Lotte at the Whim and Mercy of Chinese Nationalism

Is Lotte, Korea’s 5th largest conglomerate, at the whim and mercy of China’s rising nationalism? What can a private sector company do when an adversarial political conflict arises?

Trump is not alone trying to “make the country great again”; nationalism is spreading fast around the globe. In particular, Chinese nationalism has become more fierce and vengeful.[1] Should the trend alarm any player in the private sector?

Lotte Group, South Korea’s 5th largest conglomerate (Chaebol) with major business lines in shopping, food products, and construction, has every reason to worry. China represents Lotte’s biggest overseas market and generated more than $2.7 billion revenue for Lotte in 2015. Chinese accounted for nearly half of the million customers that poured into its hypermarkets around Asia every day. Lotte also operates Korea’s largest duty-free shop in the Incheon International Airport, where Chinese tourists alone generated 70% of its revenues.[2]

Lotte is now in a big trouble. In March 2017, China launched retaliatory actions against Korea and its businesses over its decision to deploy a U.S anti-missile system (THAAD) in Korea. The system could pose security threat to China, sparking angry nationalism among the Chinese public and policymakers. First, China banned tour groups from going to South Korea. The number of Chinese tourists halved in 2017, which hit Lotte hard. It is reported that the duty-free shop now cannot pay rent for the remaining period of a five-year contract with the Incheon Airport.[3] In addition, Beijing shut down 74 of 99 Lotte stores in China after conducting sudden fire safety inspections. Lotte closed 13 stores due to a boycott by Chinese consumers.[4]

(Picture: Empty Lotte store in China)

How is Lotte Responding?

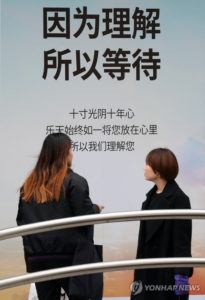

Lotte initially stayed passive with the hope that the relations between the two countries would improve soon. A Lotte official noted “The THAAD issue is not something one company can solve.”[5] However, as the conflict remained unresolved, the company implemented a number of short-term strategies. First, it launched marketing campaigns to win back Chinese customers. Chinese signs, reading “We understand you. So we wait,” were put up in Lotte’s stores to target Chinese customers. The group chairman Shin also said he loves China during an interview with the Wall Street Journal. [6]However, none of the campaigns were impactful.

(Picture: Lotte’s marketing campaign “We understand you. So we wait”)

Lotte then started pouring capital to sustain its Chinese operations. It borrowed US$300 million earlier this year to support its stores in China. Then it poured another US$300 million into its Chinese operations in August.[7] However, with the Chinese retaliatory crisis lasting longer than expected, it became difficult to sustain the business anymore. Finally, Lotte announced in September its plan to retreat from China. The company selected Goldman Sachs to manage the sale of its hypermarkets and supermarkets.

As a medium-term solution to mitigate its heavy reliance on China, Lotte has been expanding into other emerging markets, including Russia, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Its operations in those countries are relatively small at this point, but Lotte might focus on those markets and further diversify into other countries going forward.

What other steps can Lotte take?

I believe it is an unwise decision of Lotte to pull out from China. China, which has the biggest customer population and is located close to Korea, remains to be the most attractive market. It will be thus extremely challenging for Lotte to sustain its growth without tapping into the Chinese market.

As a short-term step, I recommend that Lotte drop its current plan to dispose its stores in China and instead turn them into joint venture structure with local Chinese partners. In July 2014, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said that China wasn’t interested anymore in having foreign companies take advantage of the Chinese market; he wanted them to become partners of Chinese firms.[8] Once Chinese partners own and run a significant part of Lotte’s operations through joint venture, Lotte will be in a better position to manage Chinese regulators. As successful examples, Pharmaceutical companies GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis partnered with local Chinese companies and managed to gain access to government vaccine-procurement programs.[9]

As a medium-term step, Lotte should design and push a localization strategy. General Electric has been successfully implemented its localization strategy in China by building more than 30 production sites in China, allowing Chinese partners to access GE technology, and offering training for Chinese executives. As a result, GE was able to build strong connections with the Community Party leadership and the state-owned enterprises. [10] Likewise, Lotte can share with local partners its know-how around hypermarket operations, teach local workers new skills, and invest further in the community.

