Get Em While They’re Hot: Dynamic Ticket Pricing in Major League Baseball

How professional baseball teams borrowed a strategy from airlines and musicians to strike back against secondary ticket brokers like StubHub.

In a highly competitive world, the pressure is on for businesses to capture the eyeballs and wallets of their customers. Baseball teams are no exception to this phenomenon. With a 162-game season, almost double the length of other major sports, ticket revenue is an enormously significant part of the business of baseball compared to sports like the NFL which rely more heavily on TV contracts. In this context, how can baseball teams maximize their revenue?

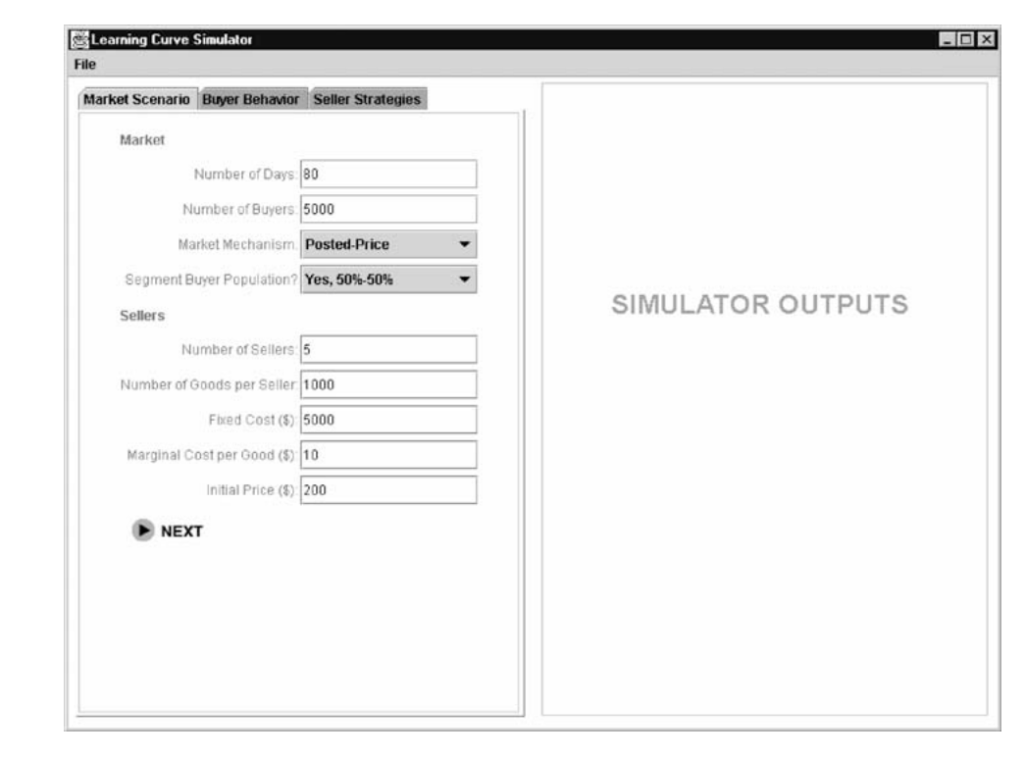

Well, step one is to sell more tickets. But another option which is increasingly becoming relevant is to adjust pricing based on customer demand, the same way that airlines have priced tickets for years. Dynamic (or Variable) Ticket Pricing is a machine learning process which refers to periodically adjusting prices based on the factors affecting individual events.1 With secondary ticket marketplaces like StubHub leveraging pricing discrepancies based on customer demand as their core business model, it only makes sense that content providers (in this case, baseball teams) compete for fan dollars using the same strategy as that of secondary ticket brokers in order to maximize their own revenue.

