H&M: Environmental Steward or Greenwashing Marketer?

H&M has incorporated eco-friendly practices in its operational strategy, but the fact remains that a fundamental tension exists between the enormous environmental footprint generated by its fast fashion business model and its aim to produce sustainable garments.

The meteoric rise of the global fast fashion industry has completely upended the two-season retail shopping experience, conditioning consumers to instead expect and demand the arrival of mass-produced, affordable, and on-trend pieces at increasingly shorter buying cycles. While the business model has afforded retailers with tremendous growth that outpaces that of traditional apparel players, top-line gains were realized at the expense of environmentally sound manufacturing practices. Already the second largest polluter of freshwater resources, the fashion industry is also responsible for the production of synthetic fibers that emit N2O, a gas 300 times more damaging than CO2 [1]. Fast fashion garments, in particular, “produce over 400% more carbon emissions per item per year than garments worn 50 times and kept for a full year.” [1]

Amongst its peers, H&M was one of the first to integrate large-scale sustainability initiatives across its supply chain. Sustainability has played an increasingly critical role in H&M’s operating model since 2011, when it launched its Conscious Collection, an annual collection produced with such eco-friendly materials as hemp, organic cotton, and recycled polyester [2]. To complement the main collection, an assortment of eco-friendly pieces under the Conscious brand were made available year-round. Other initiatives quickly followed. Launched in 2013, the Garment Collecting Program provides customers the option to recycle their old clothes and home textiles at an H&M store, regardless of the brand or condition [3]. In return, the customer is gifted with vouchers for use at H&M [3]. Over 12,300 tons of clothing was collected in FY2015 and H&M has, to-date, produced 1.3mm garments using recycled clothing from the program [4].

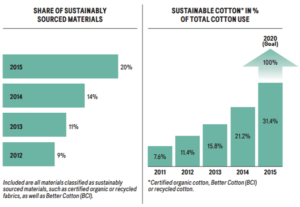

On paper, H&M appears to have made considerable strides in realizing its sustainability aims. By the end of fiscal year 2015, 78% of H&M stores operated on renewable electricity (up from 27% in FY2014), which slashed its own greenhouse gas emissions by 56% from 2014 [5]. Committed to maximizing its usage of sustainable fibers in order to transition to a 100% circular business model, H&M has shifted its reliance on organic cotton, organic wool, recycled polyester, and recycled wool [6].

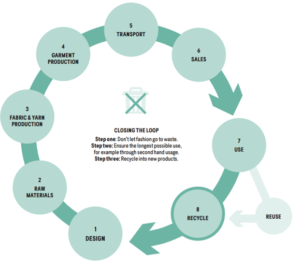

Exhibit 1. H&M, Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015

Water management has been another key area of focus for the company. Fashion is a water-intensive industry, particularly due to the amount of water necessary for cotton production and fabric dye processing [7]. To achieve its aim of global water stewardship, H&M required that its ~500 supplier factories with wet processes institute wastewater treatment measures, reduced the water used during treatment processes for its denim garments, and is on track to introduce water-efficient equipment across its value chain [8]. Already one of the world’s largest users of organic cotton, the company has set an ambitious goal of sourcing its entire cotton supply from sustainable sources by 2020 [9].

Exhibit 2. H&M, Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015

H&M has incorporated eco-friendly practices in its operational strategy, but the fact remains that a fundamental tension exists between the enormous environmental footprint generated by its fast fashion business model and its aim to produce sustainable garments. The retail giant currently operates more than 4,100 stores in 61 markets [10]. Armed with an aggressive expansion strategy, H&M plans to open an additional 425 new stores in three new markets in fiscal year 2016, as well as introduce one or two new brands in 2017 [10]. Incentivizing shoppers to trade in their old clothes for a store coupon helps to reduce textile waste on one hand, but it’s also a clever marketing scheme that brings the consumer back into the store to make additional purchases, which ultimately broadens the company’s environmental footprint. Moreover, several of H&M’s key production markets in emerging economics have regulations in place that prevent the importation of used clothes and recycled materials currently comprise of only 1% of H&M’s total material use [6]. Separately, current technological limitations permit only 20% of recycled fibers to be mixed into new garments without compromising quality [11]. Closed-loop recycling is possible for pure cotton, but not for cotton that has been “dyed, treated or blended with other materials.” [11] For synthetic fibers, closed-loop recycling is far from commercially viable [11].

