Modern Meadow: Using Additive Manufacturing to Reimagine Fashion and Food

Biofabrication has the potential to radically change how we obtain, process, and transform animal products for food and fashion.

Background

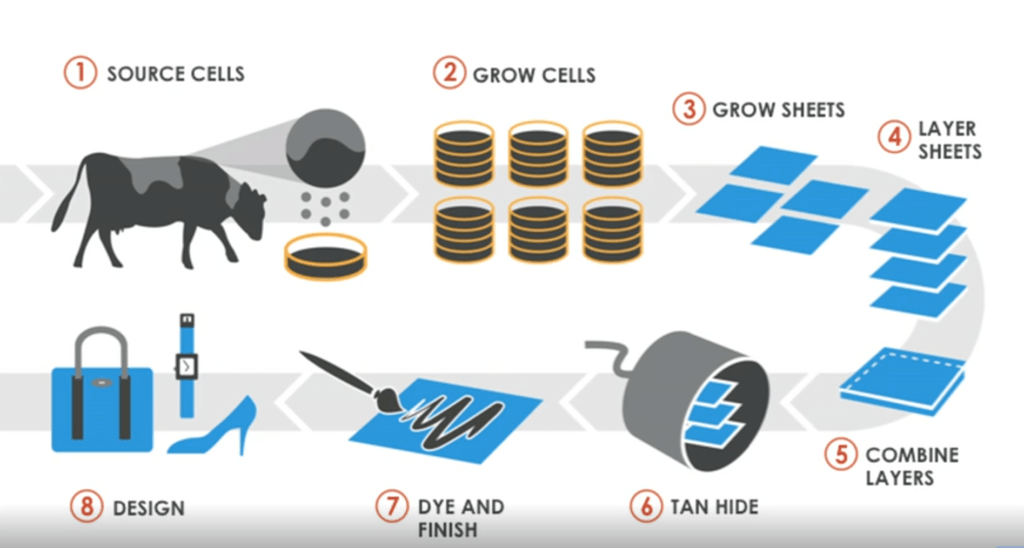

Modern Meadow was founded in response to a simple question: “if you can grow human body parts, can you also grow animal products, like meat and leather?”[1] The underlying process, known as biofabrication, essentially utilizes 3D printing technologies to engineer biological products, such as tissues and organs, using the same foundational cells that comprise them in nature[2].

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), “livestock production plays a critical role in land degradation, climate change, water and biodiversity loss”[3]. Grazing alone occupies 26% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, and feed-crop production requires a further 33% of all arable land[3]. The livestock sector accounts for 9% of global carbon dioxide emissions, 37% of global methane emissions, and 65% of global nitrous oxide emissions[3]. Conventional production of animal products place the environment, public health (due to animal-borne diseases), and food security at risk, all of which are expected to be further stressed as the global population increases over time.

Right now we breed and raise highly complex animals only to create products that are made of their relatively simple tissues. Andras Forgacs, the founder of Modern Meadow, argues that this is not only cruel to slaughter animals, but also potentially inefficient from an energy conversion perspective as it would take far fewer resources to grow the desired cells/tissues than to grow entire living, breathing animals[1]. Focusing on biofabrication of animal products may present a humane, environmentally responsible, and efficient alternative to conventional production methods and Modern Meadow is one of the few funded labs tackling this solution via entrepreneurship.

Current Strategy

Growing leather is technically simpler than growing other animal products (such as meat), as it mainly uses one cell type and is largely two-dimensional. It is the belief of Modern Meadow that until biofabrication is better understood by the public, more people would be willing to wear novel materials than would be willing to eat novel foods, no matter how delicious they are[1]. Modern Meadow views bioleather (which they have launched and branded as Zoa[4]) as a gateway product, the success of which may potentially open the door to long-term, mass-scale food production using biofabrication.

