and has become a strong trend even within Chinese young customers. Keeping only few quality things that are essential to life has become a fashion or even lifestyle statement by many young people in Japan or China.

I do see the potential to make this change in customers in other markets as well. But I personally think new brands, such as Muji, rather than the existing fast fashion brands will have more incentive to push for this trend, as they usually charge a price premium for quality products to compensate for less volume, which makes their business case viable.

Lawren, great essay! Really interesting and a topic that I’ve thought about a lot given my interest in retail. I agree with Grant’s point above that it’s difficult to know how much Reformation has a superior product that justifies the cost and that really attracts customers. Is the sustainability piece of reformation enough? I think an interesting comparison will be with Everlane. They just launched a line of jeans and did a lot of press about how clean and sustainable their factory is (https://www.everlane.com/denim-factory). Reformation seems to have a similar story and a similar aesthetic in their clothing, so I’ll be interested to see what happens with both companies.

To your questions around adopting a single industry standard – I think that absolutely needs to happen. Given how remote and unclear the supply chain of clothing is to the average consumer, people who are looking for “ethical” clothing are often stuck either trusting the PR of a corporation or doing extensive research. Particularly for consumers who are looking for more upscale/trendy clothing, the options can be limited! I wonder how Reformation can lead the way in trying to adopt industry norms around what is “ethical” or “sustainable” as more of a wide-ranging rating system. I would guess there would be significant pushback against an industry-wide standard, but do believe it’s important and wonder if Reformation would have the ability to lead the way.

I think you hit the nail on the head when you described Reformation as “a white-hot brand that happens to be environmentally friendly”. This is a key distinction for companies that want to source items sustainably–as much as consumers talk about wanting to be environmentally friendly, they aren’t as willing to sacrifice fashion or price to get there. I think that both Tesla and Reformation have this figured out–their primary value proposition to the customer is encapsulated in the product, and the experience that comes with the product, with sustainability an ancillary benefit to the consumers. I think this raises the bar for suppliers that want to be environmentally responsible–they need to prove that they can be just as fashionable and just as profitable as any other company, even while practicing sustainable sourcing.

Speaking as an avid Reformation consumer, I loved learning more about their efforts to lead the market in sustainable fashion. I think GF’s point above regarding the parallel to Everlane is super relevant here in regards to how Reformation might successfully communicate their internal efforts to their external audience – in a way that doesn’t dilute the simplicity and elegance of the brand. Everlane’s mantra of “radical transparency” aims to shift not just the way that consumers shop for Everlane, but the types of questions consumers ask when shopping for anything, anywhere (e.g. how much is this actually marked-up and why?). Everlane leverages their online platform as a mechanism for education by presenting its customer with videos, images, and behind-the-scenes visibility into sourcing and pricing decisions that a brick-and-mortar store just can’t accomplish. In that regard, I think Reformation has a huge opportunity in leaning on its online-first model to offer the customer more learning opportunities alongside an e-commerce experience. By bringing customers into the fold as to how Reformation is investing in higher quality, sustainable prices, the brand can drive customer loyalty and higher willingness-to-pay – and place increasing pressure on the industry as a whole.

One question I leave with is how customer attitudes might shift if the economy takes a hit. Right now, customers might be able to afford paying a premium for a sustainable product, but will they shop with the same commitment to values when financial pressures increase? Pushing for industry standards in anticipation of such ethical elasticity could be very smart!

I take a positive view on this strategy and will argue that a retail brand doesn’t need to go down a cost curve like Tesla because the industry economics are different. Gross margins in retail are inherently high and increase proportionally with price point increases because people pay for intangible promises like “brand” and “fashion”. R&D is significantly lower to the point of non-existent and because Reformation is a direct-to-consumer brand they don’t give up margin to whole sellers and retailers. Granted, they need to invest in Marketing and SG&A, however, they can do so at their own pace versus aiming at satisfying a retail store in terms of price and supply, thus effectively negotiating how much they discount. Reformation is positioned higher (@ $200+ for a dress) than fast fashion brands like Zara and Mango, so I’m not worried about their profitability prospects in the near term. My concern would be with quality and as some consumer would be unwilling to pay a premium for a brand that offers an inferior product even if that product is environmentally save.