Open questions

Lotte’s suffering showed that a strong economic power can severely damage foreign companies on the back of rising nationalism. What can a company do when the political conflicts are beyond its control? What is the best way to mitigate the unpredictable political risk? Do China’s retaliatory actions represent the bigger trend of rising nationalism or are they merely a one-off incident?

(798 words without picture titles)

Endnotes

[1] The New Nationalism, The Economist, Nov 19, 2016.

[2] http://news.jtbc.joins.com/article/article.aspx?news_id=NB11430906

[3] http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170904000218

[8] Globalization in Retreat (GE, the Ultimate Global Player, is Turning Local), WSJ.

[9] Past lessons for China’s New Joint Ventures, McKinsey & Company, December 2010.

[10] Globalization in Retreat (GE, the Ultimate Global Player, is Turning Local), WSJ.

The author captured an interesting recent incident in the Chinese market. The last two questions are worth reflecting for all companies reliant on the market, especially in consumer goods. However, Lotte’s unfortunate fate is not new. Japanese companies have also suffered before in multiple periods in the past decade because of political tension. 7-11 is a very similar example – some stores closed while others took any Japanese branded items off the shelf, leaving more than half the store empty. To comment on the author’s last question – is it rising nationalism? I think not. The act of boycotting a foreign brand is not a new phenomenon in China. With endless choices in the market, Chinese consumers can easily find alternatives when they wish to. Is it an one-time incident? Again, I think not. Chinese consumers are likely to continue voting with their feet in times of diplomatic friction. That said, I sympathize with Lotte because indeed THAAD is not an issue one company can solve. However, too many companies think they can gain more return in the good times and not lose more in the bad times. Too many times we see on the papers that when the Chinese market doesn’t perform as expected, companies blame the market, and not reflect on themselves. To relate to what we have discussed in FIN, China is a investment with a large beta. Companies should realize it’s high return AND high risk. To order to mitigate idiosyncratic risks, it is important to create a balanced portfolio, much like what Lotte is doing by investing in other smaller markets.

From reading this article, it seems that Lotte primarily used China as a market/distribution channel for their products. However, I’m curious if they relied on Chinese labor for manufacturing, and whether that would have made a difference with regard to the boycott against Lotte goods and hypermarkets. As we saw in the Fuyao Glass case, one of the key strategies against isolationism was to have a foot in the door of the US, so to speak. Would the “We understand you” PR campaigns have been more effective if Lotte had shown an actual investment in China vs. seeing it only as a large market to sell to?

Good question, Cindy! Lotte is known to be employing over 20,000 local employees in China, which I did not mention in my essay. However, it did not stop the government from closing the hypermarkets. Yet I agree with your thinking that the more Lotte is integrated into China’s local economy and supply chain, the more likely that Lotte would survive the government conflicts.

And this is the source: http://www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/2076419/chinese-boycott-over-anti-missile-system-triggers-us33b-sell

This is a real pickle for Lotte. Recent Chinese nationalism seems to stem from a different source than the current nationalism sweeping the West. Chinese nationalism appears to stem from a desire to create an economic powerhouse, as opposed to an appeal to identity politics to amass political power. The CPC is already powerful. They do not need to stoke identify politics, at least not as long as the economy booms.

Foreign companies are tolerated in China for as long as they add value and generate learnings for the Chinese economy. GE is still welcome because China has not yet mastered or surpassed the Western world in healthcare, wind energy, or airplane engine technology. Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (“COMAC”) is trying to supplant GE rapidly, but replacing 100 years of engineering expertise will likely take time. Google was welcome in China, until Baidu was perfected. Facebook was never welcome in a world in which Weibo and WeChat already offer superior products.

