“Digital Refugee”: The Impact of Technology on Syrian Migrants and The Smugglers Who Profit

How is digitization transforming the human smuggling business into Europe? How is it impacting Syrian refugees’ migration patterns and quality of life?

The “Digital Refugee”

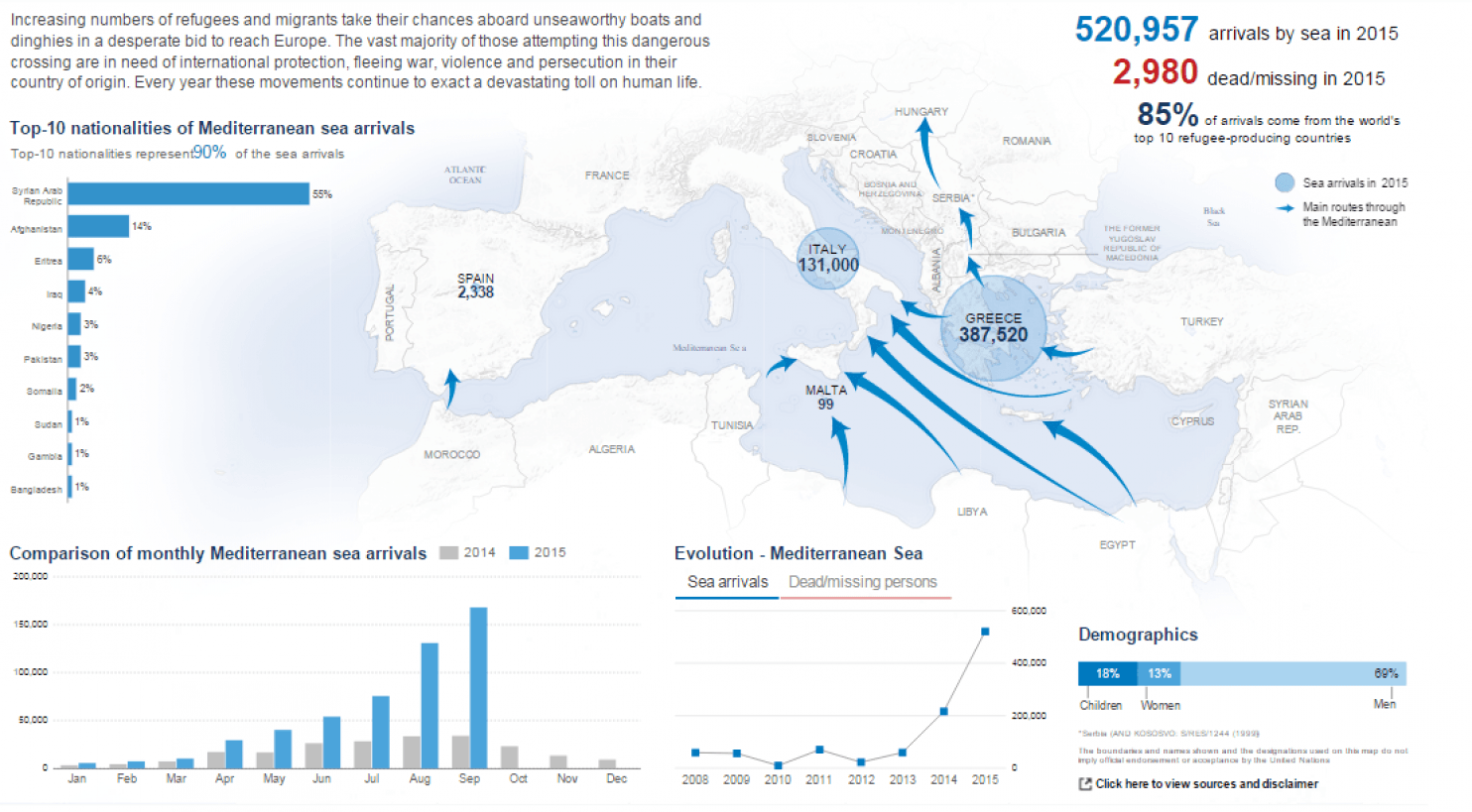

Today, there are over 65 million displaced people–the most since World War II— and nowhere is the refugee crisis direr than Syria [1]. Over half the country’s pre-war population has been forced from their homes; some 5 million have fled the country altogether [2]. Neighbors have absorbed the vast majority: Turkey has close to 3 million Syrians, while one out of every four people in Lebanon is now a Syrian refugee [3] [4]. Yet, international attention focuses disproportionately on the migrant flows to Europe.

