Insuring Against Climate Change

It is more imperative than ever for insurance companies to both underwrite the impact of climate change on future claims as well as consider innovative solutions that can capitalize on these new potential opportunities.

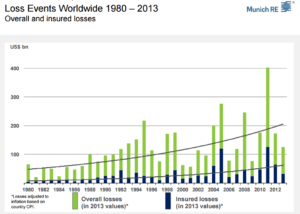

In 2011, the insurance industry suffered record-setting losses of $105 billion in natural disaster-related claims. This was driven primarily by a mix of earthquakes in Japan and New Zealand, flooding in Thailand and Australia, as well as tropical storms and tornadoes in the U.S. While this may seem like a one-off incident, aggregate weather-related losses (i.e. including uninsured losses) around the world have risen from an annual average of $50 billion in the 1980s to over $200 billion over the past 10 years.

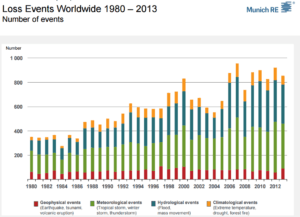

Moreover, the number of events has increased from less than 400 a year in the 1980s to an average of nearly 800 a year, as shown in the exhibit below.

A significant portion of these losses are driven by climate change-related activities, particularly hydrological and meteorological events. Given impact of climate change on the pattern of future natural disasters, it is more imperative than ever for insurance companies to both underwrite the impact of climate change on future claims as well as consider innovative solutions that can capitalize on these new potential opportunities.

Climate Change Modeling

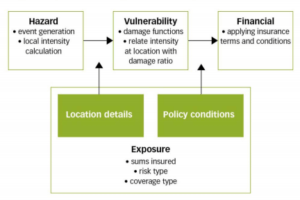

Lloyd’s, an insurance market established in 1688 when merchants first bought insurance for their cargo ships, is one of the oldest insurance organization in existence today. However, it wasn’t until the 2014 US National Climate Assessment report came out that Lloyd’s for the first time called on its constituencies to incorporate climate change into their catastrophe models. Catastrophe modeling, or “cat models,” is a relatively young field that combines actuarial science with the geological study of natural hazards. Commercially available models were not available until 25 years ago, and the early models were of such low sophistication that the 1992 Hurricane Andrew resulted in the immediate insolvency of 11 insurers in the United States. A catastrophe model essentially uses certain vendor-specific data and assumptions relating to vulnerability and hazard risk of natural disasters, and takes as inputs the insurer’s financial exposure and coverage location to determine the potential risk of the book (see exhibit below).

However, while older catastrophe models were backwards looking and relied heavily on historical data to extrapolate probabilities, researchers have begun to investigate how to incorporate forward-looking climate change data in evaluating the potential size of losses. For example, a study by Paul Wilson, senior director of model development at Risk Management Solutions (RMS) showed that the impact of sea level changes over the past 50 years drove a 30% increase in New York City’s losses from Superstorm Sandy in 2012, something that would not have been factored into older catastrophe models. Another equally compelling paper by James Elsner from Climatek suggests and estimated 5% per year increase in losses due to changes in sea-surface temperatures, which is a key driver of hurricane activity in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Lastly, a study by Professor Lamb, Chief Scientist of JBA Group showed that there was at least a 20% increase in the likelihood of floods in the UK at the same magnitude of as the winter 2000 flood, with all the increase being attributable to human-induced climate change. Ultimately, given the duration of many catastrophe insurance contracts (many of which are multi-decade), it is essential that insurers like Lloyd’s are able to better understand and forecast how changes in global climate will impact future risks.

New Opportunities?

