Driving into the Unknown: Ford Motor Company and NAFTA

Potential changes to NAFTA could threaten Ford's supply chain

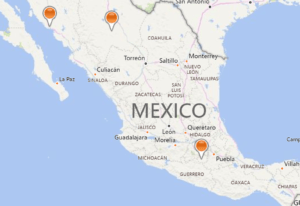

The North American Free Trade Agreement entered into force on January 1, 1994, eliminating most barriers to free trade between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. [1] Ford Motor Company was one of many companies able to benefit by optimizing its manufacturing operations without the distortion of tariffs and other customs barriers. Today the Company has three manufacturing facilities in Mexico:

Ford’s Manufacturing Operations in Mexico [2]

There are several benefits to Ford of manufacturing in Mexico. The country has a relatively skilled and low-cost labor force, is well located geographically to ship to the U.S. or South America, has wide ranging trade agreements, and has government policies promoting exports. [3] There are also an increasing number of Mexican graduates from engineering and technical schools which have expanded the pool of skilled labor. [3] The country’s “maquiladora” program also allows for duty-free importation of raw materials, components and equipment needed in the manufacture of goods for subsequent export. [4]

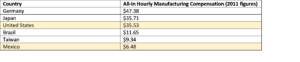

Hourly Manufacturing Compensation by Country

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics [5]

The future of NAFTA, however, has become increasingly unclear, and may change how Ford and its peers view the benefits of manufacturing in Mexico. The current U.S. administration has highlighted two key areas that may change in the future. The first are changes to the rules of origin. Rules of origin govern what share of a car must be sourced from NAFTA countries (currently 62.5%) to qualify for NAFTA benefits. [6] Either an increase in that share or creating NAFTA country specific portions of that share could add substantial complexity and cost to the supply chain. [6] Alternatively, an import tax could be instated which would entirely change the economics of manufacturing in Mexico for import into the United States. [7] While there are many benefits to manufacturing in Mexico, Ford must be wary of the impact U.S. isolationism could have on NAFTA and the economics of production in Mexico.

In the short term, as a leading U.S. corporation, Ford has a voice it can contribute to the conversation. Ford’s President of the Americas, Joe Hinrichs, has suggested focusing NAFTA changes on reducing foreign exchange manipulation and streamlining safety and other vehicle standards across the three countries. [8] Ford’s former CEO Mark Fields was also vocal about the negative impacts of isolationism and indicated the company was in direct communication with the Trump administration on the topic. [9]

In the medium term, Ford is adjusting its decisions on capital allocation. In 2016, Ford announced it would build a $1.6 billion plant in San Luis Potosi in Mexico to build its Ford Focus model and create 2,800 jobs. [10] That decision came under attack from then-presidential candidate Donald Trump. In 2017, the Company announced it would instead be building the Focus in China, where it could save $1 billion in investment costs. [10] The move underscored the Company’s reluctance to invest additional production in Mexico amidst uncertainty and the increased interest in low-cost manufacturing options outside North America altogether.

There are additional steps the Company could take in the short and medium term to address the isolationism concern. The first would be to build a stronger coalition of companies to support NAFTA. While certain automotive companies have banded together in lobbying efforts, Ford could work to expand this further to incorporate a broad consortium of industries affected by changes to NAFTA. In the meantime, the Company could also continue to focus its North American investments in the United States to protect against changes that could impact the economics of locating manufacturing in Mexico or Canada. In the longer-term, the Company should work to diversify itself away from the United States. In 2016, 45% of Ford’s car sales were in North America versus 24% for the global industry. [11] If the Company can further market its cars in growing international markets, it can reduce the impact and risk of U.S. isolationism on the Company at large. Ford may ultimately be best served by taking a long-term view and focusing on the lowest cost manufacturing locations with the best export conditions with the goal of being competitive on a global basis – even if it means potentially being less competitive in the U.S. market in the short-term.

Questions to consider: What is better for Americans, more manufacturing jobs in the U.S. or lower cost vehicles? Should Ford be investing in Mexico amidst uncertainty with NAFTA? With the potential for major administration changes in the U.S. every four years, how should companies think about the potential for considerable changes in trade policy on their supply chains?

(761 words)

[1] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),” https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/north-american-free-trade-agreement-nafta, accessed November 2017.

[2] Ford Motor Company, “Operations Map,” https://corporate.ford.com/company/operation-map.html, accessed November 2017.