The journey to Europe is dangerous, tragic, and unprecedented: it’s the first mass-scale migration to take place in a digital age with virtually ubiquitous smartphone access. For reference, pre-crisis Syria had 87 mobile phones per 100 citizens [5]; one study found that 86% of Syrian youth in a Jordanian refugee camp owned mobile handsets [6]. Mobile computing power transforms reporting—every migrant can tell their story in photos, videos and texts—as well as their prospects for success and even survival. Access to technologies like Google Maps and instant communication apps enables a viable route through Europe, a rescue call to the Coast Guard, or a compass to guide your swimming when a boat sinks [7] [8].

Despite the dangers—3800 people died in the Mediterranean over the first 10 months of this year [9]—insatiable demand for passage has given birth to pragmatic, ever-evolving suppliers. The risks and rewards of digitization shape these smugglers’ strategies.

Human Trafficking Inc.

Human smuggling into Europe has become staggeringly big business. Per Europol, the industry generated between $3 and $6 billion of profit in 2015; 90% of asylum-seeking refugees paid for a criminal enterprise’s services [10]. Overall annual demand for passage to Europe only grows as economic opportunity wanes and violent conflict soars across the Middle East and North Africa.

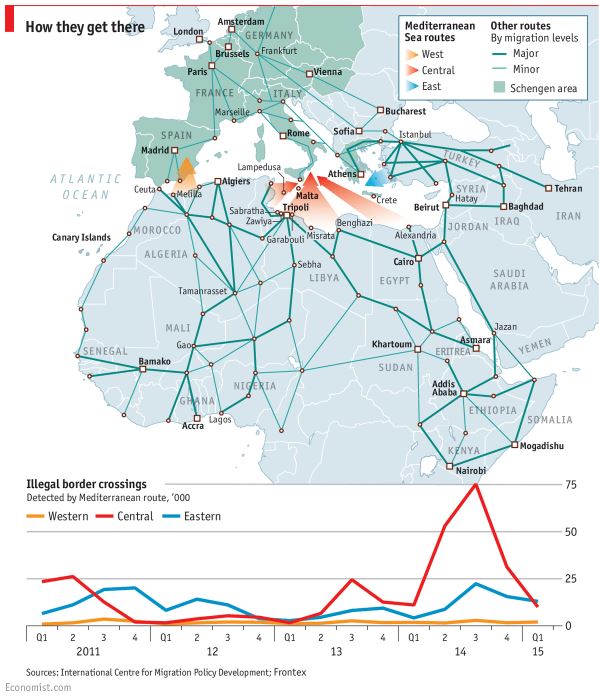

Despite steady demand growth, there is tremendous variability in terms of flow and price. Seasonality is a factor: seafaring routes spike when temperatures are milder (by some accounts, prices can surge 30-50%) [11], [13]. Likely the largest distortionary effect is government intervention. Money spent deterring refugees with walls or border patrols doesn’t seem to make a dent in overall demand—it often just shifts the bottlenecks and reallocates migrant flows to new paths of least resistance that are increasingly clandestine and unsafe [12]. The overhang of illegality drives up costs; for example, in Turkey, smugglers can face prison sentences of 1-30 years and up to $15,000, upping the price that smugglers demand [13]. Even humanitarian triumphs like Germany’s admission of 1 million new refugees can send demand surging [18].

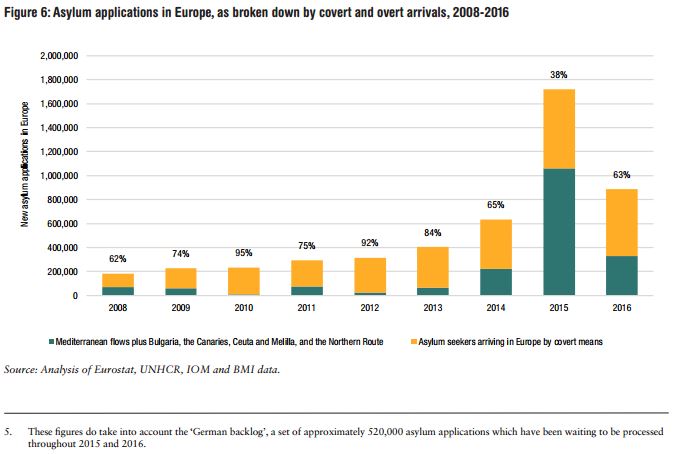

[12]

[14]

[15]

Against this backdrop, what are the biggest operational impacts of digitization?