Ticketing Ecosystem Map (7)

Why does a baseball fan choose to attend one game versus another? In 2009, the San Francisco Giants were the first team to use dynamic ticket pricing (DTP). They recognized that fan demand for each game depends on a number of inputs including team/ player performance, day of the week, opposing team, weather and more. In contrast to the traditional practice of setting prices before the season and not adjusting them during, the Giants started using machine learning to dynamically adjust prices during the season to account for fluctuations in demand. As a result, they were able to generate an additional $500,000 in incremental revenue in 2009 and had an overall revenue increase of 7% in 2010.2

It is important to recognize that since DTP is a relatively new phenomenon, baseball’s short term and long term goals differ in their implementation of this pricing strategy. This issue is complex because pricing decisions are not made in a vacuum. First, a fan’s perception of a team is impacted by the prices the team sets. The team-fan relationship is critical to maintain since sustained strong team performance on the field is rare. Therefore, teams need to keep fans happy so that they continue to show up whether the team plays well or plays poorly. Having a reputation for “high” ticket prices does not lead to strong team-fan relationships. Second, fan demand is inherently uncertain. There is a fixed, finite amount of inventory with a number of variables that can cause major swings in consumer demand.3

Given this complexity, teams are applying machine learning to dynamic ticket pricing in a conservative manner in the short term. For example, the LA Dodgers recognize that season ticket holders have relatively higher importance than individual ticket buyers. There would be significant brand damage if they were to sell tickets to a game to season ticket holders at a higher price than to individual ticket buyers due to a drop in demand.4 The Dodgers are using the recommendations of the machine learning algorithms as a starting point to their ticket pricing, but ultimately maintain human control over final prices to ensure that they are never jeopardizing their most important fan relationships with pricing practices which could be perceived as “unfair.”

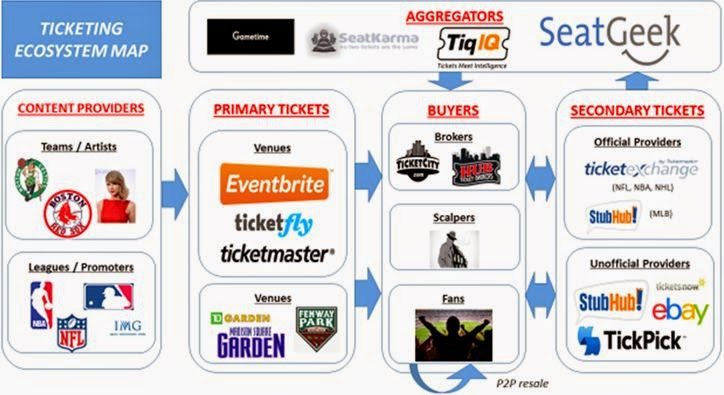

By contrast, in the long term once teams have more experience with dynamic ticket pricing and specific data on their fanbase’s reaction to it, teams plan to incorporate simulation-based algorithms to minimize the need for human intervention in their pricing. One such algorithm is the “Learning Curve Simulator” which imitates real market conditions by matching randomized game variables with a group of buyers. Each buyer is comparing the ticket sales price with his or her individual willingness to pay and is making a buying decision accordingly.5 By running these simulations, teams can increase the accuracy of DTP.

Learning Curve Simulator (5)

Regarding other steps, baseball teams should look to other industries and use what works for them while still recognizing the unique intricacies of sports which require differentiated strategies. For example, Taylor Swift is using higher priced face value tickets in combination with a “Verified Fan” program to ensure tickets aren’t being scooped up by scalpers and resold to her fans for profit. On the positive side, these steps helped her Reputation tour generate 15% more revenue than her previous tour.6 However, while these shows created more revenue, there were fewer sellouts. Sellouts in sports can be more significant to fan experience than sellouts in music which is why implementing this strategy in baseball would be risky.

T Swift Reputation Tour (8)

What impact would your favorite team or artist using dynamic pricing have on your loyalty to them? Do you see secondary markets as a friend or foe to teams/ artists?

(Word Count: 799)

- Rascher, Daniel A.; McEvoy, Chad D.; Nagel, Mark S.; and Brown, Matthew T. (2007), “Variable Ticket Pricing in Major League Baseball”. Kinesiology (Formerly Exercise and Sport Science). Paper 6. http://repository.usfca.edu/ess/6

- Shapiro, Steven L, and Joris Drayer, (2012). “A New Age of Demand-Based Pricing: An Examination of Dynamic Ticket Pricing and Secondary Market Prices in Major League Baseball.” Journal of Sports Management, pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9ebf/87dadc294b14ae68615f50f168faf57b6b66.pdf.

- den Boer, Arnoud V (2013). Dynamic Pricing and Learning: Historical Origins, Current Research, and New Directions. Universite of Twente.

