“Delivering Happiness” – Serving Customers Without a Storefront

Digitalization of food delivery through the emergence of food-delivery platforms enables small business owners to operate without a physical store. As the popularity of these services continue to grow, how should restaurants adapt to stay competitive?

It’s another busy morning for Fikri Gustin; he hasn’t had a slow one since starting up Martabak Monkey – a pancake restaurant based in Bandung, Indonesia two years ago.[1] There is something very unusual about his restaurant: it has no tables, chairs, menus, or storefront. In fact, the only thing that resembles a restaurant is his small kitchen with two gas stoves. Operating straight from home, green-jacketed ‘riders’ line up in Fikri’s living room, waiting for their customers’ orders to be packaged.

Digitalization of the Food Delivery Industry

With the introduction of GO-FOOD, an app-based food-delivery platform in Indonesia, Fikri is able to fulfill his dream of opening a restaurant out of his kitchen. Indeed, this technology has enabled small business owners like Fikri to operate a restaurant without having to open a physical store at all, adopting a fully digital delivery model where orders are automatically relayed from the customer to the restaurant in real-time and freelance riders are automatically assigned based on proximity to fulfill orders. This dramatically reduces initial capital requirements and subsequent operational costs of a restaurant business.

The Rise of GO-JEK

GO-FOOD is a food-delivery service offered through the GO-JEK app ecosystem, Indonesia’s first tech unicorn currently valued at ~US$3 Billion.[2] Started from its humble beginning as a ride-hailing app for bikes, GO-JEK rapidly expanded to provide a wide variety of services such as at-home massage and housekeeping. GO-JEK Co-Founder and CEO Nadiem Makarim (HBS ‘11) described the company as a “platform for the on-demand economy”.[2] As this trend continues throughout Asia, pressure mounts for restaurant-owners to partner with these providers in order to remain competitive. In China for example, it is predicted that as many as 350 million consumers would have used similar services in 2018.[3]

GO-JEK riders waiting to pick-up GO-FOOD orders at a food store in Jakarta.

Source: Reuters [4]

Good for Consumers, Bad for Merchants?

Fikri and many other forward-thinking entrepreneurs decided to ride the wave of change by becoming one of the first merchants to partner with GO-FOOD in 2015. Since then, GO-FOOD’s restaurant partnerships has grown from 15,000 at launch to more than 85,000 in 2017.[5] Fikri himself has seen 100-fold increase in the orders he received.[6] Research done by other organizations support this evidence: Indonesia Franchise Association estimates 30% increase in revenue of its members after partnering with the platform.[4] In the short-term, many more restaurant owners will follow Fikri’s steps in partnering with GO-FOOD to gain access to the growing massive customer base.

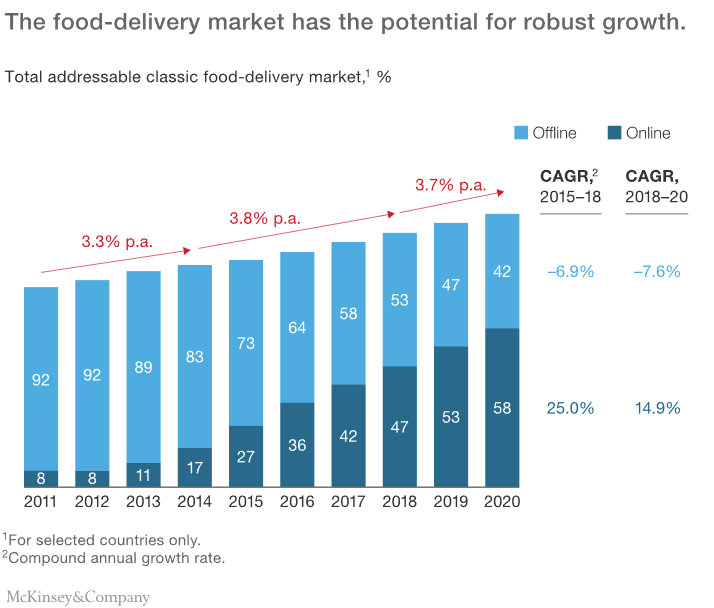

Source: McKinsey and Company [7]

The medium-term paints a different picture. As many more restaurants and big franchises form partnership with GO-FOOD, relative competitive advantage of each partner diminishes, as every player would gain access to both the customer-base and rider-base. Furthermore, the visibility advantage also diminishes since the customer will be flooded with a wealth of choice. To this point, Fikri’s medium-term strategy is to eventually build his own delivery armada.[8] He predicts that this is only possible if his brand has grown popular enough such that customers is willing to contact him directly. At that point, paying salary to deliverymen may become cheaper than the 20% cut GO-FOOD charges per transaction.[9]

