Alibaba Has Something to Say about What You Should Buy and Whom You Should Marry

Its highly personalized app seems to know you better than you know yourself. But is there such a thing as too much personalization?

The impressive scorecard

Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant, reported a whopping $30.8 billion[1] in gross merchandise volume (GMV) on its online marketplace during the 2018 “Singles Day” – a 24-hour shopping festival. This new record represents a 27% growth year over year, more than doubling total combined sales on Cyber Monday, Black Friday and Thanksgiving Day in the US in 2017[2].

The beginning of personalization

To sustain and fuel such growth, Alibaba has in recent years invested heavily in machine learning technologies to better equip its e-commerce ecosystem participants – consumers, merchants, payment processors and logistics partners. Some important applications include AI chatbots with real-time translation capability, automated marketing content creation tools, and advanced demand forecasting system to help brands plan “from-idea-to-shelf”[3].

Arguably the most impactful use of machine learning at Alibaba is the highly personalized Taobao app (its flagship China e-commerce app), a product feature nicknamed 千人千面, or “A Thousand People, A Thousand Faces.” In a nutshell, the backend engine is constantly taking in a myriad of user attributes as inputs, running its proprietary algorithm, and creating a unique and ever-improving app interface for each user. In fact, 千人千面 has become one of Alibaba’s definitive strategies to-date. As users increasingly moved to mobile from desktop (now over 90% transactions happen on the mobile app[4]), 千人千面 solved the critical issue of adapting content from the desktop browser to a much smaller phone screen with more fragmented user traffic.

The results, reported and unreported

To be clear, this is not your everyday app personalization. Alibaba’s almost obsessive data-driven optimization, aided by its expansive reach of user data (the company has full or partial ownership of the leading Chinese apps in ride sharing, mobile payments, food delivery, video browsing, and microblogging), has brought personalization to a whole new level. Since the introduction of 千人千面, app usage and conversion metrics have improved dramatically. Average app-browsing time climbed to an astonishing 45 minutes per user per day[5].

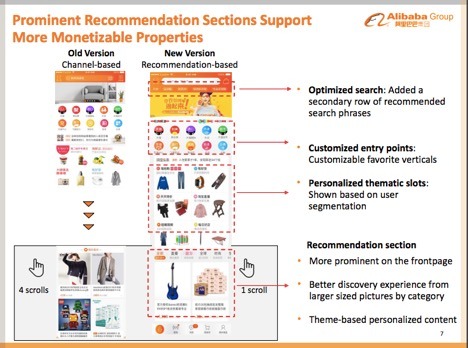

Indeed, increased efficiency is the key objective of 千人千面. Each square-inch space on the mobile app has become a “monetizable property,” its content carefully curated to ensure high click-through and probability of eventual purchases.

Exhibit 1: Management offered insights on Taobao app homepage design[6]

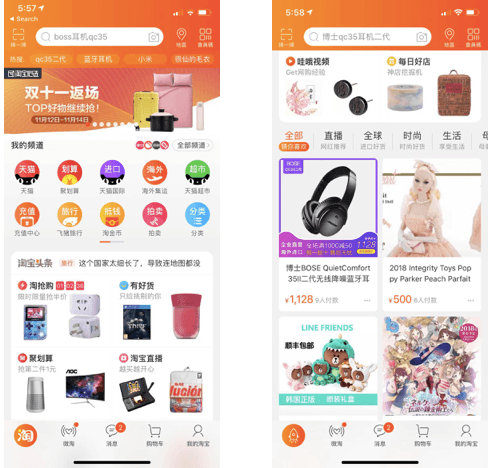

Exhibit 2: Personalized Taobao app homepage

User A: 28-year-old female, active lifestyle, likes food and skincare

User B: 24-year-old female, likes electronics and gaming

Now here is the much overlooked problem. Alibaba knows the user so intimately, that its personalized app is helping users discover brands and products they don’t even know they will like. Oftentimes, users do end up liking these products and become the exact users they were predicted to be. This self-fulfilling effect is even more prominent when the app is the dominant market player, counting 666 million mobile active users in 2018, or 48% of the entire Chinese population[6]. Over time, the yoga-loving woman in her late twenties develops the same taste in snacks as millions of others, while the urban middle-aged man showing a desire for high quality of life (e.g., buys Egyptian cotton bedsheets) becomes an aspiring cyclist with an expensive bike and professional gear – just like all of his male colleagues.