On a more positive note, climate change also presents significant business opportunities for insurance companies. For example, given the billions spent and expected to be spent on clean energy technologies, this will be a significant new capital base requiring various insurance functions. Some large insurance companies have already begun to build out divisions dedicated to servicing these functions, such as AIG’s Global Alternative Energy Practice. This is an area that Lloyd’s constituencies are still currently lacking in, as most continue to focus on more traditional property and casualty and reinsurance businesses. Other innovative insurance products that Lloyd’s and other insurers should look into relating to energy and climate change include “green building” insurance, or insurance for renewable energy and energy efficient projects. Another area of opportunity would be micro-insurance, where companies can offer weather-related insurance to small individual farmers in the developing world who currently lack access to traditional hedges and insurance options but are heavily affected by climate change.

Looking Forward

Ultimately, insurers such as Lloyd’s should take a two-pronged approach when it comes to thinking about climate change—build greater sophistication into their models to incorporate higher potential future losses, and think about new insurance opportunities generated by climate change and the push towards clean energy.

(759 words)

__________________________

Sources:

http://evanmills.lbl.gov/pubs/pdf/climate-action-insurance.pdf

https://www.lloyds.com/~/media/lloyds/reports/emerging%20risk%20reports/cc%20and%20modelling%20template%20v6.pdf

https://www.lloyds.com/news-and-insight/news-and-features/environment/environment-2014/making-renewables-bankable

https://www.munichre.com/us/property-casualty/press-news/press-releases/2015/150107-natcatstats2014/index.html

https://www.munichre.com/site/wrap/get/documents_E-1959049670/mram/assetpool.munichreamerica.wrap/PDF/2014/MunichRe_III_NatCatWebinar_01072015w.pdf

http://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/business-action/sustainable-finance/climatewise

http://www.swissre.com/media/news_releases/nr_20111215_preliminary_estimates_2011.html

http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/76/76115/aig_climate_change_updated.pdf

Frank, thanks for this insightful look at catastrophe modeling in the insurance industry. I agree that the insurance industry has an important role to play in helping the world prepare for and adapt to some of the effects of climate change that are already inevitable. Governments around the world are agreeing with this perspective. Just last year, during the Paris climate talks, President Obama announced a $30 million contribution to help small island nations access”climate risk insurance” (for more info, see: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2015/12/250173.htm). And the Group of 7 (G-7) nations have set a goal of expanding “climate risk insurance” to 400 million people by 2020. In addition to the modeling-related issues you raise in the post, I would also emphasize the importance of rapid payouts, so that individuals, companies, or governments struggling after a catastrophic event can access much-needed funding to support recovery efforts.

This was a great in-depth look at how the insurance industry would be impacted by climate change. It got me thinking about the impact of these changes on the end consumer of insurance plans. If insurers get smarter about incorporating climate change-induced catastrophes into premiums, I’d expect the premiums to increase for the end user. Would consumer behavior adjust appropriately such that overall revenues from insurance premiums go up, or would consumers skeptical of catastrophic risk balk at the increased premiums? And given that climate change experts’ forecasts differ dramatically, how would these insurers pick a view? Do we know enough to predict with more geographical accuracy, where these catastrophic events might occur to adjust premiums appropriately, or would higher climate change fees be peanut-buttered across all customers?

Frank,

Great article – I’m glad to see this issue getting some airtime. I still worry though, that insurers, even with the forward-looking climate change data and greater sophistication in models, it will still be too difficult to evaluate the potential flood losses. I think FEMA has a role to play here in helping to distribute the risk appropriately. Concentrating all the flood insurance in one central insurer, such as FEMA, should help to distribute the risk of loss across a wider pool of insured persons. Obviously this doesn’t solve the problem, and the more sophisticated models you discussed are needed her as well.

https://msc.fema.gov/portal

Very interesting that we are starting to see climate change factor into quantitative modeling for risk and insurance purposes! Many years back during my hedge fund days, I asked the energy and commodities traders whether they could see any evidence of climate change creeping into their forecasting models or in any market prices. At the time, it was a firm “No”, mostly because the impact was far too small relative to the daily volatility of the asset class. Also, most commodities futures are only liquid enough about one year to expiry. I could imagine a not-so-distant future where climate change creeps into the models; a slight but necessary and important adjustment, similar to the way we build in convexity corrections into the long end of a fixed-income yield curve.