How can Vietnam’s government integrate into global supply chains after American abandonment of the TPP?

When President Trump walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership to put America First, the biggest loser was the people of Vietnam. But the Vietnamese government has other means to integrate into global supply chains.

What was the TPP and what did Vietnam stand to gain?

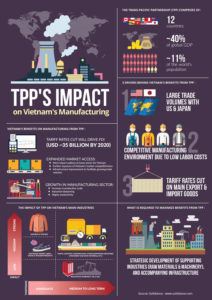

The Trans-Pacific Partnership was a trade agreement between 12 Pacific nations,1 comprising 40% of global GDP and one-third of global trade.2 Explicitly, the agreement aimed to reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade and created enforceable commitments on environmental, intellectual property and labour organisation protections for signatories. Implicitly, the TPP was a geopolitical tool in the context of the Obama Administration’s pivot to Asia to counter a growing dependence on China amongst other signatories and bring them closer to the US. Trump’s isolationist “America-first” campaign pledged to abandon the TPP to protect American workers – which he did on day one in office.3

World Bank4 and think tank5 studies predicted that Vietnam would have been the biggest relative beneficiary of the TPP in terms of:

- GDP growth attributable to the agreement – 10.1% by 2030

- Export increase attributable to the agreement – 30% by 2030

- Foreign direct investment inflows attributable to the agreement – 14.4% by 2030

Of all signatories, only Malaysia was close to this level of relative gain (5.6% of GDP) with all others predicted to benefit by 0.1-2.0% of GDP.6 GDP growth through greater integration in the global trade and supply chains would directly lift living standards of the Vietnamese people.

To explain the benefit qualitatively: Vietnam’s low cost labour and strategic location was beginning to attract transnational corporation (TNC) investment (such as Samsung7 for electronic assembly, and dozens of players in apparel). The TPP would remove tariffs (such as a US tariff on imported shoes), pushing Vietnam further down the cost curve compared to neighbours, particularly China. In the short-term, Vietnam would capitalise on its ‘population dividend’ of a large, young, low-wage population to deeply embed itself in the global supply chain as a low-cost manufacturer and in the longer-term take advantage of these investments as an opportunity to move up the global value chain, e.g. by better educating its workforce and serving TNCs with supporting industries.

(Source: Solidance’s March 2016 White Paper on the TPP’s Impact: http://www.solidiance.com/whitepaper/download/trans-pacific-partnership-a-boost-for-vietnams-manufacturing-growth.php)

What should the Vietnamese government do now?

Absent the TPP, the Vietnamese government can:

- Make medium-term investments in infrastructure and longer-term investments in education to attract TNCs

- Focus on improving the ‘quality’ of incoming foreign direct investment (FDI) over time

Before proceeding, this paper notes at 11/13/2017, TPP signatory leaders are meeting at APEC to discuss a resurrected TPP without the United States.8 President Trump also visited Vietnam prior to APEC and indicated an open-ness to bilateral trade agreements. Vietnam should vigorously pursue these deals, tempered by an awareness that a mega-trend of isolationism could torpedo them again.

- Investments

Over the medium-term, infrastructure investments will attract TNCs and increase Vietnam’s cost competitiveness, facilitating greater supply chain integration. One key area is ports: a World Bank report estimates “it costs US$610 per container to export from Vietnam in 2014 as opposed to US$460 from Singapore, US$590 in Hong Kong and US$525 in Malaysia”.9 Power investments are also critical – TNCs highlighted reliability and cost of electricity as key concerns in making investment decisions. For the large-scale low-cost manufacturing Vietnam is seeking to court the price advantages from these investments can deliver outsize returns when they are used to strategically attract the right firms.

Longer-term, Vietnam needs to invest in the quality of its workforce. Today it’s demographic dividend provides a young and large population that demands low wages compared to its key competitor, China.10 Longer-term, this advantage will vanish as the advantage goes downstream to countries like Myanmar. Vietnam needs to educate its workforce now so they can seize opportunities for higher value-add labour – particularly in engineering.

- Improving FDI quality

Vietnam should prioritise accepting and incentivising FDI that will have the greatest benefit to integrating it into the global supply chain. One way to do this is to focus on developing ‘clusters’ of related industries. This will increase the ease with which local supporting industries can serve multiple global players and allow Vietnam to have economies of scale in education and infrastructure investments. This theory was advanced by Porter as a key way for nations to secure a ‘competitive advantage’11 – and the Vietnamese government is beginning to develop an apparel industry cluster. Additionally, the government can incentivise or negotiate FDI deals that accelerate global supply chain integration – e.g. that have a mandate for technical education of a certain number of local employees.

Open questions

Vietnam has limited resources and political capital. The key questions its faces are how to best use these.