Recommendations

Martabak Monkey should prepare both offline and online advertising campaigns to increase customers’ awareness. This allows them to increase orders in the face of growing competition with other restaurants featured on GO-FOOD. Martabak Monkey could employ a unique yet cost-efficient marketing strategy using social media, online influencers and paid advertising campaigns. They could also analyze customer behavior data available through the GO-FOOD platform to enable them to optimize inventory and labor usage with regards to predictable movements in demand.

In the medium-term, Martabak Monkey should prepare for upstream digitalization. GO-JEK or other companies might provide similar platform specializing in ingredients and inventory procurement, with wholesalers and grocers as partners. This could potentially revolutionize the sourcing industry by enabling restaurants to closely manage their inventory and perform JIT ingredients delivery through riders. Again, Martabak Monkey need to maintain its position as early adopter to keep an edge over the ever-growing competition in the food services industry.

Conclusion

The digitalization of food delivery serves as an example that a third-party may add value to the supply chain by bridging the gap between existing restaurant-customer relationship. By increasing visibility of supply and demand, and reducing the lag time in order fulfillment, platforms such as GO-FOOD eliminates the need for a physical storefront and traditional delivery system. However, as the number of restaurant partners grow, the visibility benefits brought by the platform diminishes, as customers is faced with increasingly complex variety of options.

As Fikri expands his franchise to five cities this year, what should he keep in mind regarding his increasing dependency on GO-FOOD? What would happen to his business if a GO-FOOD competitor enters the market?

(Word Count: 796)

References:

[1] GO-JEK Indonesia, “GO-FOOD Merchant Story – Martabak Monkey (Bandung),” YouTube, published June 23, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Li_LY9nmaUw, accessed November 2017.

[2] Sudhir T. Vadaketh, “June Cover Story: The Go-Jek Effect,” Inc. Southeast Asia, May 29, 2017, http://inc-asean.com/editor-picks/GO-JEK-effect/, accessed November 2017.

[3] Wang Zhuoqiong, “Delivery apps gulp down food biz,” China Daily, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2017-11/06/content_34172385.htm, accessed November 2017.

[4] Gayatri Suroyo and Stefanno Reinard, “Jakarta’s traffic-clogged economy gets a lift from motorbike deliveries,” Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-economy-gojek/jakartas-traffic-clogged-economy-gets-a-lift-from-motorbike-deliveries-idUSKBN1AA2W5, accessed November 2017.

[5] Antonia Timmerman, “Go-Jek’s food delivery beats all Indian food startups combined: Piotr Jakubowski,” Deal Street Asia, https://www.dealstreetasia.com/stories/after-foodpanda-GO-JEKs-food-delivery-beats-all-indian-food-startups-combined-piotr-jakubowski-cmo-69821/, accessed November 2017.

[6] Fikri P. Gustin, “Do Not Pray for Easy Life, Pray to be Stronger Man,” Medium, April 6, 2017, https://medium.com/@sippii/do-not-pray-for-easy-life-pray-to-be-stronger-man-2b3adea4bd6e, accessed November 2017.

[7] Carsten Hirschberg et al., “The Changing Market for Food Delivery,” McKinsey & Company, November 2016, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/high-tech/our-insights/the-changing-market-for-food-delivery, accessed November 2017.

[8] Fikri P. Gustin, “Pros and Cons of a GO-FOOD Partner,” Kaskus, April 19, 2017, https://www.kaskus.co.id/post/58f78be112e25794438b456e#post58f78be112e25794438b456e, accessed November 2017.

[9] Wataru Suzuki, “Indonesia ride-hailing app finds new opportunities in food delivery,” Nikkei Asian Review, August 21, 2017, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Companies/Indonesia-ride-hailing-app-finds-new-opportunities-in-food-delivery, accessed November 2017.

This raises an interesting potential outcome of vendors on the GO-FOOD platform – that they may build a brand for themselves and eventually leave the platform by building out a physical storefront and/or own delivery system. Although this results in lost business for GO-FOOD, it also shows the positive externalities of a digital platform like GO-FOOD in empowering more entrepreneurs by lowering the barriers of entry to the restaurant business. However, I believe most vendors are unlikely to gain the brand recognition or demand required to build out their own delivery infrastructure, given that customers who use the GO-FOOD platform probably value choice (being able to have different cuisines every time) and convenience (only dealing with one app instead of multiple). Even if they do decide it is worth having their own delivery infrastructure, Martabak Monkey should not leave the platform entirely, as it is still a cost-efficient marketing strategy and a good way to generate demand outside of the loyal customer base.