[3] Coffin, David. Passenger Vehicles. Industry and Trade Summary. Publication ITS-09. Washington, DC: U.S. International Trade Commission, May 2013.

[4] Team NAFTA, “NAFTA and the Maquiladora Program,” http://teamnafta.com/manufacturing-resources-pages/2016/4/18/nafta-and-the-maquiladora-program, accessed November 2017.

[5] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Components of Hourly Compensation Costs in Manufacturing, U.S. Dollars, 2011,” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/ichcc.t03.htm, accessed November 2017.

[6] Gabrielle Coppola, “Auto Industry Warns Trump Is Proposing ‘Lose-Lose’ Changes to Nafta,” Bloomberg News, October 11, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-11/auto-industry-warns-trump-proposing-lose-lose-changes-to-nafta, accessed November 2017.

[7] Brad Tuttle, “Lots of Your Favorite Things Could Cost More if Trump Adds a 20% Mexican Import Tax,” TIME, January 27, 2017. http://time.com/money/4651919/trump-import-tax-mexico-build-wall/, accessed November 2017.

[8] Michael Martinez, “Ford’s Hinrichs on how to improve NAFTA,” Automotive News, May 1, 2017. http://www.autonews.com/article/20170501/OEM11/305019958/fords-hinrichs-on-how-to-improve-nafta, accessed November 2017.

[9] Tim Higgins, “Ford CEO Wary of Trump’s Talk About Tariffs and Nafta,” The Wall Street Journal, November 15, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ford-ceo-looking-forward-to-working-with-president-elect-trump-1479234267, accessed November 2017.

[10] Brent Snavely and Grace Schneider, “Ford to import Focus from China instead of Mexico,” Detroit Free Press, June 20, 2017. http://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/ford/2017/06/20/ford-import-focus-china/411600001/, accessed November 2017.

[11] Ford Motor Company, 2016 Annual Report. (Dearborn: Ford Motor Company, 2017), p. 4.

The last question you raised, about how companies should think about supply chain initiatives given the four year election cycle, is fascinating and deserves a much more lengthy conversation than just this one comment. Given the huge potential for loss if the executive branch can unilaterally change the economic terms that would have previously made an investment attractive, I think it’s very important for managers in private firms to be well informed on the specifics of those political and regulatory risks.

In this case, the risks seem to hinge on the question of whether the President actually has any authority to withdraw from NAFTA, and if so, what the effects would be. While the executive branch is typically understood to have authority in the context of foreign relations, most scholars would agree that Congress has constitutional authority over trade with other nations. NAFTA has some interesting characteristics that make the debate more complex. On the one hand, much of NAFTA was implemented by Congress through a statute, so if that were the end of the story, Trump would have no authority to change the U.S.’s status in terms of its relation to NAFTA. Some scholars think that is the end of the story, and we don’t yet know who is right. At the same time, NAFTA includes a provision allowing a party to withdraw from NAFTA six months after notifying the other parties. So under one scenario, it might be possible for Trump to withdraw from NAFTA according to that provision, but we would then be left with a statute that implemented much of what NAFTA actually contains. If you take a cynical perspective, that could mean that we might continue to be bound by this statute (until Congress got rid of it), while we no longer participate in NAFTA as a party and therefore no longer receive benefits from such participation (because Canada and Mexico would not have to honor the agreement in their relations to us except to the extent that they implemented NAFTA in their own internal governance). That is an unlikely scenario, as Congress would probably (hopefully?) step in at some point to either prevent this kind of thing from happening or clean up the mess if it did happen.

Here are some other people’s take on this question:

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/10/26/16505508/nafta-congress-block-trump-withdraw-trade-power

http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/international-affairs/346744-trump-cant-withdraw-from-nafta-without-a-yes-from

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/04/trump-nafta-withdrawal-order/524463/

Sorry for going down that rabbit hole, but my main point is that managers making huge investment decisions should understand the political risks and the different scenarios that could arise out of these complex international relations.

