Digitalization in the Brazilian Energy Sector: Time for Disruption?

With the forthcoming digital disruption in the Energy Sector, ONS, Brazil's Electric System Operator, faces a critical decision regarding its future operation model.

Fast-paced innovations have been disrupting several industries on the last decades. Despite having changed little in the last century, experts agree that on the next few decades it will be the energy sector’s turn[1]. Companies will have to adapt to the increasingly complex supply chain, as variable and decentralized energy sources will become more relevant. In Brazil, the System Operator can adapt through two different approaches: using technology either to further improve their forecasting systems, or to increase their reaction speed and effectiveness, interacting more frequently with the supply chain.

The Electric System Operator in Brazil

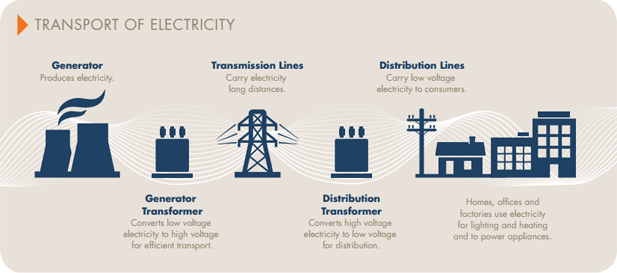

The energy sector is composed of a far-from-ordinary supply chain. In simple language, the product – electricity – is “manufactured” by the generator, flows through the transmitter, and arrives at the distributor, who then sends it to the end-user (residential, commercial or industrial consumer). Bringing in more complexity is the fact that electricity is instantly perishable, meaning the supply-demand balance must be perfectly met at all instants. To guarantee this balance, another role – not present in any other supply chain – comes in: the System Operator.[2]

Figure 1: Electricity Supply Chain[3]

Energy is heavily regulated around the world, thus each country has its own system operator(s) with specific roles. In Brazil, the system operator is ONS – Operador Nacional do Sistema Elétrico (National Electric System Operator), responsible for electricity planning, scheduling, operating, and analyzing, as well as evaluating grid expansion opportunities and integrating new units into it[4]. They are the ones who order power plants to be turned on and off, as well as coordinate the usage of transmission lines.