While H&M has made meaningful progress in achieving its mission of sustainability, it remains to be seen whether it can truly succeed in closing the loop for fashion or is simply employing greenwashing tactics to capitalize on the growing contingent of environmentally-conscious consumers.

Word Count: 716

Sources

[1] James Conca, “Making Climate Change Fashionable – The Garment Industry Takes On Global Warming,” Forbes, December 3, 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesconca/2015/12/03/making-climate-change-fashionable-the-garment-industry-takes-on-global-warming/#32482c17778a

[2] H&M, 2011 Annual Report, pg 10 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/en/Annual%20Report/Annual_Report_2011_P1_en.pdf

[3] http://www.hm.com/us/garment-collecting

[4] H&M, Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015, pg 87 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/masterlanguage/CSR/reports/2015%20Sustainability%20report/HM_SustainabilityReport_2015_final_FullReport.pdf

[5] H&M, 2015 Annual Report, pg 37 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/masterlanguage/Annual%20Report/Annual%20Report%202015.pdf

[6] H&M, Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015, pg 93 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/masterlanguage/CSR/reports/2015%20Sustainability%20report/HM_SustainabilityReport_2015_final_FullReport.pdf

[7] H&M, Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015, pg 99 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/masterlanguage/CSR/reports/2015%20Sustainability%20report/HM_SustainabilityReport_2015_final_FullReport.pdf

[8] H&M, Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015, pg 98 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/masterlanguage/CSR/reports/2015%20Sustainability%20report/HM_SustainabilityReport_2015_final_FullReport.pdf

[9] H&M, 2015 Annual Report, pg 39 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/masterlanguage/Annual%20Report/Annual%20Report%202015.pdf

[10] H&M, Nine-month report, pg 1 http://about.hm.com/content/dam/hmgroup/groupsite/documents/en/cision/2016/09/1789234_en.pdf

[11] Jared T. Miller, “Fast Fashion is Creating An Environmental Crisis,” Newsweek, September 1, 2016, http://www.newsweek.com/2016/09/09/old-clothes-fashion-waste-crisis-494824.html

Interesting post, Mary! I never knew the impact of the fashion industry on carbon emissions! I’m curious if H&M can take a page out of Ikea’s book and require that their suppliers also maintain a level of sustainability in line with that they are trying to achieve. Also, as an H&M shopper, I have seen their recycling program, but being ignorant of the impact that the fashion industry is having on the environment, I have never considered participating. I think that H&M needs to do a better job of explaining to their shopper why it’s so important to recycle their clothes and at the same time, find ways to use more than 20% of recycled clothing through an increase in R&D.

H&M has, as far as I know, innovated in the fast-fashion market, with its Garment Collecting Program that enables customers to recycle their old clothes and home textiles at store. As it is mentioned in the post, this is also a clever way to promote more sales to these customers, through the distribution of coupons. However, I believe that this measure, combined with an increase in the usage of “green” raw materials, can have a significant impact. I deem that, in the process of returning their old clothes and buying new, more sustainable ones, H&M can raise awareness for the importance of being “green”. By promoting “greener” customers, H&M will also be able to influence how these customers behave regarding other fast-fashion brands, and thus have an impact that exceeds what it is doing individually at H&M. The question is – will H&M live by its message and continue to work with an increasing proportion of eco-friendly raw materials.