I disagree that Lotte should stick around. China is in this game for the long-run, and CPC leaders no longer see a need for foreign companies to control food distribution – the industry is simply too easy to master. Food distribution can be managed by domestic firms. GE, Ford, and Burberry are likely okay until the Chinese economy has produced equivalents.

Interesting article. It was quite naive of Lotte to think that passive messaging/marketing towards Chinese consumers would change their mind and win them over. Moreover, I believe CindyHuang’s suggestion above that Lotte should have shown investment in China as well is something they have already done – Lotte has invested $5 billion in China and employs 25,000 people (1). In the grand scheme of the $11.2 trillion (2) Chinese economy, however, this is peanuts. The JV structure proposed by the author is an intriguing solution. Though in my experience, while JVs often make sense on paper, they can be difficult to structure and execute as there can be power struggles between the two entities – and who would have controlling ownership, Lotte or the Chinese counterpart? JVs are quite useful when a company is looking to expand geographically but has little local knowledge or does not have the capital to make a full investment, both of which are not the case for Lotte. I would think the new Moon Jae-In administration, who seems to have chaebol-friendly policies, should show a unified front along with conglomerates like Lotte towards the Chinese. Maybe South Korea can afford to alienate China at the Lotte level, but it certainly cannot alienate their powerful neighbor at the geopolitical level. The implications of this Chinese boycott are of grave concern if this sentiment is to spread beyond Lotte.

Lotte is well-positioned to benefit from geographic diversification because of its wide range of businesses – from hotels to candy to petrochemicals. Its recent announcement of a partnership with Peugeot to invest $6 billion in India. Lotte plans “to invest in retail, chemicals, food processing and real estate, as well as develop railway platforms in the country” (3). Lastly, I do believe this boycott is part of a rising economic nationalism movement, on the back of slowed economic growth in China. We’ve seen local players benefit from protectionist policies and eclipse their US or international competitors: Baidu for Google, RenRen for Facebook, Weibo for Twitter, Alibaba for Amazon, and Didi for Uber (4). But one must ask if this economic nationalism ultimately hurts the local Chinese consumer who has less choices at potentially higher prices.

(1) http://money.cnn.com/2017/04/03/news/economy/lotte-south-korea-china-thaad-shin-dong-bin/index.html

(2) https://data.worldbank.org/country/china

(3) https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-23/india-is-said-to-discuss-6-billion-lotte-peugeot-investments

(4) http://www.huffingtonpost.in/rakesh-choudhary/ubers-exit-from-china-is-a-lesson-in-economic-nationalism-for-i_a_21469463/

Thank you Bismah for your insightful comments! I mostly agree with your points.

Lotte has indeed a wide range of businesses as one of the largest conglomerates in Korea. I would caveat, however, that many of its other businesses are targeting China as well. Their construction business, for example, is significant in China where the government’s permit is critical. This latest article says that Lotte fortunately received the approval to establish a huge property in China, which is a hopeful sign, but Lotte’s another property project in Shenyang is still suspended. [1] In terms of geographic diversification, I think Lotte is right about expanding into India as you mentioned. However, there are no other alternative markets that can match China’s market size. Its home market in Korea is not the answer either, with its no meaningful growth. Finally, when we look at the broader picture, there are many other Korean companies that are at even higher risk. Lotte survived the crisis, but 90 percent of Korea’s 160 tour agencies specializing in inbound Chinese tourism have closed due to China’s action.[2] So, the question is still there whether these companies are at the mercy of Beijing and what should they do about it?

[1] http://menafn.com/1096044063/China-approves-Lotte-property-project

[2] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/09/14/asia-pacific/one-year-chinas-thaad-warning-south-korean-business-suffer/#.WiIYekqnHIU

Very interesting article. Lotte truly is at the mercy of the Chinese government. As many of the other commenters have mentioned, there seems to be a significant history of China behaving in a nationalistic manner to favor domestic companies. I think Josh’s thoughts on partnering with local Chinese to gain a stronger foothold and better favor with the government definitely have some merit; however, I would worry that some of the same political risks exist even through partnering. While we’ve seen examples of companies partnering in the past, I would question whether they faced the same magnitude of political retaliation that Korea is facing and whether they will be able to overcome this retaliation simply through partnerships. The Lotte brand is still a Korean brand. I would actually side more with Lotte’s decision to pursue other markets. While those markets may be smaller and present less opportunity for growth, the company likely cannot afford to continue pushing into China with the level of resistance that they are currently facing.