- Digitization dramatically increases demand variability and complicates forecasting.

Refugees use communications apps like WhatsApp, Viber, Skype and Facebook to communicate in real time; they even share GPS coordinates so others can monitor their paths [17]. This strips out information opacity and lag time in a manner that has a massive network effect on migration routes—the more successful routes tend to exponentially receive more migrants [11]. It can also shorten the lifespans of these paths: governments can leverage this transparency to crack down on the most popular routes or smugglers, triggering the cycle to start from scratch [18]. Smugglers need nimbler, decentralized operations to quickly capitalize on shifting chokepoints and stay one step ahead of government crackdowns.

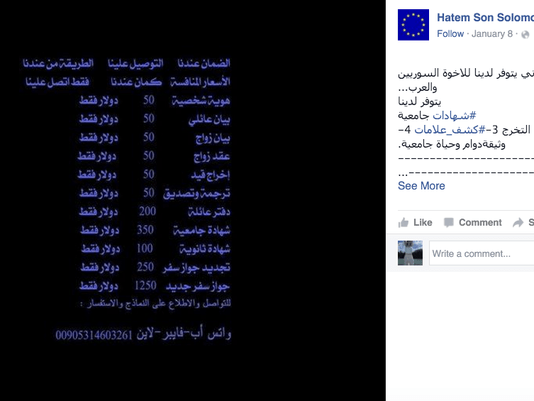

- Digitization opens new channels of demand procurement and helps smugglers go ‘direct to consumer.’

Social media and digitized communications offer smugglers an unprecedented procurement tool: the opportunity to engage in direct marketing, soliciting customers with sophisticated Facebook offerings that can include family discounts, peer reviews, and dynamic pricing [17], [11]. Additionally, smugglers become less reliant on intermediary field agents who publicize smugglers’ services in key geographies in return for a cut [13].

[11]

- On the other hand, digitization leads to smaller jobs and standardized migrant flows that can be less lucrative per customer and require better service.

Migrants’ ability to crowdsource other refugees’ best practices motivates more of them to go it alone and disintermediate the smugglers (at least for segments of the journey that don’t require vehicles) [17]. Says Mohamed Haj Ali of the Adventist Development and Relief Agency in Belgrade: “Traffickers are losing business because people are going alone, thanks to Facebook” [17]. Refugees can quickly vet smugglers’ offers based on denser feedback; this quality control and price visibility pressures smugglers’ profitability.

***

Digitization clearly reduces the information gaps upon which smugglers can thrive. But in such a complex system, it’s hard to determine whether digitization is net positive for refugees, smugglers, both or neither. The cause-effect is not straightforward; for example, pricing pressure on smugglers can incentivize them to use cheaper, life-threatening boats [18].

Yet, the central truth is simple and tragic: demand isn’t drying up. As long as turmoil rages across MENA, people will flee their homes and risk everything in hopes of a better future.

(TOTAL WORDS: 796)

Sources

(Note: For the sake of brevity, this post’s statistics and terminology shift between referring to Syrian migrants and the overall refugee flows to Europe, of which Syrians make up just one part. This is largely to capitalize on the best sourcing, which can come from either bucket).

[1] The UN Refugee Agency, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/latest/2016/6/5763b65a4/global-forced-displacement-hits-record-high.html, accessed Nov 2016

[2] Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, http://internal-displacement.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/syria/figures-analysis, accessed Nov 2016

[3] Ishaan Tharoor, “Turkey’s Bold New Plan For Syrian Refugees: Make Them Citizens,” Washington Post, July 2016 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/07/09/turkeys-bold-new-plan-for-syrian-refugees-make-them-citizens/, accessed Nov 2016

[4] Oxfam International, https://www.oxfam.org/en/emergencies/refugee-and-migrant-crisis, accessed Nov 2016

[5] CIA World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sy.html, accessed Nov 2016

[6] Penn State College of Information Sciences and Technology Report, March 2015, http://news.psu.edu/story/350156/2015/03/26/research/ist-researchers-explore-technology-use-syrian-refugee-camp, accessed Nov 2016