As we saw with the IKEA case, its indeed challenging for growing companies to balance sustainability efforts with the impact of their growing business on the health of the Earth. Prior to reading this piece, I didn’t know that fashion garments produce %400 more carbon emissions per item per year compared to garments worn more than 50 times. As someone who rarely buys clothes, this is an alarming number and makes me think twice about buying on a more regular basis.

Its also interesting that consumers rarely know the impact they have based on their purchasing habits. Not until reading this article did I realize the huge influence I can have on climate change. One way I can reduce my footprint would be to buy less clothes, which H&M would not want me to do. On the other hand, H&M could continue to change the way they do business. Understandably, H&M as a business wants to grow into new markets and continue to introduce novel product lines. In addition to meeting these goals, I think they have clear opportunities to push innovation to help them limit their global emissions per year. I love the idea of the recycling program. Like you mentioned, it’s a great way to incentivize customers to return to the store to purchase new products, but it also helps the company deal with the ramifications of the increasingly shorter buying cycles.

I wonder what R&D efforts are going into rethinking the way recycled fibers are being incorporated into new garments. If they are able to incorporate more than 20% without reducing quality, this may be another way for H&M to make strides as industry leaders.

Thanks for bringing to light the fast fashion industry’s impact on the environment. I’m curious to know which facets of the fashion industry operations contribute the most to climate change. My bet is in manufacturing, which makes the prospect of closed-loop production most promising. However, it appears that progress in this type of production is greatly hampered by tradeoffs between sustainability, cost, and quality. The one company that I think is a real leader in this space is Patagonia – they have been doing closed-loop recycling for synthetic textiles like elastane-nylon blends. To chemically process polyester into core components and spin it back into polyester thread is, as you’ve mentioned, very expensive. The process only works with high-quality polyester textile (Patagonia’s own fleeces) as input and isn’t viable with cheap polyester textiles typically used in fast-fashion. But the important distinction here is that Patagonia has been implementing this method out of principle, not for profit. I wonder how much H&M can move the needle without acknowledging that sometimes they just have to do what’s right and not just what’s right for profitability.

This was fascinating! I may start shopping at H&M! While I applaud their efforts, I wonder what is the environmental impact of recycling clothes. The 20% that gets recycled would need to be re-treated, which may decrease its positive environmental impact. Furthermore, what happens to the clothes that can’t be recycled? Does the company simply destroyed them? If so, the overall impact of this specific strategy may not be very significant. However, a something is better than nothing even if it is just to bring more consumers into the stores…

Great post, Mary! I also wrote about H&M. We seem to share the view that H&M is coming up with innovative solutions, but is also part of the underlying problem, which is people consuming far too many clothes. You mention in your post that a garment can only be made with 20% recycled fibers. This is not necessarily true anymore, which is a good thing! For a synthetic fiber, like polyester, you can make a garment from 100% recycled fiber. For a natural fiber, like wool, cashmere, or cotton, the fiber length gets shorter each time a garment is recycled. This means, you either need to spin a thicker/coarser yarn, or you need to blend in longer (virgin) fibers, to maintain a comparable yarn quality. This is probably where the 20% statistic comes from. A few companies (ex: Evernu, Lenzing) are also researching how to use recycled cotton pulp (instead of wood pulp) to create a fiber similar to Tencel, which is a bio-based synthetic, created using a closed loop chemical process. No one has found the perfect solution yet, but there’s definitely innovation happening. All that being said – the real problem is way too much consumption.

This was super interesting to read – thanks for sharing! It seems like H&M is taking a lot of logical steps to try to be more sustainable, but the whole concept of fast fashion and pushing high volume sales over short sale cycles might be fundamentally at odds with truly being sustainable. I wonder if there’s more H&M can do to set concrete targets for the percentage of clothing they produce with recycled materials, organic cotton, etc. Similarly to what we saw with IKEA, it’d be interesting to see what H&M’s mix of recycled material inputs would be if they drove to specific targets focused on the environmental impact as opposed to volume or profit.