I find your first question about whether Americans benefit from more manufacturing jobs in the US or lower cost cars a fascinating one. I read an article last year in the New Yorker that argues that despite Donald Trump’s rhetoric, jobs will not actually return to the US when companies such as Ford return their manufacturing plants here. Rather than creating new jobs, at least in the long-term these on-shore investments are driven by automation and the goal of removing as many humans as possible from the assembly process. As the New Yorker article states, “salaries aren’t an issue without the salaried” and argues that discussion of withdrawing from deals such as NAFTA in order to bring jobs back to the US is “like applying leeches to a head wound.” Since the tasks that are moved off-shore are often the most basic ones, these tasks are relatively simple to automate and therefore moving these jobs off-shore “is often just a “way station” on the road to eliminating them entirely.” I would highly recommend giving the article a read — it really opened my eyes to the ways in which automation will (and already is) impact manufacturing jobs: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/12/19/our-automated-future.

I agree with Francie that your first question (on whether more manufacturing jobs or lower cost vehicles are better for Americans) is exceptionally interesting, and merits further discussion. The answer is at the nexus of tends in digitization and isolationism. As many of the articles in the “TOM Challenge” discuss, digitization is transforming supply chains and automation is negating the need for human involvement in many areas of the production process. Tesla, for example, is very focused on increasing automation in its factories, and recently purchased a process automation firm, Grohmann Engineering. [1] If manufacturing processes become increasingly automated, significant up-front capital expenditure will be required, but costs will ultimately be driven down over time. Given this trend, in order for Ford to move more factories within the U.S. to avoid risks associated with changes to NAFTA, it would have to believe that Americans would value cheaper cars over more manufacturing jobs.

However, I do not believe that 100% automation will be fully realized in the short- to medium-term. The last major change to car manufacturing was the invention and implementation of the Toyota Production System (TPS) that we studied in class, which has been adopted (in whole or in part) by most major auto manufacturers over the course of several decades. [1] I think a fully automated production process may take a similarly long period to be so widely adopted.

Therefore, Ford will need to weigh the probabilities of outcomes of NAFTA negotiations against that of the realization of fully automated production processes as it decides where to locate its future manufacturing plants.

Sources:

[1] Matthew DeBord, “Tesla’s future is completely inhuman — and we shouldn’t be surprised”, Business Insider, May 20, 2017, http://www.businessinsider.com/tesla-completely-inhuman-automated-factory-2017-5, accessed November 2017.

Ben, thank you for the informative read on an increasingly important topic. The media has continued to report (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trade-nafta/nafta-talks-hit-wall-as-mexico-canada-push-back-on-u-s-demands-idUSKBN1DL0FL) that NAFTA talks are stalling, and while conversations are to continue into next Spring, achieving the “rebalancing” that the Administration is proposing is going to be significantly challenging for Mexico and Canada. This is further complicated by the fact that the Mexican general election is to take place on July 1, 2018, which introduces incremental uncertainty to equation.

While I agree with what has been said that a long-term perspective should be held (and, as a Canadian, had some of my worries assuaged by Sam’s commentary), I do think the uncertainty surrounding U.S. relations with Mexico in the short term warrant the decision to avoid investment in Mexico. Your point on diversification is well taken and I believe that your suggestion about considering export conditions when making investment decisions is very sound, but that strategy is likely best kicked off when the company has a clearer line of sight into the regulatory landscape (and potentially, more of an ability to effectively and productively lobby the relevant parties to support its decision-making).

As you mention well, if NAFTA current agreements were modified or suspended, there are implications for Ford’s plants in Mexico. Impacts would be both in the increased production costs and the increased tariffs on the final product. Therefore, I believe the best strategy for Ford is to use its current plants in Mexico to supply other markets than the US. How to do this?

An interesting plan of action is to partner with other car manufactures that don’t have plants in Mexico but have high demand of cars from central and south america, and at the same time have plants in the US. The deal would then be shifting part of Ford’s US production to the other manufactures plants and vice versa, and use Ford’s plants in Mexico only for Mexican demand and international non-US demand (Countries is Latin America And South America).

These are the type of strategies that car manufacturers are implementing with the Brexit. Nissan for instance has important production in the UK, but this January the Nissan Micra became the first Nissan passenger car to be produced in a European Renault plant to face potential impact of Brexit. There is an interesting article from a classmate of another section related to this topic: https://d3.harvard.edu/platform-rctom/submission/nissan-at-the-brexit-poker-table/#comment-14786

