Is flood relief pouring into all the wrong places?

Thanks to climate change, the timing and location of natural disasters are as unpredictable as ever. How, then, can humanitarian aid stay ahead of the storm?

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is in the business of disasters. Needless to say, they have been very busy lately. Thanks to climate change, our new reality is that natural disasters are becoming less the exception and more the norm [1]. With such a scary prognosis, one might assume that a company in the disaster business is ripe for expansion – natural disasters have cost the world $1.3 trillion in damages and 1.1 million lives in the past 12 years [2].

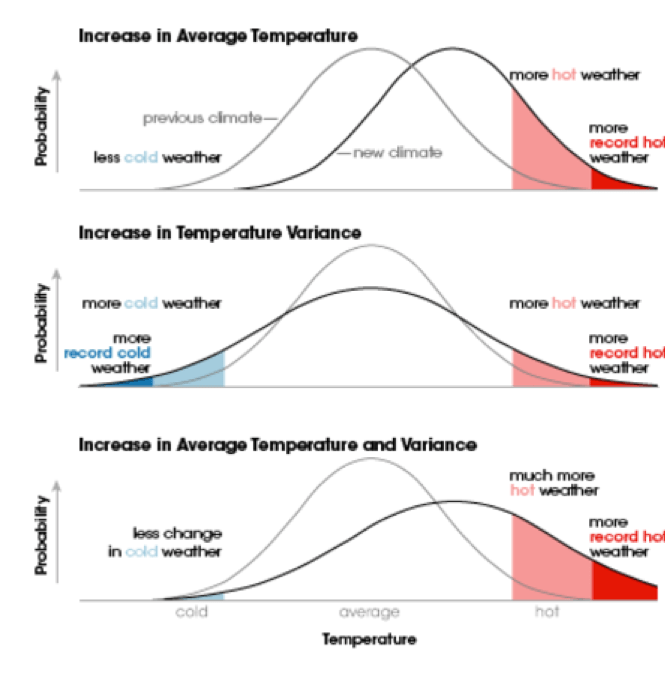

In reality, however, climate change has thrown a wrench into the operational model of IFRC. The culprit is not the increasing frequency of disasters per se (though frequency has strained capacity to some extent). Rather, it is the unpredictability of such disasters. Put differently, if all that climate change affected was the average temperature, forecasting would remain predictable, and resources would arrive to the correct places at the correct times. But climate change also increases the range, or variance, of temperatures experienced. Variance is the catalyst of unpredictability, which can make it nearly impossible for humanitarian organizations stay on the front-end of disaster (Exhibit 1) [3]. Exhibit 1: Climate change increases both average temperature and temperature variance. Temperature variance leads to less predictability in climate forecasting, which in turn makes it difficult for humanitarian organizations to “beat the storm.” (SOURCE: NASA Earth Observatory)

Exhibit 1: Climate change increases both average temperature and temperature variance. Temperature variance leads to less predictability in climate forecasting, which in turn makes it difficult for humanitarian organizations to “beat the storm.” (SOURCE: NASA Earth Observatory)

The IFRC Approach to Disaster Management – Potential Pitfalls

Aid relief at IFRC operates under a series of relatively linear processes. As shown in Exhibit 2, the first step in disaster management is to identify areas with the most need. Of all the steps, this first one is the most vulnerable to unpredictable weather patterns – without the ability to predict where a storm or earthquake will hit, risk reduction efforts can be misdirected, leading to even higher demand downstream [4,5].

Exhibit 2: Disaster relief process map. Poor execution of Risk Reduction Step 1 can lead to worsening damage downstream. This in leads to higher costs for IFRC, as recovery is more expensive than risk reduction.

What are they doing now?

The IFRC is aware that to operate as efficiently as possible, they need to optimize Risk Reduction Step 1 – resources need to be at the right place at the right time, before disaster strikes. Consequently, in the past six years, they have “more than tripled their preparedness” efforts – doubling down on their presence in existing communities, and in new, untapped areas, are “strategically pre-positioning relief items for rapid deployment” [5].

