A Tablet a Day Keeps the Dropouts at Bay: How Bridge Leveraged Tech to Become Africa’s Largest School Chain

Cashless $6-a-month payments for Kenyan private school tuition? Scripted, US-developed lessons pushed to Ugandan schoolteachers' tablets? The equivalent of 32% more schooling in English in a year? Thanks to technology, Bridge International Academies claims to have it all.

Since opening its first school in 2009, Bridge International Academies (Bridge) has become Africa’s largest school chain, serving 100K+ students in 400+ schools across Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria. A for-profit, Bridge says its schools cost an average of $6 per pupil per mont h[i].

h[i].

Bridge claims to provide the equivalent of 32% more schooling in English and 13% more schooling in math in one year.[ii] In addition, it has raised $100M+ from big-name investors (see Figure 1)[iii] and won accolades from OPIC’s Development Impact Award to The Economist’s Social and Economic Innovation Award.[iv] So what has contributed to Bridge’s success? Most significantly, its unique, technology-enabled approach.

Content Development and Distribution: Thanks to technology, Bridge content can be developed and standardized remotely. Experts from local countries and Cambridge, MA work together to develop Bridge’s curricula, which are based on government standards. Lesson plans (teacher scripts) and assessments are then pushed via internet from a team in the US to Bridge locations halfway around the world.[v]

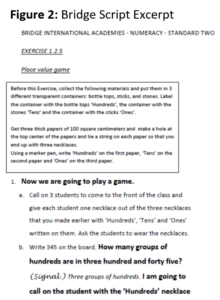

Teaching and Tracking: Every Bridge teacher receives a data-enabled Nook tablet that syncs with Bridge headquarters, allowing teacher script  delivery and headquarter insights into classroom data (e.g., lesson pacing).[vi] As shown in Figure 2,[vii] the script is extremely prescriptive – telling teachers exactly what to prepare, say, and do (down to pronunciation and physical gestures)[viii] – and teachers are trained not to deviate from it. In Bridge’s opinion, this ensures a consistent and optimized experience across schools while reducing the burden of lesson planning on teachers, which is particularly important in countries like Kenya where access to high quality teachers is limited.[ix] These tablets also track data such as student attendance and serve as a source of accountability for teachers; if a teacher doesn’t sign into the tablet one day, Bridge can call the teacher to determine why.[x]

delivery and headquarter insights into classroom data (e.g., lesson pacing).[vi] As shown in Figure 2,[vii] the script is extremely prescriptive – telling teachers exactly what to prepare, say, and do (down to pronunciation and physical gestures)[viii] – and teachers are trained not to deviate from it. In Bridge’s opinion, this ensures a consistent and optimized experience across schools while reducing the burden of lesson planning on teachers, which is particularly important in countries like Kenya where access to high quality teachers is limited.[ix] These tablets also track data such as student attendance and serve as a source of accountability for teachers; if a teacher doesn’t sign into the tablet one day, Bridge can call the teacher to determine why.[x]

Payments: Through its own research, Bridge found that other school managers spent more than half of their time being a “cash register”: collecting tuition, paying teachers, and paying vendors.[xi] Therefore, it decided to make all of its schools “cashless”. Bridge leveraged mobile banking technology (such as M-PESA in Kenya) and centralized relevant functions to automate tuition payments from parents and payroll payments to teachers.

Unfortunately, all that glitters may not be gold. Citing concerns about sanitation, curricula standards, infrastructure, and teacher qualifications, Uganda’s High Court ordered Bridge to close; after losing its appeal earlier this month, Bridge may have to shutter its 63 schools in Uganda, which serve approximately 12K students.[xii] Additionally, many question the fundamentals of Bridge’s model, believing that the poor shouldn’t have to pay for education or that tablet-based teaching strips teachers of necessary autonomy and leads to over-standardization and a lack of individualized student attention. Some also disbelieve Bridge’s data, saying its average price is more than $6 a month and its impact claims (based largely on self-funded studies) are misleading or inaccurate.[xiii]

Going forward, Bridge should use technology to help address these issues, whether that means proving them wrong or accurately identifying the sources of the problems and fixing them. Its existing technology infrastructure and resources can be used to better monitor and identify potential problems and relay information to independent evaluators who can confirm (or discredit) Bridge’s impact claims.

