Ecofriendly Fast-Fashion: A Real Possibility or an Oxymoron?

Exploring the tension between fast-fashion and sustainability: can both co-exist?

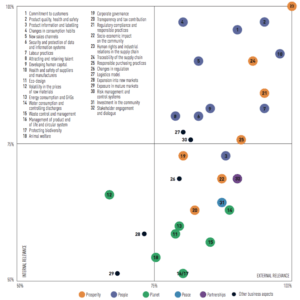

Fast-fashion companies should keep a close eye on climate change. This post explores why through the lens of Inditex, the parent company of highly successful brands such as Zara, Massimo Dutti and Bershka. Inditex’s business model is notably strong, with ROE averaging ~27% over the past five years, but its operations will soon face significant challenges through the physical manifestations of global warming, including but not limited to, water scarcity – a topic this post will analyze in greater depth.[1] While Inditex is engaged in a host of initiatives related to conserving water and improving sustainability more broadly, there is still a gap between the relevance the company internally attributes to green/planetary issues and the importance external parties, including consumers, place on these (see chart below).[2] This disconnect suggests the firm could be more strategic in its marketing positioning in order to convert the challenges presented by climate change into opportunities.

Inditex will inevitably be affected by global water scarcity and its impact on raw material sourcing and production. According to the World Bank, “currently, 1.6 billion people live in countries and regions with absolute water scarcity and the number is expected to rise to 2.8 billion people by 2025.”[3] Although Inditex does not disclose raw material purchases on a country-level basis, Southeast Asia concentrates the highest percentage of suppliers (~48%).[4] Bangladesh for example, has the highest number of workers forming the staff of manufacturers working for Inditex (386,916)[5] . Bangladesh is vulnerable to water shortages because its largest rivers originate in major developing countries such as India and China where demand for water is most likely to outstrip supply, creating potential conflict. Another exacerbating factor relates to fluctuating rain patterns, with monsoons during warmer seasons susceptible to extreme weather. According to the UN’s latest briefing, “during severe foods, the affected area may exceed 53,000 km2 or 37% of the country and in extreme events… about 66% of the country is inundated.”[6] This matters because roughly 88% of the country’s water is directed towards agricultural production and shortages due to unstable irrigation pose an amplified risk given high levels of manufacturing.[7]

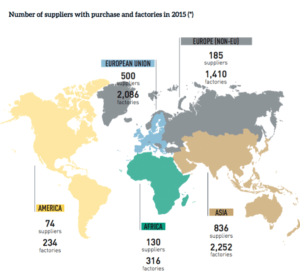

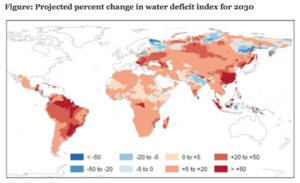

The counterargument can be made that Inditex has diversified risk given that the “1,725 suppliers and 6,298 factories that make up the Inditex supply chain are located in over 50 countries”.[8] The greater point however is that the supply of water is expected to fluctuate significantly by country (see map below)[9] . The increased variability of water supply could prove hard to predict and manage across such a complex supply chain. Additionally, some types of raw materials may be more vulnerable to changes in environmental conditions than others, further increasing uncertainty. Inditex has already taken steps to increase operational efficiency, as exemplified by its results with its local partnership in Bangladesh where “13.4 MM m3 of water a year was saved avoiding the emission of 169,400 tons of CO2.”[10] Other efforts include more efficient design and selecting raw materials that consume less, such as recycled cotton: “water consumption in the production process

for recycled cotton is

approximately 80%

lower than in traditional

cotton production

”.[11]

The overarching question is how the company can create opportunities from an increasingly strained environment. The good news is that consumers are willing to pay more for a product “from a company known for being environmentally friendly” as opposed to other drivers.[12] Inditex could consider raising prices to capture this value, but there is somewhat of a ceiling given the extent to which the company promise emphasizes affordability. Higher margins would however provide additional sources of revenue to be invested in innovation directed at developing high quality, sustainable products. Additionally, Inditex should consider incorporating sustainability efforts to a greater extent in its marketing strategy through advertising campaigns built on raising awareness. A consumer should not have to dig deep into Inditex’s presentations to learn about the myriad ways the company is tackling sustainability. However, the latter proposition may increase sales levels, which could run contrary to the overall goal of fighting climate change.

So can Inditex’s operational model co-exist with sustainability? Inditex has traditionally been categorized a fast-fashion company associated with short-term shopping behavior. One solution may be to create incentive systems through which customers can trade in their old clothing for discounts on new purchases, reducing the overall waste in the system. This could potentially help the company improve sales while also providing responsible alternatives on the sustainability front. The company could both utilize its current store locations and have a central mailing department that you can ship your old clothes to – capitalizing on changes in consumer behavior in an e-commerce era. In summary, climate change poses critical decisions for fast-fashion and long-term success will depend on innovative thinking while incorporating sustainability to current business models.