This user convergence and the resulting homogeneity are profoundly alarming. Some top-grossing products emerging in recent years seem just so random: mixed nuts from Costco, “liver detox” supplements from Swisse (a 2nd tier brand in its home market Australia), and 100% cotton wipes from a domestic startup brand. These are likely all high-quality products, but they wouldn’t have reached bestseller status in the absence of the extreme adoption of 千人千面.

The Taobao app’s high efficiency has come at a cost of brand and product diversity. In generating ever-improving conversion metrics, these algorithms pose a severe challenge to the democracy and neutrality of content on Alibaba’s marketplace. Management is aware of the problem, but internal debate continues on whether it should modify this “ruthless” personalization mechanism to give way to more free browsing and advertising.

Recommendations

I believe Alibaba should scale back on the use of 千人千面. In the very least, it can refine the attribute weighting system (e.g., adjust down the weight on previous purchases and searches, and up that on tags like “laid-back” or “liberal”), and designate more app space to algorithm-light content. This may hurt Alibaba’s short-term performances, but will boost its long-term prospects by expanding the universe of products and consumer use cases. As a company with such significant reach and market power, Alibaba should reflect on its social responsibility and closely evaluate the impact brought by its adoption of new technology.

Clearly, the advanced personalization dramatically improves user experience, at least initially. I wonder, is it possible that the algorithm does truly know us better than we know ourselves? Further, is it more patronizing for Alibaba to offer a fully personalized app experience, or to attempt to police the content democracy?

Word count: 793

[1] TechCrunch, “Alibaba sets new Singles’ Day record with $31B in sales, but growth is slowing”. https://techcrunch.com/2018/11/11/alibaba-singles-day-2018-31b/, accessed Nov 2018

[2] Quartz, “Forget Black Friday, Singles Day is the world’s biggest shopping event.”

https://qz.com/1458107/forget-black-friday-singles-day-is-the-worlds-biggest-shopping-event/, accessed Nov 2018

[3] [4] [5] Form 20-F, Alibaba Group Holdings Ltd, filed on July 27, 2018. https://otp.investis.com/clients/us/alibaba/SEC/sec-outline.aspx?FilingId=12879202&Cik=0001577552&PaperOnly=0&HasOriginal=1, accessed Nov 2018

[6] 2Q FY2019 Quarterly Results Presentation, https://www.alibabagroup.com/en/ir/presentations/pre181102.pdf, accessed Nov 2018

I must applaud the engine’s sense of fashion, since it’s recommendations of Taobao fashion shops to me are pretty much on target. On a more serious note, the algorithm may have captured the holy grail of all marketing professionals: How to make consumer buy the product. The recommendation system is self-reinforcing because the users liked what Alibaba recommended them and went ahead with the purchase. While the omniscience of the engine may appear disturbing, in all likelihood it is also a mirror that reflects consumer tastes and preferences back to us.

More interestingly, this system seems to produce winners with no clear merits over their competitors’ offerings, as you have pointed out in the essay. I wonder if this is because the algorithm amplies small differentials in preferences by pushing recommendations to more people?

I’m not sure I agree that the convergence of product preferences is detrimental to Alibaba. Doesn’t it let them funnel customers to the products that make it the most money? And even if it is detrimental, rather than abandon the personalization, can’t they simply tweak it to incorporate more variability? I agree that Alibaba has a huge amount of influence over what consumers purchase, but perhaps that’s not such a bad thing.

Fantastic and eye-opening article!

I agree with your notion of the app’s suggestions becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Especially in fashion and other consumer trends, the masses have proven to be terrible at predicting what becomes the next big thing. Instead, we are all influenced and prompted by media and the people around us. Alibaba is taking over that role by exposing us deliberately to very specific things – thereby adjusting our future tastes. So even though right now I believe we still know ourselves better than Alibaba does, we are at risk to slowly grow into the human beings Alibaba has predicted us to become.