(798 words)

[i] Bridge International Academies, “Mission”, http://www.bridgeinternationalacademies.com/academics/philosophy/, accessed November 2016.

[ii] Bridge International Academies, “Academic Results”, http://www.bridgeinternationalacademies.com/results/academic/, accessed November 2016.

[iii] Ashina Mtsumi, Abraham Ochieng, and Sylvin Aubry. “Kenya’s support to privatization in education: the choice for segregation?” The Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, September 2015, http://globalinitiative-escr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/11/150930-EACHRights_Hakijamii_GI-ESCR-Kenya-Parallel-report-ACHPR-privatisation-right-to-education.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[iv] Bridge International Academies, “Awards”, http://www.bridgeinternationalacademies.com/ acclaim/awards/, accessed November 2016.

[v] Christina Kwauk and Jenny Perlman Robinson, “Bridge International Academies: Delivering Quality Education at a Low Cost in Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda”, Center for Universal Education at Brookings, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/BRO1600220BridgeFINAL-1.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[vi] Bridge International Academies, “Philosophy”, http://www.bridgeinternationalacademies.com/academics/philosophy/, accessed November 2016.

[vii] V. Kasturi Rangan and Katharine Lee, “Bridge International Academies: A School in a Box,” HBS No. N9-511-064, (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010), p. 17.

[viii] Eli Wolfe, “Academies-in-a-Box are Thriving – But Are They the Best Way to School the World’s Poor?”, California Magazine, April 15, 2014, accessed November 2016.

[ix] Gayle H. Martin and Obert Pimhidzai, “Kenya”, Service Delivery Indicators, July 2013, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/AFRICAEXT/Resources/SDI-Report-Kenya.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[x] Matina Stevis and Simon Clark, “Zuckerberg-Backed Startup Seeks to Shake Up African Education,” The Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2013, http://www.wsj.com/articles/startup-aims-to-provide-a-bridge-to-education-1426275737, accessed November 2016.

[xi] V. Kasturi Rangan and Katharine Lee, “Bridge International Academies: A School in a Box,” HBS No. N9-511-064, (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010), p. 11.

[xii] Africa Bureau, “Uganda court orders closure of low-cost Bridge International schools,” BBC, November 4, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37871130, accessed November 2016.

[xiii] Signatory Organizations in Uganda and Kenya, “Just $6 a month?: The World Bank will not end poverty by promoting fee-charging, for-profit schools in Kenya and Uganda”, May 2015, http://globalinitiative-escr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/05/May-2015-Join-statement-reaction-to-WB-statement-on-Bridge-14.05.2015.pdf, accessed November 2016.

It is heartening to see that Bridge taking big and bold strokes in their attempt to ensure every child’s right to education. The move by the Ugandan High Court is disappointing yet predictable, given the entrenched interests of various stakeholders.

Going forward, I think a key lesson for Bridge is that it needs to work closely with all required approval agencies or ministries. Unlike Uber and Lyft packing up and leaving Austin, Texas in protest against the requirement of fingerprint-based background checks, Bridge cannot do the same. This is particularly if Bridge keeps in mind what (I hope )matters most to them – ensuring that every child on the planet is able to get access to the basic right of education.

TD21,

Thanks for writing this post – very informative on a business that seems to aim at “making a difference in the world”. You do a great job of describing both Bridge International’s strengths (cashless payments, consistent experience, teacher accountability, overall increased education etc) and weaknesses (over-standardization and lack of individualized student attention). I also liked your recommendation of leveraging existing infrastructure to “better monitor and identify potential problems” but it was not immediately clear whether this is feasible, and if so, why the company isn’t already doing this. For example, perhaps teachers are not properly trained at monitoring and identifying problems and this would require additional investments/resources.