Super interesting! Whenever I’ve thought about climate change, fashion has never entered my head. Some quick googling has quickly made me realize how wrong I’ve been; fashion is the 2nd largest polluting industry globally! I agree with your worries about the difficulties they’ll face as they begin to seriously scale. Something they might consider as they take this journey is to emulate brands like Primark who have a number of sustainability initiatives currently:

https://www.primark.com/en/our-ethics

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/primark-sustainable-cotton-line_uk_5989cf67e4b0449ed50592f2

Loved this essay. A great case study on a highly relevant company that raised some fascinating questions.

I would like to focus on Reformation’s proposition of scaling their network of physical stores, and argue that it is a high-risk strategy. When digital-first companies do this, they come from one or more of a few perspectives. I will posit that none of these are a plausible enough reason to employ the strategy. If they want to build a long-term platform for their sustainable practices, they should limit their offline sales, for now.

1. To ‘revolutionize’ the shopping experience: they want to bring some of their online expertise to reinvent the shopping experience in a new and improved way.

This is misplaced. In Christensen’s terms, their brick-and-mortar improvements are ‘sustaining innovation’ (as opposed to ‘disruptive innovation’), and they will be unlikely to provide a better experience than their retail peers. An attempt to ‘beat retailers at their own game’ is unlikely to succeed. Traditional retailers will be more competent at retailing, and the demand-side synergies between online and offline presences look overstated. Amazon’s physical bookstores are an example of this. Their competency is building a logistics network and online product offering, and their brick-and-mortar experience, although ‘revolutionary’, has been poorly reviewed. Christensen’s research follows that, in Reformation’s case, the ‘magic wardrobe’ and ‘touchscreen mirror’, if effective, would likely already have been scaled by existing retailers.

2. For brand awareness and credibility: the ‘concrete billboard’ strategy.

If brick-and-mortar stores are simply a marketing channel to drive online sales, they should be wary of the high fixed costs and inflexibility of scaling their stores. There will likely be diminishing returns to number of stores, and their customer acquisition cost will far exceed their lifetime value. As purely a marketing plan, the economics are unlikely to work, and they could likely scale their practices (business and sustainability) by focusing on the online channel.

3. As an additional sales channel: they aim to steal more share from brick-and-mortar competitors simply by taking customers who prefer in-person shopping.

Reformation should consider that there is a lot of room to grow online at a higher margin. Although in-person retail is a much larger market, the market is far from fully penetrated, and they likely get better returns from allocating their capital to scaling the online channel through marketing, for now at least.

In all, although Reformation’s environmental practices may be market-leading, their very sustainability could be more sustainable without pursuing brick-and-mortar retail.

I struggle with Reformation’s positioning, because I can’t get past the simple question: Can you call yourself a sustainable company when you are intentionally creating fast-fashion products?

While I think the transparency elements they’re introducing to their UX experience are helpful to make sustainability top of mind for the consumer, I’d argue they are not undertaking anything revolutionary in their supply chain to warrant the positioning of a “sustainable business”. In fact, I would argue that their entire angle is simply to try and offset their company positioning of consumable goods. These are not clothing items that are meant to be kept for a life-time. They are a slightly better version of Zara, but is that enough of a pedestal to stand on?

I struggle to see any altruistim in their sustainability claims, and they seem to have self-selected those that also benefit the business from a profitability perspective. Using materials such as Viscose are noticeably cheaper than the material alternative of silk, and carrying little inventory in stores is a profitability play, not a sustainable one.

I agree with you that they should be taking the sustainability angle one step further and offering services that will actually push the industry as a whole to approach it differently. When that is accomplished through things such as a recycling program, than I can say confidently that they’ve played their role to help identify and alter the direction of other companies.

A very interesting article, thanks Lawren. Environmental sustainability is Reformation’s top customer promise since its establishment, which is great but also challenging for a fast-fashion company because it cannot pass higher upstream raw material costs to end-customers as easily as a luxury apparel company might do. As what we learnt from IKEA case, from long-term perspective, it is important to find a way of absorbing additional costs attributed to environmental sustainability without eating up margins nor increasing end-user prices. In my opinion, technology innovation of raw material production is also crucial.