- Parris, D. L., Drayer, J., & Shapiro, S. L. (2012). Developing a pricing strategy for the los angeles dodgers.Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21(4), 256-264. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1324536397?accountid=11311

- Morris Dimico, Joan, et al (2003). Learning Curve: A Simulation-Based Approach to Dynamic Pricing. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Steele, Anne. “Why Empty Seats at Taylor Swift’s Concerts Are Good for Business.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 15 May 2018, www.wsj.com/articles/why-empty-seats-at-taylor-swifts-concerts-are-good-for-business-1526385600.

- Fang, Jane; Quinn Matt. (2017), “Evolution of the Ticket: An Ecosystem Analysis for Gametime United”. http://launchingtechventures.blogspot.com/2015/04/evolution-of-ticket-ecosystem-analysis.html

- [Image] http://www.soundslikenashville.com/culture/the-five-coolest-things-we-saw-at-taylor-swifts-reputation-tour-stop-in-nashville/

Great article – very timely study following the TOM field trip last week. Personally, I have no problem with Dynamic Pricing. For the teams, I think it helps to incentivize buying early – whether for season packages or early purchases for individual tickets – which enables teams to predict demand and scope the season, and for individuals, it helps you to choose the games at your price point. I’m not going to pay a lot of money to watch a bad team play the Astros (go ‘Stros!), but I will pay to watch a good team play them. I will pay more for the better experience, and I want the stadium to be sold out for that game. I think Dynamic Pricing helps to increase the turnout at cheaper games and get the people who are willing to pay for the experience into the expensive ones.

Great read! Very interesting to see how teams are using a combination of machine learning and human intervention to dynamically price tickets. It makes sense that these teams have the goal of removing the human element here, but I wonder if they can really get to a state where no human intervention is needed. As we see with airlines, ticketing is a complication practice and still requires a tremendous amount of human interaction, especially when things go wrong. The final question you pose is a great one. As a consumer of sports, music, and entertainment, I generally see secondary markets as causing more harm that good. With tickets selling out in seconds and scalpers inflating the price on these markets, it does feel like some policing is necessary.

Super interesting. Full disclosure – I know very little about baseball – but I wonder how this approach to pricing would affect revenue for teams when they perform poorly, or when other factors affecting the algo like weather underperform. Assuming that fans have heterogenous preferences on what makes a game “worth it” (good weather, strong team performance, etc), and that they can’t predict how these factors will play out in the future, they may wait for prices to go down before they make purchases, reducing overall revenue for the team – for example, if I care about team performance but not weather, but I assume the “price” of a good weather ticket is baked into the pre-season price, under dynamic pricing I may wait until I see good team performance and bad weather so get my ticket at a discount. Even putting preferences aside, any user that expects a team to do worse than the pricing reflects would be better off waiting to buy their ticket. Have we seen examples of how dynamic pricing plays out when a team has especially bad scores, poor weather, etc?

Great piece! It would be interesting to see how dynamic pricing models adapt to usage in price discrimination strategies (such as pricing season-tickets vs. regular tickets). Completely agree that using DTP will inevitably increase stadium utilization by ensuring that ticket prices are fully reflective of customers’ willingness to pay (e.g. a customer may buy a ticket for a less competitive game simply because it is priced so low, whereas they previously wouldn’t have if the ticket was priced regularly). I do worry that the DTP may lead teams to completely outprice certain extremely competitive games. Stadiums typically fit 40,000 + spectators. And if a small set of outliers bids up the ticket price significantly, it may limit the team’s ability to sell out the remaining seats. I wonder how responsive DTPs can be to daily swings in demand, in order to rectify this issue?

The secondary ticket market is a vital part of ensuring that anyone who would like to go to can ultimately attend whatever event they would like to attend — if they are willing to pay market price. Teams, musicians, and other content providers who issue tickets have every right to want to capture more of the value that falls to the secondary ticket market. But imposing the “verified fan” program to do so and preventing the tickets from being sold on the resale market runs counter to fans’ wishes — ultimately, fewer fans have the possibility of attending a game if attendance is restricted to only the initial ticketholder. Content providers wishing to capture more of the resale market value would be better off hosting their own independent resale platform and charging higher fee percentages — while this would frustrate sellers, it discourages profit-seeking in the same way that the “verified fan” program does while also ensuring that the market remains able to set the final price for the ticket.