Nicholas, I really enjoyed this post. Great description of an innovative business model taking advantage of new, digital opportunities. Your last question raises a good point about what Fikri should do moving forward, given that he doesn’t own this section of his supply chain, the digital delivery, and therefore it’s not an ownable differentiator for him. I do think Fikri would likely benefit from a G0-FOOD competitor or competitors entering this market, as competition might drive prices/commissions down for food suppliers like him and would keep pressure on GO-FOOD and all competitors in the market to keep the delivery operation as efficient as possible, lowering costs for suppliers, customers, or ideally both. Your suggestion that Fikri will end up building his own delivery service is very interesting – GO-FOOD reminds me of Li & Fung aggregating and servicing demand for small companies, but maybe that doesn’t make as much sense once you get to scale and therefore he should build his own force. If he does build his own delivery force, maybe he could try to use customer data to optimize how many drivers he hires per hour, by day, and time of the year. Potentially, if GO-FOOD’s cut is too expensive, maybe he should think about building another free lance force by partnering with other local businesses on a small scale to pool their demand for a lower commission (which would attract more food-suppliers, given the lower fees, and could attract riders, even at the lower commission, if there is currently more supply than demand for free-lance riders). It would be difficult and expensive to compete head to head with GO-FOOD’s matching algorithm and application software most likely, but on a small scale, potentially a simple interface without an advanced algorithm could provide some demand aggregation benefits for a few local businesses at a lower cost than a dedicated sales force. In addition to incorporating up-stream digitalization as it happens (as you point out), I wonder if Fikri could incorporate these digital optimization concepts further into his business model, potentially by using historical customer order data to plan out his labor allocation and maybe proactively manage his raw material inventory. If he isn’t already, he could also use the digital platform to try to get additional visibility into customer behavior, e.g., by allowing advance ordering. Maybe, if he’s really successful and feeling adventurous, he could also pilot a mini-drone program. That might be a marketing campaign in itself!

This is a clear example of how technologies are disrupting businesses in the developing world, where micro entrepreneurship will be vital to the well-being of the population. In this case, GO-FOOD diminishes the capex investment necessary to install a supply chain in the food retail industry in Indonesia. With less initial capital, supply chain gets leaner, thus facilitating entrepreneurship.

However, it is important to put every endeavor in context, especially in the developing world. In Indonesia, in order to impact the entire country, it is necessary to understand the complex geography of the region. If this technology is aiming to disrupt and touch many other businesses and lives, it will have to develop a way to facilitate the supply chain among the many Indonesian islands. This would be very important to the equal development of such an unequal country. I am curious to see what the future holds for this adventure.

I think the first question that you are posing is extremely relevant for this business. Many restaurants that operate in the “traditional” way are now using food-delivery platforms to satisfy their customers’ needs, and potentially increasing their sales. However, Martabak Monkey business is designed to fulfill only the food-delivery business, therefore it is, highly dependent on the platform. The suggested marketing strategy would be helpful to increase awareness and promote consumption of their products. However, how can the company remain relevant if the platform grows and increases the number of restaurants available to customers? As you mentioned in your post, the company would benefit from having their own delivery fulfillment program to overcome this issue. Additionally, the digitalization of their business would also allow them to improve the procurement and logistics decisions.

By launching their own delivery platform, Martabak Monkey would have a new challenge: to convince customers to use their own platform instead of Go-Food or any other that offers a wider range of options. From what we’ve learned in the past weeks, my recommendation would be to attract and retain customers by implementing two actions. The first one would be to develop a loyalty program to encourage customers to place their orders through Martabak Monkey delivery platform, by offering rewards such as discounts, or free meals to recurring customers. The second one would be to offer a better delivery service (easier, customizable, faster) to customers, so that they think of the company’s platform as their first choice to order food.

I really enjoyed reading this article. It’s great to see this type of innovation take hold in the emerging SE Asia markets. While this creates opportunities for new jobs in the F&B scene, I am concerned about what role GO-FOOD has on ensuring food quality and safety. GO-FOOD should be accountable for quality and safety and consider what standards and controls they will implement as they sign on new suppliers.