[7] BBC News Video via YouTube, “Migrant crisis: ‘We would be lost without Google maps’ – BBC News”, Sept 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zcr-GWv3Qbs, viewed Nov 2016

[8] The World Bank blog, “4 smartphone tools Syrian refugees use to arrive in Europe safely,” Feb 2016, http://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/4-smartphone-tools-Syrian-refugees-use-to-arrive-in-Europe-safely

[9] UN Refugee Agency Spokesperson William Spindler, as reported in France24, http://www.france24.com/en/20161026-mediterranean-sea-migrant-deaths-2016-record-refugees, accessed Nov 2016

[10] Head of Europol Rob Wainwright in The Independent, Jan 2016, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/refugee-crisis-human-traffickers-netted-up-to-4bn-last-year-a6816861.html, accessed Nov 2016

[11] Shira Rubin, “Daring human smugglers use social media to lure migrants fleeing Syria,” USA Today, Jan 2016, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2016/01/26/migrants-smugglers-social-media-syria-turkey-greece-facebook/79347784/, accessed Nov 2016

[12] Overseas Development Institute Report, “Europe’s Refugees and Migrants: Hidden Flows, Tightened Borders, and Spiralling Costs“, Sep 2016, https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10887.pdf, accessed Nov 2016

[13] Yasser Allawi, “A Syrian Smuggler Working On Turkey’s Shores Speaks Out,” Huffington Post, Mar 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/syria-deeply-interview-people-smuggler-turkey-greece_us_56facd51e4b0143a9b497365, Nov 2016

[14] Janell Ross, “Suspicions of Syrian Refugees Coming to the U.S.? Here’s a Reality Check,” Washington Post, Oct 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/10/02/donald-trump-has-his-suspicions-about-syrian-refugees-they-are-unfounded-heres-why/, accessed Nov 2016

[15] The Economist, “Europe’s Boat People,” May 2015, http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2015/05/graphics, accessed Nov 2016

[16] Alessandra Ram, “Smartphones Bring Solace and Aid to Desperate Refugees,” Wired, Dec 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/12/smartphone-syrian-refugee-crisis/

[17] Matthew Brunwasser, “A 21st-Century Migrant’s Essentials: Food, Shelter, Smartphone,” New York Times, Aug 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/26/world/europe/a-21st-century-migrants-checklist-water-shelter-smartphone.html?_r=0

[18] Jillian Melchior, “Who Benefits from Syria’s Refugee Crisis: Human Smugglers,” National Review, Oct 2015, http://www.nationalreview.com/article/426046/human-smugglers-profit-syrian-refugee-crisis

Further Reading on technology-based private sector / NGO contributions to improve refugee quality of life

–“The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has distributed 33,000 SIM cards to Syrian refugees in Jordan and 85,704 solar lanterns that can also be used to charge cellphones.

“For the U.N.H.C.R., there is a shift in understanding of what assistance provision actually is,” said Christopher Earney of the refugee agency’s innovation office in Geneva.”

Source [17]

—‘Despite the dire conditions that many Syrians are facing, Maitland said that upon arriving at the Zaatari camp in Jordan, the researchers discovered a vibrant and resilient community. Children in the camp are formally educated and able to receive a Jordanian high school diploma. In addition, about 3,000 businesses have been set up in the camp, including barber shops, wedding gown rentals, vegetable stalls and even a travel agency and pizza delivery service. Use of information technology by the humanitarian organizations is expanding rapidly, including biometrics, electronic vouchers, and social media. UNHCR maintains a database of iris scans of all refugees, who purchase food using UN-issued debit cards containing their monthly food allowance at point-of-sale terminals at two grocery stores in the camp. UNHCR also operates a Twitter account for the camp, providing updates and human interest stories. Following the camp’s Twitter feed has allowed the research team to keep up with timely news, including the past winter’s snow storms.’