(i) Given isolationist trends, which countries or regions will be the most fruitful to pursue trade deals with?

(ii) With imperfect information how can Vietnam adjudicate which levers will have the biggest impact when comparing, say, incentives for TNCs to enter versus creating engineering colleges?

How the Vietnamese government answers these questions will determine how well Vietnam can enter the global supply chain and lift living standards for its people.

End notes

1. The twelve nations are Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States and Vietnam

2. New York Times, “What is TPP? Behind the Trade Deal that Died”, 01/23/2017, accessed at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/business/tpp-explained-what-is-trans-pacific-partnership.html on 11/11/2017

3. Ibid.

4. Global Economic Prospects (World Bank Publication), Potential Macroeconomic Implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, January 2016, accessed at http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/847071452034669879/Global-Economic-Prospects-January-2016-Implications-Trans-Pacific-Partnership-Agreement.pdf on 11/11/2017

5. Petri, P. A., Plummer M. G. The Economic Effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: New Estimates, January 2016, Peterson Institute for International Economics

6. Ibid

7. Retuers, Samsung ups Investment in Southern Vietnam Project to 2 Billion, 12/29/2015, accessed at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-samsung-vietnam/samsung-ups-investment-in-southern-vietnam-project-to-2-billion-idUSKBN0UC0XX20151229 on 11/11/2017

8. Financial Times, Pacific Rim Countries Close in on TPP Deal without US, accessed at https://www.ft.com/content/82c29b4a-c616-11e7-a1d2-6786f39ef675 on 11/11/2017

9. Vietnam Briefing, “Privatization of Vietnam’s Port Infrastructure to Boost Efficiency and Lower Prices”, 13 February, 2015, accessed at http://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/privatization-vietnams-port-infrastructure-boost-efficiency-prices.html on 11/11/2017

10. Devonshire-Ellis, C. The Cost of Business in China Compared with Vietnam, 05/26/2015, ASEAN Briefing, accessed at https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/2015/05/26/the-cost-of-business-in-vietnam-compared-with-china.html on 11/11/2017

11. Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations, 1998

The questions posed by this article are intrinsically the same for every emerging country trying to find a (economic) place in this world. Infrastructure and Education are in fact the logical levers to attack in the mid- and long-term, which could indirectly affect other conditions in the country (e.g. access to health). However, what to do now, the short-term? Some countries in LatAm and Africa have benefited from tactical ‘alliances’ with countries in their vecinity, building stonger and complementary supply chains. I’m not really sure what’s the environment in SEA, but this could be a potential idea to tackle immediately.

The article presents some very challenging trade-offs that must be faced when resources are scarce and the country is heavily dependent on the export market. Considering the already highlighted imperfect information, I believe that Vietnam should pursue trade deals with countries that are growing, that have complementary needs and that perceive the exchange between them as an opportunity for both sides. In addition to that, Vietnam will need to engage on agreements with several countries to add up similar benefits as it had under the TPP. It will definitely not be an easy task, but, in the end, the Vietnam will have a more diversified set of alliances and consequently be less susceptible to pressure from one single country. In that context, trade deals with the EU and the MERCOSUL seem to be a good option.

This article does a really good job exploring the impacts of the collapsed TPP on an micro level, looking at individual people, as opposed to the macroeconomic view that is usually taken by politicians and the media. In response to your question about how Vietnam can assess which levers it can pull to increase its attractiveness to TNCs, it’s possible that Vietnam should be looking to make social changes instead of the economic investments presented in your article. With the TPP with the US dead for now, Vietnam is looking to form an agreement with Europe, but is hitting road blocks due to questions about its human rights violations and the way it treats its people [1]. Given the limited resources that Vietnam is working with and the amount of time it would take to implement something like an overhaul of the education system, I think Vietnam should start by looking at some low-cost internal policy changes they could make in the short term to increase their attractiveness to TNCs.

[1] Jennings, Ralph. “Vietnam’s TPP Backup Plan, A Free Trade Agreement With Europe, Is Facing New Obstacles.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 03 Mar. 2017. Web. 01 Dec. 2017. .

Fantastic article that educated me on the implications of US isolationism on the smaller players in TPP.

My biggest question, and suggestion for Vietnam, is: why not China? Given the United State’s clear reticence to incentivize pacific countries to align with US interests, surely the Chinese are happy to step into the economic void. I thus suspect, given China’s ever-more-prominent role, that Vietnam could gain some significant trade concessions with China using the resurgent TPP as leverage. I do not know the tradeoffs, but there must be an opportunity to align with China at minimal domestic risk. China has certainly shown a willingness to provide high-quality FDI, and if Vietnam is willing to align itself I suspect that China would be happy to direct investment to Vietnam that it is losing to lower-cost countries anyway (eg, apparel, as the author notes, going to Myanmar).