Thanks for this interesting discussion, Ben. The question of whether the move to China, rather than Mexico or elsewhere, was correct is an interesting one. At the heart of the question is a debate of probabilities. Is the Trump administration more likely to unfavorably change NAFTA or trade relations with China? For Ford, the probability of changes to NAFTA, combined with other opportunities offered by China, was compelling enough. With all the rhetoric from Washington, it’s ironic that Ford pulled out of Mexico, only to overlook the US and invest in China. Interestingly, in 2016, the US trade deficit with China was nearly $350B (https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html). Contributing to this deficit are 25% import tariffs and additional value-added taxes on US automobiles imported into China. In contrast, foreign automakers pay only 2.5% import taxes to reach the US market (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/03/20/a-slap-in-the-face-to-u-s-taxpayers-most-vehicles-imported-from-china-are-made-by-an-american-company/?utm_term=.0fbf74e43652). Moreover, Chinese subsidies on eco-friendly cars often exclude foreign-built vehicles, furthering dampening the prospect of closing this trade gap. Given the harsh language against China by Trump, Ford may come to regret its decision to pass on investing in other countries. In the end, it may well have been better served by following your recommendation to further diversify its global presence elsewhere.

As your article suggests, NAFTA’s current structure reduces the complexity of trade within North America. For example, tracking a car’s parts regionally would add an additional layer of reporting bureaucracy that would ultimately raise costs. [1] In the presence of NAFTA, the North American auto industry has been able to maintain stability, despite the rise of competition from emerging economies. [2] Given the rise in complexity, I am not convinced that in the absence of NAFTA, companies such as Ford would have no other option but to keep manufacturing jobs in the US. As international trade history would suggest, a rational firm would look for opportunities elsewhere. In this case, the optimal option is likely to relocate plants to Asia (and in particular, China). [2] This is simply because higher tax incentives may not be enough to offset cheaper real estate and labor costs in certain developing economies. [3] So whether it is China or elsewhere, companies such as Ford will have to explore relocation options to be able to provide low prices to their consumers and remain competitive in a fast automotive landscape – making the prospect of keeping automotive jobs in the US seem quite bleak.

[1] Coppola, Gabrielle. Auto Industry Warns Trump Is Proposing ‘Lose-Lose’ Changes to Nafta. Bloomberg. October 2017.

[2] Siekierska, Alicja. Why U.S. push on NAFTA rules of origin for auto industry may backfire and benefit Mexico. Financial Post. September 2017.

[3] Black, Thomas. Even a Nafta Collapse Won’t Keep Companies From Moving to Mexico. Bloomberg. October 2017.

Great insight, I appreciate using Ford as a case study for what many manufacturing companies are surely debating today. I agree with your argument that Ford should focus on the long-term view of low cost manufacturing. However, I believe that in the long-term China may not actually be cost effective due to the rising labor costs and additional transportation costs for the 45% of Ford sales in the U.S. Labor costs in China have more than quadrupled since 2006 and BCG estimates that regions of the U.S. may already be within 10-15% of the wages in China. [1]. On top of that, manufacturing domestically saves development costs, trade costs, and as Vanessa mentioned, increased automation will likely further reduce the wage parity between the U.S. and China. Thus, for these economic reasons as well as the trade risks Eugene highlighted, I am hesitant to back Ford’s decision to move to production to China.

[1] Morris, David Z. “Will tech manufacturing stay in China?” Fortune, 27 Aug. 2015, fortune.com/2015/08/27/tech-manufacturing-relocation/.

As Francie pointed out, the question about whether Americans benefit from more manufacturing jobs in the US or lower cost cars is very interesting. I do think that she makes a great point by explaining that bringing manufacturing plants back to the US won’t create more jobs, because the future of this plants is to have an automated assembly process. In addition, and going back to your question, I believe that if the automotive industry cannot protect NAFTA, Americans would be the most affected group by having to pay for more expensive cars.

In a country where most people own and use a car (1.3 people per car [1]), where distances are quite long and not necessarily covered by public transportation, and where transportation is the third heaviest component of the household expenses [2] (representing approximately 15% of the CPI basket), the increase in car prices would have a devastating effect in a family’s economy.

A different, but worse outcome, would be for companies to produce and to offer cheaper cars, by lessening their quality standards. This would probably reduce the life of the vehicle and generate additional expenses, decrease safety standards of the vehicles leading to more road accidents, or increase the emissions and collateral effects on the environment.

Hopefully the future of NAFTA becomes clearer in the coming months, and includes positive news for the automotive industry.

[1] Daniel Tencer, “Number Of Cars Worldwide Surpasses 1 Billion; Can The World Handle This Many Wheels?”, Huffpost, February 19, 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2011/08/23/car-population_n_934291.html , accessed November 2017.