Modern Meadow has refined its approach using a bio-engineered strain of yeast that, when fed sugar, produces collagen, which is then purified, assembled and tanned to create a material that is biologically – and perceptibly – almost indistinguishable from animal leather[5]. This bioleather can have all of the same characteristics of animal leather because it is made from the same cells, but bioleather has a variety of distinct manufacturing advantages over animal leather. Bioleather eliminates the possibilities of imperfections (i.e. scars, disease, etc.) that are often associated with living animals due to the controlled growing environment, while the sheets themselves can be grown in any shape or dimension (i.e. you no longer have to work within the dimension of an animal-hide), both of which dramatically lower waste during production. Unlike conventional methods, Modern Meadow has control over both the specific cells selected and the number of layers it chooses to combine, which in combination can dramatically influence the characteristics of product development (i.e. transparency, softness, breathability, durability, elasticity, pattern, etc.). Operationally speaking, bioleather has the potential to reduce variability and cost of input materials while decreasing waste and simplifying the supply chain, all of which would improve performance.

Recommendations

A few major fashion houses (notably Hermès, Prada, and Gucci) have taken a keen interest in funding tech companies to grow leather in laboratories to ethically source exotic materials (i.e. crocodile-skin) for their luxury labels and feel that the speed of technological advancement could soon result in a viable product[6].

I believe that Modern Meadow is making a mistake by trying to bring a finished good to market within the next 2 years[5], as it only has a competitive advantage in the production of bioleather, not the downstream production of handbags. In my opinion, their goal should be to prove that their bioleather is of comparable quality to animal leather as soon as possible so that they can partner with the major fashion houses who can produce goods for the end consumer with the immediate benefits of scale.

Open Questions

Is the company’s time better spent on replicating exotic leathers or traditional cow leathers? What would it take for consumers to become comfortable with eating biofrabricated food?

(724 words)

[1] Chung, B. (2018). Would you eat 3D-printed meat? 7 vegetarians and vegans reflect. [online] TED Blog. Available at: https://blog.ted.com/would-you-eat-3d-printed-meat-7-vegetarians-and-vegans-reflect/ [Accessed 13 Nov. 2018].

[2] Horch RE, e. (2018). [Biofabrication: new approaches for tissue regeneration]. – PubMed – NCBI. [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29378379 [Accessed 13 Nov. 2018].

[3] Stanford University. Harmful Environmental Effects Of Livestock Production On The Planet ‘Increasingly Serious,’ Says Panel. Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/02/070220145244.htm [Accessed 13 Nov. 2018]

[4] Zoa.is. (2018). ZOA™ | Grown by Modern Meadow™ – Introducing ZOA™ bioleather materials. [online] Available at: http://zoa.is/ [Accessed 13 Nov. 2018].

[5] Alexei Kansara, V. (2018). With Lab-Grown Leather, Modern Meadow Is Engineering a Fashion Revolution. [online] The Business of Fashion. Available at: https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/fashion-tech/bof-exclusive-with-lab-grown-leather-modern-meadow-is-bio-engineering-a-fashion-revolution [Accessed 13 Nov. 2018].

[6] Dalton, M. (2018). Fashion Labels Scramble to Shed Their Skins. [online] WSJ. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/fashion-labels-look-to-be-cool-by-being-less-cruel-1532005200?mod=searchresults&page=1&pos=1&ns=prod/accounts-wsj [Accessed 13 Nov. 2018].

Great article on how 3D printing can be applied in ways to help save the environment. I would say that Modern Meadow’s time is better spent on traditional cow leathers, at least at first – it’s used in many more products (shoes, wallets, belts, etc.) and wide consumer exposure to bioleather versions of these common products would help bioleather gain acceptance. Also, exotic leathers are probably prized in part because they came from an exotic animal – those buyers probably want the imperfections because they prove that the leather is from a ‘real’ source.

Getting consumers to be comfortable with biofabricated food could be very tricky (it could suffer a similar backlash as the one against GMOs). One idea might be to initially channel it through some avant-garde restaurants as a novelty food, then allow word to spread of how it’s just like the ‘real’ thing, and expand the market from there.