Word Count (796)

References

[1] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 20

[2] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 161

[3] World Bank Website: http://water.worldbank.org/topics/water-resources-management/water-and-climate-change

[4] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 37

[5] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 145

[6] UN Website: http://www.unwater.org/fileadmin/user_upload/unwater_new/docs/Publications/BGD_pagebypage.pdf

[7] UN Website: shttp://www.unwater.org/fileadmin/user_upload/unwater_new/docs/Publications/BGD_pagebypage.pdf

[8] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 40

[9] World Bank Website: http://water.worldbank.org/topics/water-resources-management/water-and-climate-change

[10] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 66

[11] Inditex 2015 Annual Report, Page 63

[12] Nielsen, “The Sustainability Imperative: New Insights on Consumer Expectations”, October 2015

I agree with you that beyond looking at the implications of sustainability on Inditex’s operations, in truly determining whether Inditex’s model can co-exist with sustainability, we have to take a step back and look at the customer promise of Inditex – to provide up-to-the-minute designs at extremely low price points. This has encouraged shoppers to not only expand their wardrobes vastly, but also refresh them quickly. Incentives to encourage recycling of consumers’ old clothes only helps resolve one end of the problem – there are still considerable resources involved to generate these “disposable” pieces of clothing that the brands under Inditex sell. For Inditex to truly work be aligned with sustainability, a fundamental change to its customers promise may ultimately be necessary.

I think that the title of this article captures perfectly my problem with this industry. I feel like fast-fashion is fundamentally set up so that it cannot be eco-friendly. With that said, I will have to caveat my own statement with one exception: fast-fashion moves into luxury. My opinion is that today, fast-fashion is almost synonymous with cheap fashion where most consumers purchasing fast fashion expect it to come at a low price. If Inditex tries to move towards a more sustainable operating model, it would need to invest more along various processes in its’ production line. This would translate into higher costs for the customer which may or may not be something that they are willing to pay. I think this is especially true given the very nature of fast-fashion as it signifies a fast turnaround of clothing. I don’t see a way to argue or convince customers that it makes sense to pay more for a product that is not of higher quality and that customers expect to use for a short period of time. Although studies have shown customers are willing to pay more for sustainable products, customer behaviour in the realm of fast-fashion may be more difficult to change. As such, although sad to say, I don’t think that fast-fashion as of today can become a sustainable industry.

While I agree with Orienne in the short term, I question whether this holds true when assessing long term costs. Certainly, attempting to use recycled material may increase cost that would eat into margins if not passed on to consumers; however, innovation in material or manufacturing processes that mitigates risk to water shortage may decrease the price dependency on external factors. This could put Inditex at a cost advantage relative to its competitors. As mentioned in the article, Inditex is already at an advantage to unpredictable shortages due to the breadth of suppliers and manufacturing locations. Similarly, if Inditex can develop processes that consume less water they may be less susceptible to price fluctuation when water availability changes. On the other hand, innovation bring increase near term costs. This then begs the question of how much Inditex can spend to develop new processes and materials while retaining a margin attractive to shareholders in the near term. Are they able to articulate a long-term vision that may mean less profit today?

Alternative to innovation in materials and process, could Inditex work more actively with suppliers to increase efficiency of water utilization? Reducing the risk of impact from water shortage on suppliers may make for more stable costs of raw materials, which can be attractive to shareholders. This would require an investigation of cost relative to benefit, however reducing risk upstream may prove to be worth the investment in working with suppliers. Inditex could explore cost sharing in development of mitigations that may make for more stable supply downstream.

I wonder when a company like Inditex is driven to invest in water conservatoin solutions. Would they be proactive and invest in drip irrigation systems for their cotton partners now, knowing shortages can hit any of their loactions in a given year, or are they going to wait, because the cost of infrasturcture is too high?

Looking back on the H&M case; few member of the class knew there was a 15% in store discount available for recycling 3 pieces of clothing. I think there would be a lot of benefit to having a recycling incentive, but I am not sure how viable it would be in the current fashion industry. The “30 Wears” movement is another alternative to responsible purchasing and use of clothing items. This may seem counter-intuitive to a fast fashion brand, but it could be another way to bring resource awareness to the public.

Maria, your post reminds me of our class discussion about sustainability at IKEA. Although Inditex is making strides to address climate change and reduce its carbon footprint, the very nature of its business at odds with this. As you stated, fast fashion is wasteful and is paradoxical with with sustainability. Eventually, if the clothing trade idea you proposed or other recycling efforts gain traction, the company will only be able to offset its negative environmental impact – but not necessarily ever get to a net-positive impact result. I just wonder if this is a deterrent to action. As we discussed in class, if you simply disengage with the furniture business or fast fashion business, other competitors will simply take your place. Anyway, I’m still on the fence on what Inditex’s role is within the sustainability space – thanks for writing a thought-provoking article!