[2] BMI Risk Report, “United States Country Risk Report – Q1 2018,” Business Monitor International, ABI/INFORM via ProQuest, accessed November 2017.

Great essay, Ben, and very interesting to me given that I grew up in Michigan surrounded by the impact of the American auto industry. Your point around where cars are made and sourced is good, and so complex. You mention the cost of manufacturing outside of the United States or Mexico, and the need to diversify where cars are sold, which I agree with. As income rises across the globe (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG) , more households may be able to afford cars. However, given trends around urbanization (http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/world-urbanization-prospects-2014.html), we may also see trends in which fewer people (young people in particular) are buying cars because they live in highly populated, dense areas that have other forms of transportation.

The issue of optics is another things I would raise. I remember reading and being surprised to see that Toyota is actually a very US centric company when it comes to producing their cars (https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/cars/2016/06/29/survey-top-made–usa-cars-toyota-honda/86510052/). Despite that, Toyota is still seen as a foreign car brand and the overall perception in some areas where “American made” is valued is very negative towards Toyota. I think Ford, as they diversify their manufacturing and sales, should be cognizant of the goodwill that comes in the US from being an American brand and be cautious in where they choose to locate and any sort of press that comes if they do move factories. Although many are used to cars being made in Mexico, I wonder if switching over to making more cars in China could lead to a reputational risk for such an iconic brand.

Very thought-provoking write-up. Most critics of NAFTA cite two statistics to illustrate the “negative” impact of the agreement: (1) the swing in the US-Mexico trade balance from a $1.7B surplus in 1993 to a $64B+ deficit in 2016 and (2) the fact that the U.S. auto sector has lost 350k+ jobs since 1994 while employment in the Mexican auto industry has increased by 400k+. However, these statistics do not capture the full picture. One must recognize that while the burden of NAFTA has been highly-concentrated in specific industries like auto manufacturing (as mentioned above in several comments, an argument could be made that jobs would have been lost to automation regardless), the benefits of NAFTA have been distributed more widely across society. A 2014 PIIE study of NAFTA effects (https://piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/nafta-20-misleading-charges-and-positive-achievements) found that 15,000 net jobs are lost in the US each year due to the pact but that for each of these lost jobs, the economy gains ~$450k in the form of higher productivity and lower consumer prices. The risk inherent in this PIIE finding is that the NAFTA benefits (specifically, lower automobile prices) may still be accruing to the wealthier population….leaving displaced workers in difficult position – jobless or in a lower paying job and unable to recognize or experience NAFTA’s economic benefits.

Sources:

[1] https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/naftas-economic-impact

[2] https://piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/nafta-20-misleading-charges-and-positive-achievements

[3] https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c2010.html#2017

Thank you very much Ben! This is a very interesting essay. Regarding your first question about whether more manufacturing jobs or lower cost cars are better for US, I agree with Francie and Vanessa. Eventually, automation will significantly decrease need for human labor and companies will make their decisions regarding other key elements of cost structure. However, I believe that effects of automation will be observed in OEMs later than car manufacturers and in short term labor costs will play a significant role. For example, today more than 40% of parts used in compact Focus models are sourced directly from US. [1] However, new Focus plant in China will source significant part of parts from OEMs in Asia and lead to job losses in US. Although government officials tried to push car manufacturers to invest in US, so far it seems that this move just had an opposite effect. Moreover, in my opinion uncertainty in government policies will lead car manufacturers to accelerate automation and diversified manufacturing to minimize risks associated with change in trade agreements.

[1]. Shannon O’neil, “If NAFTA ends, Ford’s move to China just will be start”, American Quarterly, June 22 2017, http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/if-nafta-ends-fords-move-china-will-be-just-start, accessed November 2017

An interesting point on options that Ford has to de-risk its manufacturing options under the scenario that NAFTA gets the axe. Another angle on it that I’d be interested to read an opinion on is whether it might be advantageous for a company like Ford to pursue markets outside of the USA – shipping Ford cars made in Mexico to other countries entirely. Since the USA is responsible for just 25% of the world’s GDP (so says Google), there may be other ways to get their cars into the hands of consumers that don’t involve butting up against unfriendly trade regulations in the USA.

