9. Will Market-Creating Innovations Continue Creating Jobs?

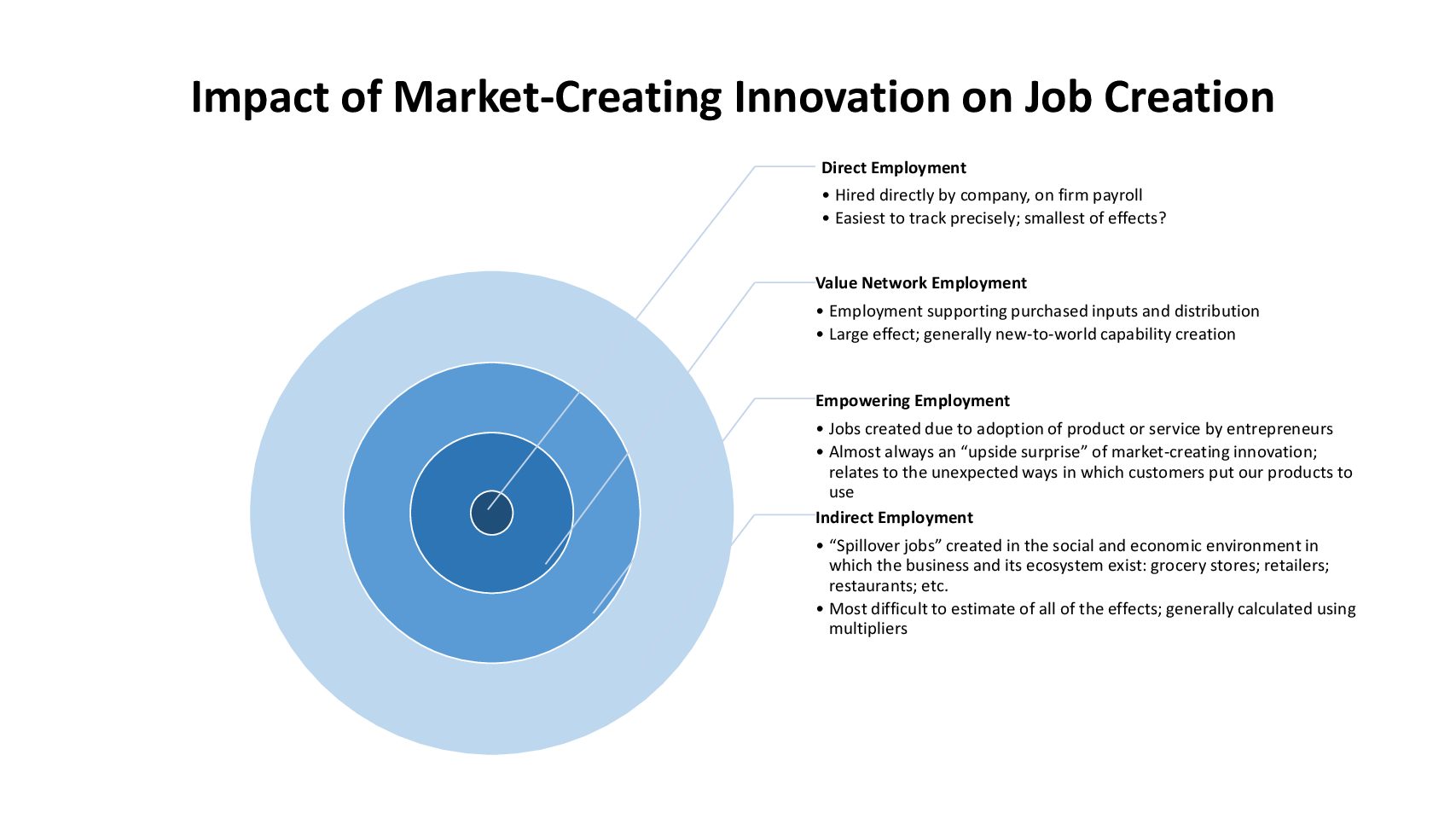

Please review this graph.

One of the questions we’ve been exploring the most intensively is “Why do market-creating innovations create the most jobs?”, and we think we’ve come up with the answer. This is a tangled subject area—a lot of the research that is done here is sponsored by companies, politically-motivated (especially now!), and kind of imprecise, but bear with us:

As we lay out in our original article, different types of innovation have very different impact on job creation, as well as on economic growth. Efficiency innovations destroy jobs; performance-improving innovations create jobs, but only marginally, due to their substitutive nature; leaving market-creating innovations to do the heavy lifting of job creation. And they do, in four ways, as we depict in the chart at the top of this thread. Think of a market-creating innovation like a stone thrown into a pond, with employment effects emanating out like ripples from that stone, each larger than the last. So, from smallest to largest:

- First, they create jobs due to direct employment—increasing employee headcount at the innovating company. Surprisingly, this might well be the most modest way in which they contribute to job growth.

- Second, they create jobs in the value network—the supplier networks and distribution channels through which the product or service is sourced and sold. Because these channels are generally new-to-the-world, this effect can be large.

- Third, and most distinctively, they have an empowering effect on employment—they create jobs through their adoption by aspiring entrepreneurs. From the seamstresses who used the Singer sewing machine to supply the earliest mercantile shops to the app developers who feed the iPhone ecosystem today, this effect is powerful and almost always impossible to estimate in advance.