Very well-done article. I really enjoyed reading your take.

I don’t think that Alibaba’s ability to recommend personalized experiences means that the company knows us better than we do ourselves. However, you raised an interesting point that the products Alibaba recommends can, over time, actually shape types of products we buy and the people we become (e.g., the cycling example you gave).

This is still concerning to me. It’s easy to not realize how personalized an in-app experience is and to assume the products we see everywhere are simply popular among everyone. Clearly, given their use of targeting, this is not actually the case.

I wish I knew Chinese now to be able to use Taobao ! Thank you for this great article.

More seriously, I share your concern about the power of Alibaba (and I share similar concerns regarding of the GAFA). These companies can now decide which brands to promote, when and to whom without being controlled by any regulations.

I however do not believe these algorithm know us better than we know ourselves. On the contrary, we are seing and increasing trend of people turning away from these big companies because we realize the power that they and the value of the ‘free’ data we offer them. I believe government should step up to control these companies worldwide to limit the power they have.

I do not share your concerns over the highly personalized nature of Alibaba’s services. What if we are truly destined to have similar tastes in snacks or to use Egyptian cotton bed-sheets! Jokes aside – I see personalization through machine learning as an efficient marketplace for allocation of our resources (time, money) to those areas where we perceive greatest value (e.g. willingness to pay). Where this really gets interesting is if that allocation is not truly efficient (e.g. the marketplace is pushing us to allocate capital in ways that do not satisfy our true interests in allocating capital). This seems to be an implicit assumption of your analysis but you never truly make the link as to why this is a bad thing. I would be interested to hear your thoughts on why app that distribute content should be designed as ‘content democracies’. This was an interesting read!

Although I do see your concern related to Alibaba’s market power and the potential impact they have on consumer choice, I personally believe what Alibaba does actually significantly increases consumer’s utility. The middle age man buying cycling gear will for instance not have to spend hours searching for the right new cycling gear, he will see relevant ads when he is browsing the app and can chose for himself whether it is something he wants to buy or not. I believe the only real alternative is for the same user to be shown a large number of ads that are not targeted to the user, leading to a high number of ads that will be viewed as interruptive to the user.

I do agree that we should proceed with caution with the tech titans that have become so dominant at an unprecedented pace, but as long as personal information is kept safe from cyber criminals, are collected willingly by an informed consumer and are used in places where the consumer clearly views them as ads, artificial intelligence in personalisation is in my eyes simply an improved version of advertising that leads to higher consumer utility. It is then up to regulators to ensure that no one player in the economy gets too much market power or misuses the personalised information by mislabelling ads, steal information from consumers or sell/lose user information against user’s will.

This is a very thought-provoking article!

Given many of Alibaba’s recommendations are based on past purchases from individuals of a specific profile, I often wonder whether these algorithms are actually stifling evolutionary behavior and product adoption…if past behavior is always fueling future behavior, do individuals have a fair opportunity to find new products? What incentive do product development teams to create a drastically new product if its unique characteristics will actually prevent it from being purchased?

Regarding your question of whether computers actually know us better than ourselves, I think the answer is no. I would argue that these computers aren’t so much identifying our existing preferences as they are influencing our preferences.

When companies such as Alibaba have such a large span of influence over our purchasing decisions, it raises the question of whether the government should intervene to prevent an effective monopoly.

Very interesting. I’d posit that we should all be concerned about the amount of power and data that is controlled by so few people. (Alibaba, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google, etc.)

Whenever I see words like personalization, the couple of things come to mind:

1 – What data (about the user) is being utilized to calculate that personalization effect on the app?

2 – How is that data being collected? Is it just the Taobao app data that is being used? Or is the app collecting data from other apps on the user’s phone?

I think the users are not realizing the reach of these apps in their personal life. There is a fine line between using user data and exploiting it for profits. Are there any regulations or data privacy laws in China to prevent misuse of this data being collected on users?

On other note, I agree with a lot of people above that the app does not know us better than ourselves. It just offers new products to a particular demographic. Its similar to a sales person introducing a new product to us on the street or in a retail shop. That does not mean that the sales person knows us better than ourselves.