Very interesting read, thanks Ben. This made me think of some of the other protectionist measures under debate in the U.S., specifically the tariffs on imports that the U.S. steel and aluminum industries have been lobbying for over the past few years to combat alleged “dumping” by Chinese producers. While it would seem to me that imposing these tariffs would protect steel and aluminum jobs in the U.S., the Trump administration is dragging their feet, despite promising to implement the tariffs earlier this year (https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/26/business/trump-schumer-steel-aluminum-tariffs.html). In fact, it’s looking like foreign manufacturers are shipping more steel and aluminum into the U.S. to try to get ahead of any tariffs that may be imposed (steel imports jumped 20% since April), making the problem worse in the near-term as U.S. producers continue to lay off workers and close plants. It seems contradictory to me that the administration is so aggressively focused on the NAFTA topic to somehow increase U.S. jobs while ignoring other mechanisms and losing existing U.S. jobs in the process.

Ben,

Great stuff-thanks for sharing! I believe your first and third questions are deeply interconnected in this particular case. As many have pointed out, the number of jobs at stake in Ford’s shifts from Mexico to US production is small in both absolute and relative terms. Yet, a first-term elected official who must constantly be engendering support for re-election is incentivized much of this and to press for corporate decisions which may not be in the long-term best interest of the company or its consumers.

This decade has underscored the devastating impact of political volatility on both the macroeconomic environment and on specific firms. Firms have been ramping up lobbying for years, but it seems the current isolationist climate will place an even bigger premium on their ability to be savvy political operatives and forecasters [1]. This is a fantastic time for firms like Ford to be doubling down on their in-house policy analysis and lobbying efforts to wield stronger influence and better anticipate increasingly impactful political swings to preserve some control over their supply chains.

[1] https://hbr.org/2005/06/managing-risk-in-an-unstable-world

I agree with you Ben that long term Ford should diversify itself away from US, but with a caveat. Ford could focus on procuring raw materials from US suppliers, but move their final assembly elsewhere such as China. By following this model, Ford can continue to support manufacturing jobs in the US, albeit indirectly, while squeezing assembly costs. Furthermore, Ford states that many of their raw materials are single-sourced, which is very risky, so they could turn their attention to finding second sources among suppliers based in US. [1] Therefore to answer your question, “What is better for Americans, more manufacturing jobs in the U.S. or lower cost vehicles?”, I believe it is possible to address both but the jobs would be created by finding and developing second source raw material suppliers.

[1] https://corporate.ford.com/microsites/sustainability-report-2016-17/doc/sr16-annual-report-2016.pdf (Page 13)

Thanks for the great article, Ben. Reading this reminded me of an interesting anecdote on the maquiladora program in Mexico from a company I worked with during my last job. The tax implications for US businesses with maquilas (manufacturing operations that can import and export from Mexico duty/tariff-free) actually go both ways, as Mexico’s 2014 Tax Reform now taxes the operations of certain facilities located in Mexico known as “Shelter Maquiladoras”. Shelter maquiladoras arise when a US company enters into an agreement with an independent contractor in Mexico to essentially find a location and run administrative and HR support for its Mexican manufacturing operations, easing the transition and regulatory hurdles associated with establishing the facility. The below article explains the difference in maquiladora options:

http://www.maquilareference.com/2013/03/options-for-manufacturing-in-mexico/

While the shelter program provided tangible benefits to smaller companies without the capacity to deal with day-to-day operations in Mexico, under the new rules, US companies are now required to establish these shelter maquiladoras as “permanent establishments” for tax purposes, subjecting their Mexican profits to the country’s flat 30% tax. It should be noted that a 2016 tax law now allows a four-year protection period for companies entering into shelter maquiladora contracts before they are required to become permanent establishments. An alternative to the shelter maquiladora would be establishing a directly-owned subsidiary in Mexico, which requires the company go through all of the regulatory and other hurdles but may make more sense given the new tax regime.

Overall, I doubt this applies to Ford, as I am sure a company of its size has directly-owned subsidiaries running its plants, but I believe a number of US companies have taken advantage of this program and figured it may be beneficial to share for those facing decisions regarding whether to locate manufacturing in Mexico in the future. The below article does a pretty good job of explaining the new tax rules and may be of interest. Thanks again.

http://rsmus.com/what-we-do/services/tax/international-tax-planning/mexico-extends-protection-us-companies-shelter-maquiladora-contr.html

Surely, free market agreements are beneficial to all the parties involved. Optimization of resources and labor are critical for an efficient supply chain, and NAFTA surely offers that. However, as these changes with the new administration happen, there are two important thoughts that can put some optimism in this entire situation.