Thank you Toffel for your comments! I did some more research, and it indeed looks like Korean companies that partnered with Chinese companies still suffered. The automaker Hyundai has a joint venture with a local partner in China, but it didn’t stop the Chinese consumers’ boycott when the political crisis happened, leading to 64% decrease in sales.

http://money.cnn.com/2017/08/30/news/economy/china-hyundai-south-korea-thaad/index.html

V. interesting article. In my view, Lotte’s long-term position likely requires that it mends its relationship with the Chinese consumer and enters that market. However, that doesn’t mean it needs to achieve that today and it probably makes most sense for Lotte to continue to grow through other markets and bid its time for a new entry into Chinese market (e.g., future acquisition).

One way to look at my strategy is by taking a line from the famous Chinese strategist, Sun Tzu in ‘The art of war’,: “If your enemy is secure at all points, be prepared for him. If he is in superior strength, evade him. […] Pretend to be weak, that he may grow arrogant. […] Attack him where he is unprepared, appear where you are not expected.”

Very interesting to see how Chinese Nationalism impacts non-Chinese businesses that heavily rely on the Chinese markets for revenue.

In the case of Lotte, I found it’s strategy to simply “wait it out” very misinformed–in times of nationalism there is a pride and emotion that builds up in the country. If the foreign company’s reaction is to simply dismiss it and “wait it out”, I can imagine that the Chinese population would find that a bit condescending and further foster it’s commitment to Chinese-based companies. It almost signals to the Chinese population that Lotte thinks their nationalistic pride is simply a fad, ungrounded in actual logic, and something that will pass quickly. Their ad campaign of “So we wait” may very likely have made things worse.

I very much liked the author’s suggestion to change the perception of Lotte as a foreign company to one that is Chinese-based. The idea of a Joint Venture, even if only for the hypermarket business line, would respect its consumers’ choice to support Chinese-founded retailers while changing the perception that Lotte is “foreign”. This is a great way to role model its commitment to the Chinese economy to gain the trust of its Chinese consumers. Another thought is to heavily recruit for Chinese students and talent to work for Lotte, either through heavy subsidization of living in South Korea to work at HQ, or a large amount of job availability to run its Chinese operations. Given that the Chinese market makes up such a large part of its revenue, it would be a worthwhile investment for Lotte.

Like MS, I agree with with the author’s suggestion to form a deeper partnership with China through investment and true partnership, beyond their ill conceived ad campaigns (did they really think that would work? Reminds me of Kerr McGee’s ads…) I understand Bismah’s point on JVs being difficult to execute and structure, and power dynamics would certainly be at play here, but it’s unclear what other options they have. Given that China is Lotte’s biggest overseas market at nearly $3B in revenue it’s difficult to imagine a scenario where new markets can even come close to scaling quickly enough to compensate for this revenue shortfall, let alone continue to drive growth.

As we have talked in class, political risk tends to be a strong systematic risk that is hard to differentiate away, or even predict. With the current political environment in East Asia already tensed up by North Korea’s aggressive military actions, Lotte should try to diversify its investments and reach new contracts to support their business in China. As you mentioned in this case, the Chinese consumers tend to be the biggest market for Lotte, so it would be risky to leave the current market in order to seek even riskier markets like Thailand and Russia. I highly agree with you assessment of the short-term and medium-trend strategies, and I would add a long-term strategy to support your arguments. When Walmart attempted to move into Japan in the early 1980s, they were initially unable to transplant their operations to the island. Moreover, it was really hard for the company to understand the retail dynamics of a Japanese consumer, and their original plan to run Walmart-owned stores in the island had to be changed. As a result of a new long-term strategy, Walmart chose to enter a JV contract agreement with Japanese retailers and investors to deploy a reduced asset strategy. Thanks to this switch in strategy, Walmart has been able to influence Japanese retail via the Seiyu partnership, while also obtaining the support of Japanese consumers and investors.