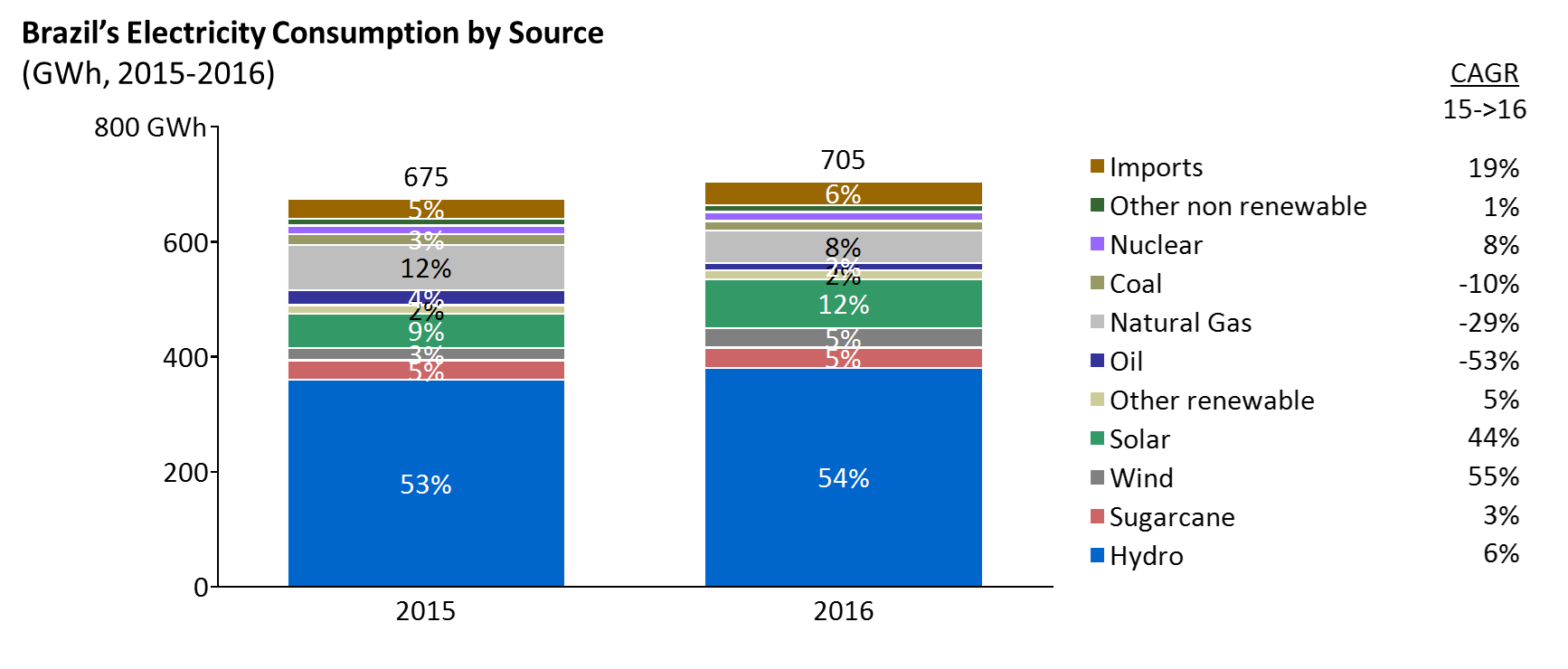

Brazil’s electricity matrix relies mostly on hydropower (61.5% of total generation in 2016[5]), which makes it unique: energy can be stored as water in reservoirs, and generation can be fine-tuned to match consumption by speeding up or down the turbines in hydro plants (thermic plants usually have long startup periods and standard, less flexible energy output). For this reason, ONS’s approach to scheduling (matching supply with demand) has relied heavily on the major role water sources play in Brazil.

Figure 2: Brazil’s Electricity Matrix (% of total consumption in 2015 and 2016)[6]

Digitalization and new Technologies in the Energy Sector

The energy sector is undergoing a series of different trends that might reshape it on the next few decades[7]. With most impact to System Operators are the new generation sources (wind and solar), which will increase daily variability and lack of predictability into levels never seen before. In Brazil, the increasingly relevant wind power not only brings huge variability, but also raises the challenge of aligning several new decentralized plants spread across the territory. Matching supply and demand has never been so complex.

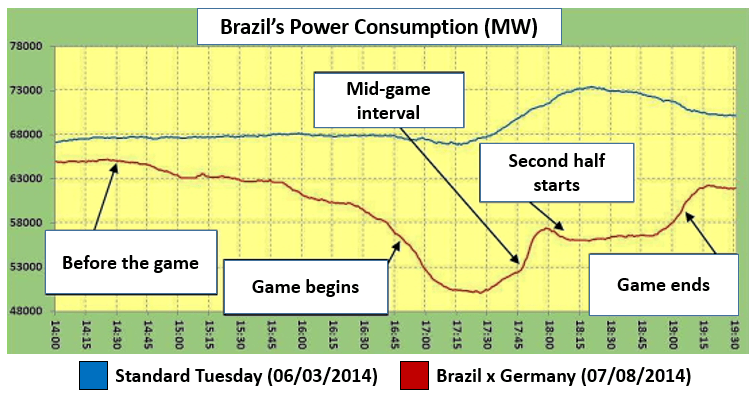

Fortunately, to withstand this complexity, digitalization is also changing ONS’s operation. Smart meters, remote controls, automated systems[8], real-time simulators, and other new technologies have increased their capability to predict, track, and respond to changes. The 2014 World Cup has been a unique opportunity to test great variability on the demand side[9] (during the Brazil-Germany game, energy consumption fell ~30% in a matter of hours[10]), and ONS was able to provide electricity uninterruptedly throughout the Cup. The temporary, short-term challenge was successful. Now, ONS needs to develop supply chain variability management into a long-term, lasting capability.

Figure 3: Comparison of Energy Consumption in Brazil[11]

The future of ONS: which operating model to adopt?

Power generation variability can be managed in different ways. Traditionally, ONS has relied heavily on predicting demand with a 24-hour antecedence[12], matching supply and demand with the flexibility hydro plants provide. With the increased variability, ONS’s prediction systems would have to consider several new factors (for example, wind speed), and more hydropower would have to be saved to offset shifts in wind production – resulting in more oil plants being used, increasing costs and environmental impact.

An alternative approach for ONS would be to use digitalization to better interact with the supply chain, avoiding 24-hour in advance predictions, and scheduling on smaller periods (for example, 6-hour forecasts 4 times a day). This would improve reliability on forecasts, but would require a great shift in both ONS’s and power generators’ operating model. This alternative definitely brings long-term benefits for the Brazilian society, yet needs great alignment and buy-in from the whole supply chain.

Is ONS ready to lead this disruption, or should they play a more passive role and wait for the government and other players to act? More generally, what role should companies play in disrupting highly regulated industries?

(763 words)

[1] O’Brien Browne, “The Disruption And Global Transformation Of The Energy Industry,” Huffington Post, February 27th, 2017, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/the-energy-industry-disruption-and-global-transformation_us_58b428dbe4b0658fc20f97d9, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[2] Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), “National Electricity Market,” https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/ National-Electricity-Market-NEM, accessed November 2017.

[3] Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), “National Electricity Market,” https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/ National-Electricity-Market-NEM, accessed November 2017.

[4] Operador Nacional do Sistema Elétrico (ONS), “Atuação,” http://ons.org.br/pt/paginas/sobre-o-ons/atuacao, accessed November 2017.

