Vigilante App: What Happens when Ordinary Citizens Take Crime Fighting into their Own Hands?

While the app’s crowdsourcing platform has brought more transparency and crime awareness for local residents, it has also raised deeper concerns and doubts around the idea of crowdsourced vigilantism.

The app, Vigilante, was created by Andrew Frame who sought to raise crime awareness in New York City by informing users of dangerous areas to avoid. The App obtains information from two main sources – 1) curated 911 calls and public police database, and 2) user updates and uploads of live videos from the crime scene, which could also be shared on social media. The users could search incidents – labeled by the type of crime – that occurred in their area through a map interface and comment on other users’ videos and reports. By leveraging the crowd, the App aimed to offer real time, hyperlocal crime information that had not yet been reported to the local police.[i]

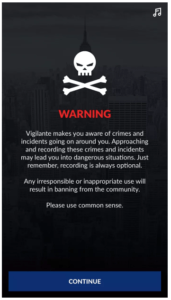

When Vigilante was first launched in October 2016, the app’s blog post quoted a former police officer, who said that “average and ordinary citizens should approach the problem of crime as a group.”[ii] Vigilante also promoted a dramatized video of a group of average citizens that used the Vigilante app to stop a violent assault from happening. Consequently, the launch faced serious backlash from NYPD, and was shortly removed from Apple’s app store a week after the launch due to concerns around user safety[iii].

Months later, the crime awareness app relaunched under the new name “Citizen”, claiming that it has deemphasized potential involvement from users by making the “report incident” button less visible in the app. The app now warns users to “never approach a crime scene, interfere with an incident, or get in the way of police.”[iv] The app has now expanded to San Francisco, and has recorded a number of positive instances where the crowdsourced information has actually helped the police department. However, major concerns still remain:

- Are the cosmetic changes that Citizen made enough to deter its users from voluntarily getting into dangerous situations? By providing a platform for average citizens to post crime scenes, the app may naturally attract those users who want to “play the hero” or those who would put themselves in harm’s way to capture the “perfect footage” for social media. These actions not only put the users’ lives in danger, but could also hinder the police’s rescue efforts[v].

- Taking videos and photos of the crime scene could also jeopardize the lives of the witnesses and victims in the videos. What happens if the identity of crucial witnesses was captured and shared on social media? This could endanger their lives and impact their ability to collaborate with the police.

- The app also allows room for users to interpret the crime scene itself, which may lead to racial profiling and other human biases. Users may wrongly describe the physical features of the criminal on scene or identify the wrong criminal in their reports. Apps such as NextDoor[vi], or GhettoTracker[vii] for example, have faced these strong criticisms around their tendencies to advocate racial profiling and racist comments online.

While Citizen has certainly assisted the police and has helped users avoid danger through its increased transparency on the platform, the crowdsourcing model, if left unchecked, could also yield serious consequences. In order for this app to succeed, Citizen needs to put in place filters for its user-posted content. Photos that contain identifiable faces of individuals should be handed directly to the police and omitted from the social platform. Personal report forms should focus on objective descriptors such as what the suspect is wearing, height, gender, license places, his or her actions, etc. Citizen should also partner with nonprofit organizations like WITNESS, which trains people on how to ethically use video to expose human rights violations, and create mandatory training videos for its users. And finally, Citizen should continue to work with the city government to gather surveillance data captured in public areas to cross-check users’ inputs. Only incidents that pose a severe threat and with the highest likelihood of reoccurrence should be posted on the website.

Endnote:

[i] Business Wire. “First Crime Awareness App Launches in NYC”. October, 26, 2017. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20161026005357/en/Crime-Awareness-App-Launches-NYC-Offering-Real-Time

[ii] TechCrunch. “Banned Crime Reporting App Vigilante Returns as Citizen.” https://techcrunch.com/2017/03/10/banned-crime-reporting-app-vigilante-returns-as-citizen-says-its-report-incident-feature-will-be-pulled/

[iii] Rilley Top 10. “The Citizen App”. December 3, 2017. http://reillytop10.com/2017/12/03/the-citizen-app/

[iv] The Outline. “Crime Video App Vigilante Relaunches as Citizen”. March 9, 2017. https://theoutline.com/post/1212/crime-video-app-vigilante-relaunches-as-citizen?zd=1&zi=266vuz6c

[v] DW. “’Citizen’ crime apps – a boon or a curse for police?”. October 3, 2017. http://www.dw.com/en/citizen-crime-apps-a-boon-or-a-curse-for-police/a-37884343

[vi] NPR. “Social Network Nextdoor Moves To Block Racial Profiling Online”. August 23, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/08/23/490950267/social-network-nextdoor-moves-to-block-racial-profiling-online

[vii] Huffington Post. “’Ghetto Tracker,’ App That Helps Rich Avoid Poor, Is As Bad As It Sounds”. September 4, 2013. http://archive.eurweb.com/2013/09/yes-the-ghetto-tracker-app-actually-exists-but-under-a-new-name/#