However, quick deployment is useless without good measurement. In climate science, such forecasting is by no means a new concept. However, in recent years, IFRC has partnered with the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) at Columbia University to develop a more accurate, cutting-edge tool used for long-term global forecasting (Exhibit 3). Soon after launch, the tool was put to the test in West Africa, successfully detecting a large, potentially detrimental storm before it struck. This in turn led to more effective ‘pre-disaster’ risk reduction, which generated cost savings of $18 per beneficiary [6].

Exhibit 3: New partnerships with academia have created better, more customizable forecasting for IFRC. (SOURCE: IFRC Climate Centre)

What should they do next?

While good measurement is a step in the right direction, IFRC should adopt three additional measures to ensure that its process map (Exhibit 2) aligns with the growing unpredictability of our climate.

1) Establish global partnerships with climate scientists to aid in forecast interpretation and information dissemination: Decision-making chains are not always fully prepared to process the information that is being forecasted. In other words, even if a storm is detected on time, it is difficult to translate information from Columbia to aid supplies in West Africa. Decentralizing the forecasting process to other nations and other scientists can alleviate that delay.

2) Begin “pre-disaster preparation” even earlier than originally anticipated. This will prevent a dangerous “backlog” in the event that a disaster arrives sooner than planned.

3) Adopt more aggressive internal fundraising. 80% of IFRC’s operating income comes from voluntary contributions, which usually spike in the days-weeks following a disaster [8]. Unfortunately, these spikes in revenue are not in line with the time in which IFRC needs to increase its resource utilization, namely, in the weeks-months before a disaster.

In conclusion, our increasingly unpredictable climate has created an increasingly unpredictable supply chain for IFRC. Can further dissemination of forecasting technology beat storms to the punch, or are humanitarians simply fighting an uphill battle?

(784 words)

Sources

[1] IPCC, “Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report, https://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/spms1.html

[2] UNISDR “Global Assessment Report 2015,” https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/gar

[3] NASA Earth Observatory, “The Impact of Climate Change on Natural Disasters,” http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/RisingCost/rising_cost5.php. Accessed November 2016.

[4] IFRC, “Preparedness for Climate Change,” http://www.ifrc.org/Global/preparedness_climate_change.pdf. Accessed November 2016

[5] Jennifer Leaning, M.D., Debarati Guha-Sapid, Ph.D, “Natural Disasters, Armed Conflict, and Public Health,” New England Journal of Medicine, no 19 (2013):369, via PubMed, accessed Nov 2 2016

[6] Lisette Martine Braman, “Climate forecasts in disaster management: Red Cross flood operations in West Africa, 2008,” Disasters, no 1 (2013):37, via PubMed, accessed Nov 2 2016

[7] IFRC Climate Centre, “IFRC/IRI Map Room,” http://www.climatecentre.org/climate-info-and-forecasts/ifrc-iri-map-room. Accessed November 2016.

[8] IFRC Independent Auditors’ Report on Consolidated Financial Statements, 2015, http://www.ifrc.org/Global/Publications/Finance/IFRC-Consolidated-financial-statements_2015.pdf. Accessed November 2016

Very interesting! I expected the Red Cross to struggle more with the increased frequency of disasters rather than the unpredictability since there has always been a degree of uncertainty with natural disasters. There have also been encouraging research and technological advances in predicting natural disasters. For example, in CA they have starting using an early warning system to notify people before an earthquake hits (http://www.cisn.org/eew/). While it currently only gives advance notice of tens of seconds, it’s an encouraging start. As the IFRC struggles to anticipate what new areas are at risk given climate change, it would be helpful for them to do regular assessments based on clear evaluation criteria. For example, what temperatures are associated with higher than average rates of infectious diseases, what levels of environmental degradation identify an at-risk location? Quantifying these metrics can improve the accuracy of the first step in disaster management and lead to improved response in risk reduction as well as recovery.

A pertinent issue. I wonder if the IFRC can be trusted to be the best organization for leading this change. While they are involved in important missions, various components of IFRC seem variable on abilities to respond in the near and long terms to floods. I have hope in your suggestion for partnering with climate scientists and having better assessment capability, but I’m not as confident in their on-the-ground ability to use these insights.