[5] Ministério de Minas e Energia (MME), “Resenha Energética Brasileira 2016” (PDF file), downloaded from MME website, http://www.mme.gov.br/documents/10584/3580498/02+-+Resenha+Energ%C3%A9tica+Brasileira+2017+-+ano+ref.+2016+%28PDF%29/13d8d958-de50-4691-96e3-3ccf53f8e1e4?version=1.0, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[6] Ministério de Minas e Energia (MME), “Resenha Energética Brasileira 2016” (PDF file), downloaded from MME website, http://www.mme.gov.br/documents/10584/3580498/02+-+Resenha+Energ%C3%A9tica+Brasileira+2017+-+ano+ref.+2016+%28PDF%29/13d8d958-de50-4691-96e3-3ccf53f8e1e4?version=1.0, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[7] Bain & Company, “Future of Electricity” (PDF file), downloaded from Bain & Company website, http://www.bain.com/Images/WEF_Future_of_Electricity_2017.pdf, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[8] Bain & Company, “Future of Electricity” (PDF file), downloaded from Bain & Company website, http://www.bain.com/Images/WEF_Future_of_Electricity_2017.pdf, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[9] “Brazil Uses EPRI Training Simulator to Ensure High Reliability During World Cup,” T&D World, July 15th, 2014, http://www.tdworld.com/test-monitor-control/brazil-uses-epri-training-simulator-ensure-high-reliability-during-world-cup, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[10] Itaipu Binacional, “Jogo do Brasil na Copa faz Consumo de Energia Elétrica Cair Quase 30%,” https://www.itaipu.gov.py/sala-de-imprensa/noticia/jogo-do-brasil-na-copa-faz-consumo-de-energia-eletrica-cair-quase-30, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[11] Itaipu Binacional, “Jogo do Brasil na Copa faz Consumo de Energia Elétrica Cair Quase 30%,” https://www.itaipu.gov.py/sala-de-imprensa/noticia/jogo-do-brasil-na-copa-faz-consumo-de-energia-eletrica-cair-quase-30, accessed November 13th, 2017.

[12] Operador Nacional do Sistema Elétrico (ONS), “Submódulo 8.1 Dos Procedimentos de Rede” (PDF file), downloaded from ONS website, http://ons.org.br/_layouts/download.aspx?SourceUrl=http://ons.org.br%2F ProcedimentosDeRede%2FM%C3%B3dulo%208%2FSubm%C3%B3dulo%208.1%2FSubm%C3%B3dulo%208.1.pdf, accessed November 13th, 2017.

Interesting article! I think that ONS should take an active role in the transition to a digitalized system. As more types of power sources become prevalent in the Brazilian market and lead to greatly increased variability, it will be extremely important to improve the reliability of forecasts and the efficiency of the entire power system. ONS, and the entire supply chain, will be negatively impacted if such a system is not in place soon. Therefore, they should not wait until this becomes an issue, but rather be proactive in developing and implementing a digitalized system now.

Digitization, as RRE points out, will make a huge impact on the Brazilian energy sector. Although the Brazil energy sector is unique in having 61% of its energy coming from hydropower, which also makes it easier to match power generation to consumption, other utilities across the globe, will have an even harder time adapting to renewable but non-continuous sources of energy like wind and solar.

In addition to the use of smart meters and digital automated systems, energy system operators would be wise to consider advances in battery technology to store energy when there is excess generating capacity. Tesla recently delivered the world’s largest battery to South Australia, to store power from a wind farm, releasing energy in times of increased demand.

It is also very interesting to note the impact of the Brazil-Germany game on power consumption during the 2014 World cup! It goes to show that system operators have to react not just to weather events like a heat wave that drives up energy consumption, but to other events of intense interest to consumers – football in Brazil and perhaps a cricket match in India.

Very interesting read! I think that the ONS has a lot possibilities to improve the energy delivery efficiency, since the Brazilian energy market is still centralized (as compared to most of the mature energy markets).

Here are my thoughts on your two options:

1) Better supply prediction: I think that the prediction cycle should not be too difficult to manage, given that 60% of total energy generation come from hydro sources. As a comparison, Germany generates 25% of its energy demand from renewable energy (wind and solar). There are commercialized and proven programs on the market. For instance, the Wind Power Management System (WPMS), developed by ISET, is used operationally by three of the four German transmission system operators. I think that ONS can definitely benefit from knowledge sharing with countries with higher renewables affinity.

2) Active demand setting: Yes, you are right that household demand is more volatile than before. Given that the residential energy consumption in Brazil only make up to 10% of the total energy demand mix, I would focus on the industrial sector (30% of total energy demand). There, I think that ONS can benefit from more systematic incentive setting. For instance, in DSM (Demand Site Management) programs the energy provider and energy intensive industries (e.g., steel production) can agree on a set demand schedule (1 hour discretization) 24 hours ahead of time. In return for the predictable demand energy intensive industries can enjoy a more advantageous electricity price.