TED leads in a winner-take-all world of conferences

How TED became a household name, transformed itself into a media company, and upended the conference business by giving away its product for free.

In June of 2006, well before most conferences were experimenting with how to bring their business to the internet, the TED Conference posted its library of talks to TED.com for anyone to view, free of charge. At the time, the thought of giving away the content was heretical within the industry: after all, attendees paid good money for the privilege of seeing those talks.

Of course today TED, which stands for Technology Entertainment and Design, stands out as the 800-pound gorilla of conferences. Chris Anderson, TED’s owner and curator, has spawned a giant media business in distributing recorded “TED Talks,” a number of spin-off sub-conferences such as TED Global or TED Women, more than 3,000 “TEDx” events, organized and produced worldwide by unpaid volunteers, a series of talks presented as theater on Broadway in NYC, and numerous copycat ideas conferences.

Building Value

All of this success grew from a fundamental insight about how digital technology was about to change not only the business of running a conference, but also the careers of authors, professional speakers, consultants, and academics. Actually, it’s just a lesson from Econ 101.

Basic microeconomics tells us we’ll pay more for something if there’s less of it available: scarcity creates value. The Internet took most of the things that conference organizers thought they were charging for–presentations, education, handouts–and made them abundant.

And if anyone could go to YouTube and find a talk by, for example, Bill Gates or Jane Goodall, Anderson figured they might as well be watching a talk from the stage of TED.

By giving talks away as free videos online, TED created tremendous value for the millions of people who were now able to watch professional presentations by recognized global experts. TED created value for itself: people who had never heard of TED would see, in the form of each talk, a kind of celebrity endorsement ad for the conference. TED also built an audience that creates value for its speakers in that TED is a platform for becoming famous or widely sharing an idea.

But the shift that TED has undergone is more fundamental than throwing videos up online. They’ve taken their content and made it a digital good. Which means TED can profit from the content’s abundance, not its scarcity.

Capturing Value

TED is changing itself from a conference company* to a media company. It is able to charge companies for advertisements on its videos, which have been viewed more than a billion times, and are distributed not only through their own website, but through other platforms like AppleTV, Xbox Live, and even as audio recordings on NPR.

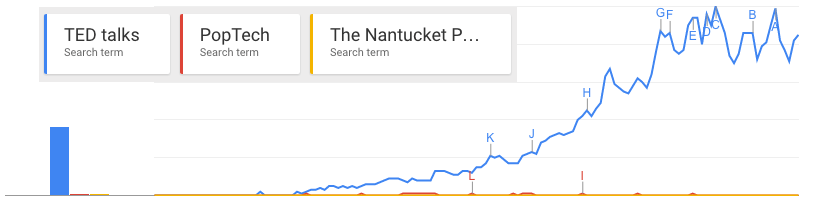

By building such an audience for its presentations, TED has also built a strong and defensible asset. The popularity of TED talks effectively “crowds out” potential competitors; there is not much room in the market for talks from competing conferences like PopTech or The Nantucket Project, even though the latter draws speakers like Tony Blair. TEDx Talks given by non-famous speakers regularly outperform videos from heads of state given at other events with no equivalent platform.

In short, TED is a star maker.

In the past, conference speakers were paid for their time and work by the conference. Conferences paid speakers because they could charge a high ticket price that businesses were happy to expense: after all, when else was the employee going to have a chance to learn from the likes of Bill Gates? Many businesses and trade conferences must still offer their speakers payment even though it’s much harder to recover the cost in registration fees. But TED? TED pays in fame.

TED gains other benefits from its widespread audience. Because TED is a widely recognized consumer brand, it is able to capture more value from its conferences than before by selling conference registrations as a luxury good. In other words, for some people there is a four or five thousand dollar premium on being able to say, “I go to TED.” In 2012 revenue from conferences (which includes the main TED event, and a few associated affiliate events produced by TED itself) was about $27.8 million.

That’s still more than it draws in from other revenue sources, leaving only $17.3 million from all other operations. But that is misleading, too. TED is owned by the nonprofit Sapling Foundation, and solicits conference attendee organizations for tax-deductible donations in the form of larger registration prices, ranging as high as $150,000. These donations are grouped with “conference” revenue, but in reality TED is able to capture this value primarily because of their video platform.

TED is unquestionably a digital winner in the conference and media industries. Its willingness to experiment with both format and context is ongoing — as evidenced by their recent announcement to bring the TED Talks format to Broadway theater in New York. As software continues to eat portions of the traditional conference and media business, and with the advent of new technologies like virtual reality, TED will need to continue to evolve with it.

——

* They’re technically a nonprofit, but a highly profitable one. ^

This is fascinating, and a great history on the rise of the TED phenomenon. I agree that they truly were ahead of their time by being willing to put their content online for free in order to drive customer awareness and build what, more-or-less, became a cult following of their various publications. As a non-for-profit, I do wonder if the market incentives are in place for them to remain at the top of this game for the foreseeable future. Again, I completely agree that they have managed to create a ‘luxury good’ when it comes to their conferences, but this seems like an open space that many for-profit companies will attempt to capitalize upon. Only time will tell if they can successfully protect their brand against future incumbents, but they were definitely an early winner in this space.

Any time you’ve got a large profit margin, it’s inherently attractive to competitors, but I think their position is pretty defensible. There are actually a number of for-profit (and non-profit) outfits looking to get into the same market, including The Nantucket Project, Founders Forum, Summit Series, The DO Lectures, Future in Review, and others.

I think what makes TED’s position good is that there’s only so much appetite for TED-style events as a *consumer brand,* which is what they’re able to extract their premiums from. Without wide public recognition and distribution, competing events will find it tough to charge similar premiums (and pay similarly reduced fees for equal speaking talent).