- Finally, market-creating innovations share the indirect employment effects of performance-improving innovations—the “spillover jobs” in local economies that house workers with more money to spend. This effect might well be the largest of all, though it is also the most diffuse and difficult to track.

We’ve gotten good reactions from people who work in this field for a living and felt confident about its description in the past, but in an era of A.I. and robotics, will it still hold true?

With machine learning research yielding more clues about what we could expect from technology in the future, the way we think about the role of humans in innovation will also have to evolve. Ben Thompson puts it better than I can, so I’ll leave an excerpt from his blog here:

“Just as we designed the cotton gin, so we designed accounting software, and automated manufacturing. And, in fact, those are all related: all involved overt design, in which a human anticipated the functionality and built a machine that could execute that functionality on a repeatable basis… Machine learning is different. Now, instead of humans designing algorithms to be executed by a computer, the computer is designing the algorithms… the truth is that humans have made machines to replace their own labor from the beginning of time; it is only now that the machines are creating themselves, at least to a degree.” (Source: https://stratechery.com/2017/the-arrival-of-artificial-intelligence/)

I believe we’re still far off from reaching the level of artificial intelligence that would immediately replace human jobs that involve thinking and emotional judgment, but we certainly will get to a point in the short-term where manufacturing and design of machines could easily be done by other machines. I could see this kind of innovation definitely resulting in a net destruction of jobs.

The question, though, is whether this kind of innovation can be counted as a market-creating innovation. From what I can see, machine learning doesn’t seem to target nonconsumption nor empower those who previously didn’t have access to the forerunner product.

The Economist seems to sit in the middle ground — that AI will lead to neither huge net gain nor net loss of jobs.

The Impact on Jobs: Automation and Anxiety — https://goo.gl/h5MAZc

“So who is right: the pessimists (many of them techie types), who say this time is different and machines really will take all the jobs, or the optimists (mostly economists and historians), who insist that in the end technology always creates more jobs than it destroys? The truth probably lies somewhere in between. AI will not cause mass unemployment, but it will speed up the existing trend of computer-related automation, disrupting labour markets just as technological change has done before, and requiring workers to learn new skills more quickly than in the past.”

Technology is becoming easier to use. We can thank Apple for starting a new breed of UI, UX, and product managers who are in high demand.

There will be jobs you’ve never even heard of emerging in the market.

And all technology needs a human to operate, or educate others.

Engineering is another sector I believe will grow. With nimble commercial entities servicing niche market needs, a truly great customer journey needs design thinking.

Creative people will finally be compensated for their natural talent. You can’t teach that kind of intelligence, and creatives are the product differentiator in a noisy world of heuristic decision makers.

I believe the theory will hold true in an era of robotics and AI for several reasons. I’ll reference the chart to explain my thoughts.

-Direct employment may or may not decrease. Even in the most complicated manufacturing processes, like the manufacture and assembly of a 787 requires supervision and possibly intervention. Yes, the army of workers with rivet guns have gone away–but their replacement has been a smaller workforce of highly skilled workers to set up, supervise, trouble-shoot, and repair if need be. No matter how “perfect” we design equipment, there are always tight spots and nuances that only a person can attend to. Another factor to consider is the replenishment requirements of sophisticated equipment. Simply put, the faster it works, the more it needs to be resupplied–and maintained. For example, during WWII the Germans used a machine gun–the MG-242–that featured an extremely high rate of fire. It fired twice as much ammunition as the US model, and required the crew to frequently change barrels due to heat. However the Germans used slow, inefficient horses to resupply the front lines. Automation gives greater capabilities, but with a cost.

-Value Network Employment. If my interpretation is correct, this deals with the added jobs due to inputs. In the 787 example, Boeing lost jobs in some specialties. However with outsourcing the components for the jet, jobs were added in other parts of the world. At first glance, this may seem like a job destroyer. However with efficient component production methods, Boeing was able to produce more aircraft. This caused them to open a new assembly facility in Charleston, SC and add assembly staff there. So if my read is correct, an efficient, growing value network may increase direct employment numbers, even if the production is mostly automated.

-Empowering Employment. Looking at the 787 Dreamliner, it’s fair to say this NMI brings a lot of jobs due to the efficient manufacturing. For example, the upstart international carrier Norwegian Air (who is currently in the middle of a fair labor practice dispute) is able to use the 787 to reach markets that were previously considered unprofitable by flag carriers. The unexpected “upside” was that smaller cities would be given access to international travel.

-Which leads to Indirect Employment. The capabilities of the 787 make cities like Austin, Texas a contender for long-haul international flying. This has a tremendous effect on an up-and-coming city. Airports are made larger, generating construction and trade jobs. Ancillary services, like aircraft servicing grow jobs. Business relationships often lead to increased staffing or space requirements. And roads, businesses–like car rental agencies or Uber drivers see an increase in demand. That’s only the tip of the iceberg, too. Airlines grow, too.

So for an increase in automation or AI, we will probably see some jobs go away. However the net result will be more, better paying jobs.

One last observation: Not all NMIs create the intended “ripple effect.” For example, the Segway scooter met every metric of the graph, yet it belly-flopped because there was not an underlying need for it.

Thank you for the opportunity to share my thoughts on the pressing issue of job creation. It is a worthy effort to help make the lives of everyday people more fulfilling. Thank you, Professor Christensen & staff.