I really enjoyed learning about an “unconventional” approach to 3D printing. I share the same question about the average consumer’s perception of “real” vs biofabricated leather. The introduction of biofabricated leather may actually drive up the price and prestige of the “real” leather as it could appear to be more scarce and authentic, leading to a potential increase in demand. The same thing could happen for meat or other biofabricated foods. Another question I would have is around differences in quality of biofabricated foods. Is it possible to have different grades of food – similar to categories of steak houses – that would determine which consumers would be more willing to adapt?

This is fascinating topic! I completely agree that Modern Meadow should not produce a finished good but that they should rather position themselves as a supplier for luxury brands. In addition, I think that the focus should be on high end luxury leathers that are currently very controversial. For instance, many luxury brands are being very careful with the use of crocodile leather and are promoting ostriches leather as an alternative.

On the other hand, I am skeptical when it comes to biofrabricated food.In an era where customers are looking for more natural foods (e.g. with the boom of organic produces, the surge in demand for non processed food), I am convinced that this technology would be massively criticized and that people would be very reluctant to use it. I believe that this is the type of technology that needs a couple of generations before being adopted!

Very interesting read! I am in complete agreement with you that Modern Meadow should start partnering with luxury designers as soon as possible to retain their competitive advantage and scale their operations as efficiently as possible. By trying to produce a finished good themselves, they would then have to organize their own go to market strategies and ultimately compete with an array of luxury designers who end up utilizing the technology via other start-ups. Additionally, I believe that price will play a huge role here. There are many contemporary brands that are using faux-leather (animal free and made of polyester), who have been able to provide the same aesthetic allure that real leather provides, while also demonstrating the importance of ethical production practices to their millennial base. These faux-leather pieces are typically offered at a fraction of the price as compared to real leather goods produced by designer brands. Modern Meadow needs to ensure that the quality and price of their biofabricated goods ultimately meets the demand requirements of the end consumer in order to justify the purchase.

Super cool topic!

I’m having trouble visualizing what ‘inputs’ you feed the 3D printer to engineer tissues and organs like you mention. It’s so beyond the scope of my understanding and imagination, which is what made this article topic so intriguing!

I’ll comment on your second question: I think it would take a HUGE shift in mindset for consumers to become open to eating biofabricated foods. It sounds like the major benefit to eating biofabricated foods is environmentally motivated (i.e., saving the planet). Without a differentiable taste or cost (in fact, I would imagine it would be less tasty and more expensive relative to farmed food, at least at first), consumers will be hesitant to buy and try. Additionally, consumers already have a way to consume ethically (both in terms of being environmentally responsible and avoiding animal abuse) by consuming foods that are organically grown and free-range, as well as being a vegetarian. Current trends in the food industry like “farm to table” and “made from scratch” are here to stay at least for a while longer, so I would guess that consumers will view biofabricated foods as “fake” and “unhealthy.”

That being said, there IS a population out there who will be early adopters. I point to Soylent, the meal replacer, as an encouraging signal that people may be willing to try out novel “foods” that bring you adequate nutritional value even though seemingly strange at first. [1]

[1] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/12/the-end-of-food

Best case scenario (which has yet to be seen) the biofabricated meat should look/taste/smell exactly like normal meat, but be materially cheaper to produce and have a much lower environmental impact. The reality so far is that it has looked/tasted worse than normal meat (largely textural issues) and no major player has achieved sufficient scale to get the cost structure down. It’s still very early days, so hopefully this improves over time.

Where I could see eventually this getting really interesting, particularly for niche restaurants, is when you try to improve meat instead of simply replicating it. If you have creative control over the taste/texture/smell, you can combine characteristics in whatever way you wish (with a much shorter lead time than selective breeding or conventional manipulation methods), and that could give chefs more freedom than ever before.