Source [6]

–“Information access has to be in every humanitarian toolkit

in the future, so we’re not struggling to provide basic things like Internet access and charging stations” — Kate Coyer, director of the Civil Society and Technology Project for the Center for Media, Data and Society at Central European University in Budapest.

http://mashable.com/2015/11/08/refugees-technology-aid/#5d7LoCvTZkqo

Lists/Examples of the Private Sector Making an Impact:

http://www.justmeans.com/blogs/private-sector-takes-steps-to-address-the-global-refugee-crisis

https://www.wired.com/2015/12/smartphone-syrian-refugee-crisis/

http://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/how-the-technology-industry-is-helping-refugees/3574767.html

http://www.dw.com/en/how-technology-can-change-the-refugee-crisis/a-19295937

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/10/google-crisis-info-hub-refugees-151024061606185.html

https://www.wired.com/2016/01/google-donates-millions-to-help-refugees-get-online/

Thank you for such a compelling reminder about the enormous risks migrants are willing to take to escape heart-breaking conditions. I hadn’t considered the role of digitization in the MENA refugee crisis, but it makes a lot of sense – the ability for people to share information easily a la social media / direct messaging platforms *because of* cheap mobile phones means that the asymmetric information gap between smugglers and refugees is dramatically reduced.

One thing I am curious about is mobile money transfers, and how transfer patters patterns relate to refugee movement. In particular, people in developing countries (especially in Africa, Asia and the Middle East) with limited physical bank access tend to use their phones to transfer money. As smugglers become pushed out of the migrant movement process, do they perhaps enter the migration cycle through mediating money transfers, or with helping set up and transition migrants into their new country?

Perhaps most tragic, of course, is that the conflict forcing Syrians from their country isn’t abating anytime soon. Does this means that specific technological solutions will need to be built in order to better facilitate safe movement across borders? Or are existing communication platforms sufficient?

Thank you for this excellent on piece on the impact of digital technologies on the Syrian refugee crisis. Indeed technology is dramatically changing the balance of power between smugglers and refugees, who now have unprecedented access to information and the ability to communicate with families and friends.

Another interesting impact of technology is on the humanitarian sector, which is now heavily leveraging technology to enhance its impact across Europe.

Refugee.info, for instance, is an excellent platform for refugees to find all information regarding border crossing, asylum options and emergency contacts.

Trace the face is an initiative by the Red Cross to help migrants find relatives and friends that they have lost during the journey [2].

Many efforts are also made at a city level: Dresden, for instance, has launched a dedicated app, Welcome to Dresden, to help incoming refugees find healthcare, register with the authorities and integrate [3].

Amid all this sufferance and political inaction, it is heartening to see that people are still showing compassion and solidarity, and that technology is helping them to be more effective at it.

[1] http://www.refugee.info/

[2] https://familylinks.icrc.org/europe/en/Pages/Home.aspx.

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/17/smartphone-app-launched-help-asylum-seekers-dresden-germany

LinkedIn Europe is trying to make a platform that allows Syrian refugees living in developed areas in Europe to connect w employers and incentivizes employers from engaging with this highly active, smart population. Simply connected talent with potential employers is a huge gap in what makes assimilation to a new place difficult for this massive population and to create tools to specifically encourage and enable this with proper language, etc. is wonderful.

Thank you for writing about such a relevant yet under-reported topic. It is interesting, though not entirely surprising, that governments have been unable to stem the flow of immigrants and that digital technology has been one of the main causes of that. What is surprising to me though is the fact that government action has in fact put more immigrant lives in danger by forcing them to take more dangerous routes. It means not only are government agencies unsuccessful in deterring the flow of immigrants, they are endangering immigrants by forcing them to take greater risks.

It was encouraging to read about the greater access to information refugees are now receiving. As the State Department discusses in its 2016 human trafficking report, we have seen a rise in the number of trafficking cases related to Syria as the civil war has escalated. It is great to see that refugees are now able to get information on the people they are paying beforehand. To take it a step further, I wonder if something could be done to further combat trafficking, given how globally ubiquitous technology has become.

Quinn, agreed that it is great that refugees have greater access to information before they agree to pay a smuggler. I also wonder to what extent some platforms can create specific tools to aid refugees in this information sharing. It seems like they are mostly using traditional social media. That said, I would think someone like Facebook could optimize a “quick and dirty” application to aid refugees in their time of need. This could be an interesting way to help in the cause, as well as receive some great accolades and positive PR from the press back home.

Thanks MS for this well-documented article on an unexpected impact of digitalization.

Despite potential negative impacts, I’m convinced that mobiles greatly helped raised awareness about migrants among western population, thanks to videos, live reporting and pictures. But this is of course not enough to solve this humanitarian disaster.