Additionally, this post reminded me of our class discussion on IBM’s Watson machine. In particular, I wonder the extent to which Bridge’s current technology may soon become obsolete and replaced by machine learning. According to your post, the script Bridge’s tablets use is “extremely prescriptive – telling teachers exactly what to prepare, say, and do (down to pronunciation and physical gestures) – and teachers are trained not to deviate from it.” This approach seems to be in line with traditional uses of machines, which function as a result of direct human input. I wonder whether you could create a machine that learns from various algorithms to pull the most relevant teaching lessons together. For example, would it be possible to create a tablet that can determine the best direction a class should go based on past successful comments?

While we may still be far away from a self-driving teacher, is it too farfetched to imagine a world in which teaching may become more automated without increasing standardization? Considering how difficult it was for Watson to figure out black/white questions it seems that this may not be a current possibility. However, I do think that learning is at its best when there is spontaneity in classroom discussions and content is not predetermined. I wonder – could you imagine a case method being taught by a computer in the not-so-distant future? Food for thought…

TD21, thanks for this great post on an exciting effort to improve educational opportunities for students in developing countries. Though there definitely seems room to perhaps incorporate machine learning to improve its educational teaching lessons, that may be a bit of a ways off. Nearer term, though, there seem to be lots of opportunities for A/B testing a la Team New Zealand to learn how different lessons plans work or don’t. Because of its standardization of lesson plans and the teacher fidelity to them, Bridge has a rather unique opportunity among educational providers to learn in this way.

Your suggestion to better use technology to report and address problems seems a like good one. Perhaps Bridge could set up local numbers that parents could text with concerns (teacher absences, sanitation, etc.)? I wasn’t sure if Bridge currently has that sort of technology infrastructure set up, but doing so could not only give it a chance to learn more about its mistakes but also try out different ways to engage and inform parents about their child’s learning. Simple text based messaging has been show to make dramatic differences to early literacy (https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/one-step-time-effects-early-literacy-text-messaging-program-parents-preschoolers) and is increasingly being used to help improve attendance in schools (http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/24/technology/an-app-helps-teachers-track-student-attendance.html).

I really like the topic your article is addressing. In February this year I visited 5 different elementary schools in Nairobi, Kenya. I went there to visit a school we raised money for. This charity sponsored school was in one of the Nairobi slums where families live for less than $1 per day. I wanted to meet the children, see how they learn and understand the conditions they live in. Besides the charity school, I visited a public-state school and a private school. The private schools in Nairobi are well equipped, the teachers are educated, some of them are international, and the children come from middle to high income families.

I believe Bridge is targeting the public schools. The public schools in Kenya are in very poor conditions compared to the developed world, many times there are 50 children per class, the teachers are untrained and there is no standard curriculum across the schools. The school I visited there was one computer room with 20 donated computers for 500 children. Because the access to high quality teachers and equipment is limited, companies like Bridge can have an enormous impact on educating the youth. I think it is a great idea that Bridge is preparing a script abroad and then sending it to the teachers who can access it from their notebook. One advice I would give to Bridge is to leave some flexibility to the teachers as students in one school can learn slower than in another school.

Tracking students attendance via the nootebook is a great help to the teachers and the school. But I wouldn’t hold the teacher accountable for low attendance. In one case I have seen that children didn’t show up in school because their parents sent them to make money instead. In another case a girl didn’t come to school because her mom took her to a hairdresser to get her braids done. Having a nice long hair is a social status in Kenya, and some parents value that more than education. For these reasons the teachers must go often beyond teaching, the teacher has to be a good psychologist as well. Bridge needs to understand the dynamics in order to create an efficient learning tool.

I believe charging the parents $6 or less per month creates a good incentive to send the child to school. But if Bridge charges too much many families will not be able to provide eduction for their children. Even if education is for free some families will not be able to afford it. Sending their children to school means they don’t get money the children could bring home if they went to work instead.

Bridge could add to their offering classes for adults, and design scripts that can be presented to the parents. This classes would be offered for free and they would be provided after the school hours. The purpose of the free classes is to increase the knowledge of the adults and also pass a message that education contributes to the welfare of the society.