*Walmart made an initial investment of about 7-8% of Seiyu’s shares in 2002, and ultimately acquired the remaining shares of Seiyu to turn it into a subsidiary of the Walmart group.

It seems strange to spend so much money to try and wait the government out and try and “win customers back”. How much of the decline was driven by something that was under the customers’ control vs. policies implemented by the Chinese government? I’m not sure that there was much that the customers could have done differently even if they wanted to.

I like your recommendation of entering into JVs with local partners to try and appease the government / customers. One question that I have about how these typically work in China, is regarding who has operational control? Would Lotte be able to continue managing the Chinese operations, or would they need to take a passenger seat role to a local partner?

This is a very real and increasingly salient issue that every global company needs to start thinking about. Lotte’s example makes it clear that the Chinese government believes that they can punish foreign companies (i.e., Lotte) in order to force their government (Korea) to cooperate with China in the geopolitical arena, given the sheer size and deep pockets of the Chinese consumer economy. I think this strategy has been successful in the past and will likely continue to be successful while the Chinese economy continues to grow, but if the Chinese economy hits a snag and spending power sees a meaningful decline, this approach will not be as effective because foreign companies will have less to lose (although realistically, given the population of China, I don’t envision a world in the foreseeable future in which companies would be willing to forgo the Chinese consumer). I think as nationalism continues to rise around the world, the lesson for companies is to diversify their business so that they are not disproportionately dependent on a single country (outside of their home) for their survival.

As stated by a number of previous comments I believe that it will be difficult to persuade China to loosen up its agenda on pushing protectionism to better their own businesses at this point in time. It seems clear that for industries that they have relative mastery over that they will favor their own businesses. I think it may make more sense to adapt some sort of Alibaba-like strategy where you create various holding companies and structure ownership so that the company at least “appears” to be a Chinese company. This may require some transactions first as I’m sure the name recognition would pose a problem.

o This article shows one of the biggest trade-offs of entering the Chinese market – the ability to reach one of the largest consumer bases, but in a country where the government has significant power to affect industry. Lotte is in a particularly bad position as they do not have as much retaliatory power as a larger, multinational company or a company in a larger global economy would have to prevent China from taking these measures. In that way, one alternative solution could be trying to get the involvement of the South Korean and/or US governments in combatting these measures. Lotte may not have the size or lobbying expertise to do this effectively, but China’s reactions to the South Korean military exercise could have a significant impact on the broader South Korean economy, not just Lotte. Because of the economic impact, South Korea could begin to rethink specific military moves. This likely causes concerns with the US government as South Korea serves a strategic role in the US military’s operations. With that, the US government should be incented to support companies, like Lotte, that are facing retaliatory measures from the Chinese government. These actions are likely more long-term though and in the meantime, Lotte should to embed itself more in the Chinese economy as the author described.

I’d like to address two questions raised by the author:

What can a company do when the political conflicts are beyond its control?

–I’m susceptible to the strategy of focusing on other markets as mentioned in the post (e.g. Russia, Vietnam, and Indonesia). I think Lotte risks falling victim to the sunk cost fallacy, having already invested $600MM in Chinese operations with really nothing to show for it. I realize the Chinese market potential is massive, but the political/trade risks strike me as too volatile and unpredictable to successfully operate there. One means of re-entering the Chinese market could be a long-term play wherein Lotte continues to build its brand in neighboring countries to the point where Chinese consumers are willing to travel abroad to purchase its products. I think that if the Chinese government realized this trend it might sway back toward inviting Lotte to operate in China so as to capture revenues currently being diverted to other economies.

What is the best way to mitigate the unpredictable political risk?