Great post! H&M is such a good parallel to IKEA, which also is striving for sustainability while creating a fundamentally unsustainable product. Your post raises some really important questions about the degree to which a company that has more or less created the disposable fashion category can really ever call itself sustainable. While its efforts to go green are commendable and its scale makes its impact significant, you have to wonder as a consumer if they can ever really do enough to reverse the negative impact they have already made by introducing this fast fashion concept to the public.

It’s impressive that H&M has put so many initiatives into place to build a more sustainable supply chain. They’ve made an effort to attack the issue on as many fronts as possible, at both the demand and supply levels: setting ambitious sustainable sourcing goals, launching an eco-friendly sub-brand / collection, the trade-in program, energy efficiency within stores, etc. The eco-friendly collection is especially creative and I will be interested to see how this effort does over the years. Giving consumers the option in-store to either buy eco-friendly or non-eco-friendly clothes will be an interesting case study or proxy for how much the cause truly resonates with consumers. My hunch is that this will remain a niche collection, if it survives at all, but maybe if public opinion and media pressure on these climate change and sustainability issues gain steam, we will see consumers actually make that choice.

I love H&M and shop there all the time so I definitely appreciate your outline and lay out of the big picture regarding sustainability (great read!). I must say I never had the opportunity to participate in the Garment Collecting Program so I agree with some comments above that H&M would greatly benefit from continuously and aggressively educating their customers on their sustainability initiatives.

In addition, I do see parallels between H&M and IKEA in terms of the tradeoff or tension between increased sustainability and expansion. I am curious about how they manage the relationships across the supply chain. With IKEA’s constant evaluation of suppliers in mind, I wonder if H&M operates the same way when it comes to the supplier factories and focus on water management? How often do they evaluate their suppliers and on what metrics?

Thanks so much for shedding light into this topic, Marry. To be honest, I have a bit of trouble appreciating H&M’s initiatives and would be more inclined to put them into the “greenwashing” category. I think coming up with water and power reduction measures in a fundamentally unsustainable business model that is based on the artificially accelerated consumption of clothes and the underlying resources, and then calling yourself sustainable is quite deceiving. And while I do not have deeper information on the efficiency of their recycling systems, it is very often the case that the energy input used to recycle one item ends up being higher than the actual footprint of producing an entirely new item. I think your post is very valuable because its mere existence is a step towards the solution – it contributes to our (H&M) consumers’ better understanding of the issue and gradual shift towards “slower fashion” brands.

I meant Mary with one single r 🙂

It’s very interesting to read about the initiatives of H&M has taken to tackle climate change, including supply chain integration and water-saving. Other than the changes made on manufacturing side, I think, H&M can fully capitalize its advantage being in the fashion and apparel business. One thing popped to mind is product innovation. Clothes made from eco-friendly materials without sacrificing the quality and design would certainly appeal to the mass market. With product innovation, it’s also possible to drive cost down and hence allow more investment into the initiative within the system to reduce carbon footprint. (http://www.elle.com/fashion/a12694/hm-eco-friendly-fashion-ever-manifesto/)

Thank you for such an interesting and insightful article! As a frequent shopper at H&M, I’ve never realized how significant of an impact H&M and other fast-fashion companies have on carbon emissions and climate change. In fact, I was never aware of the Conscious Collection and the Garment Collecting Program.

I wonder how the material costs for Conscious Collection compare to those of other collections. If the percentage of material costs to revenue for Conscious Collection are indeed noticeably higher than those of other normal collections, what would H&M do? Would it still be incentivized to continue producing Conscious Collection?

In addition, it would be interesting to see how customers react to Conscious Collection. As a brand that focuses on affordability and trendiness, do H&M’s target customers really take into account the environmental-friendliness factor as part of the customer value propositions when they make their purchasing decisions?