1) In the short term this will most likely hit the cost structure of the automotive industry, thus transferring a representative portion of it to final customers. However, it is important to notice the current trend in minimum wage in Mexico. Since the implementation of NAFTA, minimum wage has gone up by more than 400% (https://tradingeconomics.com/mexico/minimum-wages). Unfortunately to Ford, this trend is continuously going up. Given this move, it is reasonable to think that the competitive advantage in Mexico is likely to fade in a few years. Therefore, in the medium-term this political change in the US will probably not affect the industry that much, since wage costs are likely to converge.

2) There are strategies Ford can implement to avoid disrupting its supply chain. The reality is that the current pressure the automotive industry is suffering from Washington seems to be more of a populist political one. In other words, Ford must give something for the White House to be proud of. With current trends regarding self-driving cars, there is an opportunity for that. Ford could, for instance, invest more heavily in this industry in the United States. This way, the current administration could claim a victory and let the automotive industry continue its operations in Mexico.

Very interesting post – in particular, I think the first question (trade-off between more manufacturing jobs in the US vs. lower cost vehicles) that you posed merits further discussion. In response, think in the short-term, bringing back more manufacturing jobs to the US is important, however, I don’t think it’s a long-term solution given companies’ focus on investing in automation. Additionally, I think having a global footprint for manufacturers is important given different infrastructures and suppliers across regions.

Great article, Ben! As others have mentioned, the questions you pose at the end are fascinating. I generally agree with the sentiments shared above that over the long-term Ford should try to de-risk its supply chain on a global scale (i.e., expand production in China) in the face of NAFTA uncertainties. However, reading through the comments made me wonder about some of the disadvantages with this approach. For one, currency fluctuations between the yen and USD might be hard for Ford to absorb [1]. I also wouldn’t understate the economic welfare implications from lost jobs in the U.S., which we’ve seen play out with auto plant closures in Europe, Canada, and Australia. Regulatory uncertainty abroad should also give Ford pause when considering where to move/build its auto plants. The Chinese government, for example, requires foreign auto-makers to enter into joint ventures with Chinese companies and may introduce regulation that puts pressure on Ford to shift even more towards electric vehicles [2]. Ford would need to weigh these new risks against the risks it would mitigate by moving production outside of NAFTA countries.

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/01/economic-forces-cause-next-auto-industry-gear-change/

[2] http://www.latimes.com/business/autos/la-fi-hy-china-vehicles-20170911-story.html

In the short term I agree that Ford should be pushing politically for the continuation of NAFTA. However, I would further double down on this strategy and argue that Ford, as a major ‘job creator’ in the US, should use their power to draw more public awareness and education on this matter.

With advancements in technology it is clear that the old manufacturing jobs of the Detroit Auto Industry are never coming back. If Ford is to invest in domestic manufacturing, regardless of trade policy, any new factories located in the US will need to be highly automated to be cost competitive and will not have a major impact on job creation (especially not the types of jobs that Trump’s base are looking for). Alternatively, if Ford continues to invest in Mexico or even overseas, if the US withdraws from NAFTA or other new tariffs are put into place, the public will only lose in terms of higher costs for automobiles.

As this change is inevitable, the best thing Ford can do is shorten the amount of time it takes until the public understands the future we are heading towards.

Very interesting and timely issue to tackle. I find it fascinating and telling that when Trump attacked Ford for manufacturing in Mexico, instead of moving the proposed jobs to the US, they moved them to China – yet another low-cost labor location. I think this mindset speaks strongly to the fact that in the long-term, protectionist policies and tariffs ultimately are most detrimental to local consumers – if Ford were forced to locate manufacturing in the US, the prices of Ford Cars would be exponentially higher. If, to promote this domestic production, there were additional tariffs placed on imported cars, the customers would either way face significantly higher prices, and the industry would be driven to a state of reduced competition I think this makes an interesting parallel to recent class discussions we have had about how the government could focus more on worker-retraining in an effort to create jobs, rather than attacking industry in a way that is ultimately value-destructive.

Thank you for a very well-written and interesting article.