–Lotte could also perhaps avoid political risk by going one step further from partnering with local firms to actually establishing an independent entity wholly-owned by Chinese investors and heavily reliant on new manufacturing operations in China employing local workers. This could assuage Chinese regulators’ fears that Lotte is merely taking advantage of the Chinese market. One downside, of course, is that this approach minimizes Lotte’s brand control in China and could subject it to eroded perceptions of the company should Chinese managers stray significantly from the model that accounted for its initial success in Korea.

This article was very interesting. I was unsurprised to read that China has basically forced Lotte out, as there is a history of China supporting domestic companies. While I support keeping Lotte in China, I would only do so dependent on what expectations Lotte management has. If Lotte expects that they will manage the company or make major decisions, they should pull out, as I doubt the Chinese government or businesses would allow that. However, if Lotte is looking to make some money by investing or utilizing its supply chain, staying in China may be a possibility — Lotte just has to be comfortable with ceding the majority if not all decision making power.

In response to the questions posed, companies can mitigate political risk by diversifying its operations into different locations. By doing so, the company has minimized idiosyncratic risk of that specific location. Additionally, I do not think China’s actions is a representation of nationalism — it’s simply a way for one nation to pressure another into conforming to its demands. In this case, China was reacting to an event, rather than organically feeling nationalistic and kicking Lotte out of the country. These actions will most likely become more commonplace as China feels it has increased power to influence and make demands in the world.

One company cannot change defense policy for a world superpower just as a few ads cannot change the minds of a nationalistic government. Lotte should focus on expanding its footprint to more companies in an effort to diversify political risk – Russia perhaps is not the best choice considering it is friendly to China and considered hostile towards the US – with China already against them, it would seem they run the same risk trying to expand into a similar environment in Russia. Their focus instead could be on more developed markets in Asia – India, Japan, etc that hold a range of political views and lean towards somewhat less nationalistic tendencies.

I do not believe that China’s retaliatory actions represent a negative trend of rising nationalism. China’s requirements for foreign firms to partner with local partners provide an interesting degree of alignment of interests / win-win situation for both international entities and the local market/population.

After a semester of class discussions, I feel it is important to surface that global (and/or US) firms, particularly retail/consumer brands, expanding to new emerging markets can have a quite colonialist effect/be based on an imperialist mindset, in which firms “create a lot of value” for themselves and less attractive (or too diluted) benefits for the local market (e.g. mostly low-skilled job positions). Speaking from an emerging markets, protectionism presents this fine balance between encouraging local companies to develop/innovate and feeding complacency. To achieve new levels of competitiveness, such markets should do a better job in trading access to its growing economy/population/market with more strategic and long-term benefits.

In this scenario, international companies would benefit from access to an attractive market while locals access new technology, develop business practices and strengthen its economy as a whole.

Given that Korea and China have a history of tense political negotiations, I agree with the author that Lotte should investigate opportunities to partner with local Chinese firms for their stores located in China. Just recently in the news, and perhaps as a gesture to thaw relations, China has relaxed a bit on its restrictions of tour groups traveling to South Korea [1]. However, I think that the Chinese government has clearly showed its hand to Lotte: When Korea doesn’t behave the way the Chinese government wants, then Korean businesses will suffer the consequences. I wonder if there’s something that Lotte could do to demonstrate that when their stores suffer (or are not allowed to operate), then the Chinese customer and employee base suffers. It would be beneficial for Lotte to diversify their customer base and store locations so as not to be as reliant on the Chinese consumer, given that access to the Chinese market is not guaranteed.

[1] CNBC, “China partly lifts ban on group tours to South Korea, online curbs stay”, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/28/china-partly-lifts-ban-on-group-tours-to-south-korea-online-curbs-stay.html, accessed November 2017.

Interesting article. I agree with your suggestion to play by the Chinese government’s book and establish some sort of JV. Losing the Chinese market entirely will be a major blow to Lotte’s financials. I’m worried about the second order effects to Lotte- to what extent were Lotte’s operations, supply chains, and internal org structures, designed to accommodate their Chinese business? How will that all have to shift now?