The question of “What is better for Americans, more manufacturing jobs in the U.S. or lower cost vehicles” is exactly the right one to ask in my view, as it is one manifestation of the broader philosophical question that this country has been grappling with for several years now. Basic economic theory would suggest that free trade increases aggregate economic welfare. Positive economic effects of free trade include cheaper consumer goods such as cars and electronics. However, the spoils of liberalized trade policy are not spread evenly – and some geographies and industries experience a collective loss of utility as a result of increased foreign competition. We saw this vividly during the 2016 US election, where Donald Trump’s anti-trade rhetoric led to an unexpected swell of support across the “rust belt” states in the upper Midwest where free trade has led to the shuttering of many factories and economic devastation of entire communities.

The government may well decide that a strong domestic manufacturing industry is a national imperative – either for national security or for social welfare reasons. However, in my view such government intervention should have to meet a high standard of evidence and proof of a compelling national interest, as protectionist movements will often reverse aggregate economic gains that have been captured by broad swaths of society.

Great article on an old American company that I personally find very interesting to follow! One item I would like to add to the discussion is the growing importance of Political Action Committees (PACs), given the growing influence of isolationist political movements. From 2008 to 2016, Ford’s PAC spending increased 117% from $805,000 to $1,748,000, while also shifting from 51/49 Democrat/Republic split to 39/61 split in favor of Republicans. Since the company cannot provide funding for the PAC, it must rely on the donations of it’s shareholders and employees. The automotive industry has made a clear effort in the past years to increase fundraising for their PACs. This is because many of the issues you raised in your article. Automotive companies know that they need an established presence in Washington to deal with uncertainties that come from isolationist movements. It allows them to fight for current issues they face, such as currency manipulation, while also keeping a pulse on what an unpredictable government might do next!

Ford PAC spending info:

https://www.opensecrets.org/pacs/lookup2.php?strID=C00046474

Thanks for the article Ben! The increase in protectionist policies and tariffs are not simply an American issue but a global issue at large. Over the last few years there has been a shift in global sentiment to embrace more nationalist agendas. I find it interesting that although these agendas aim to protect local workers they usually come at the expense of local consumers. The key question which remains is “Do the societal benefits of protectionist policies which save local jobs and industries outweigh the negative impact of higher import cost which leads to higher consumer goods?”

Ben, thanks for a clear article on the implications of how the end of NAFTA could affect a very American brand and business. I think this question is really critical especially in light of our case discussion today on Interconnect – as we learned today, there are different considerations for factory operations (the labor laws and cost, worker education, sourcing of raw materials etc) and it is clear that repealing NAFTA will negatively affect what is currently an efficient and reliable operation, resulting in hurting an American company. I especially thought your point about Ford moving their operations to China in order to gain even more savings in their production. The Trump administration will have to think very carefully about the implications of pursuing the end of NAFTA, as businesses ultimately will have to choose the option that will drive efficiency and protect (if not increase) margins.

Regarding the discussion that has been generated by your first question, about whether Americans would be better off with more manufacturing jobs in the US or by facing lower cost cars, I firmly believe that protectionism is not the correct approach to decide.

If we analyze this problem from a macroeconomic perspective, we would realize that the potential jobs to be created in the US markets would be non-sustainable in the long term, due to the absence of a competitive advantage relative to other countries. Sooner or later, foreign manufacturers with such competitive advantages will be able to drive costs lower and market a better product inside the US. The long-term consequences of this process will lead to either having better but more expensive (due to high tariffs) non-US cars leading the US market or closing the US car market for foreign manufacturers, leaving Americans consumers worse off. I think that eventually, same jobs will be reallocated to a different industry, where them can really add value.

Regarding your final question (With the potential for major administration changes in the U.S. every four years, how should companies think about the potential for considerable changes in trade policy on their supply chains?), I think that in the U.S. context at least, we’re in the midst of an aberration Administration and that companies shouldn’t view the wild trade swings of President Trump as a sign that this is the new norm. One might argue that the Democrats could elect a candidate in the mold of Bernie Sanders who would continue the isolationist trade policy, but I think again, that over the course of the next few decades, we will view this period in US political history, particularly as it relates to trade, as a blip in a long march towards greater globalization. Indeed, we’re already starting to see a snap-back by opinion makers in both parties related to the decision to pull out of TPP. They are starting to see how the US abdicated its leadership in trade and that other countries like China, Germany, and Japan are going to pick up the slack, causing the US to lose ground.

And as Sam notes, it’s not as easy to unwind trade deals as POTUS Trump might like to think. While I certainly could be wrong, at least in the US content, I see a reversion to the mean happening on the trade front and if this proves true, companies shouldn’t put undue weight on presidential politics as it relates to their strategy.