Spotify’s Business Model – Competing With Network Effects

Spotify leveraged network effects to gain a massive user base, and amass (almost) the entirety of the world's popular music collection. Now the company is seeking to capture value from its users, which as it turns out are the ones that pay $9.99 per month for a premium subscription. But the incentive system between the company and its users is broken.

Digital innovation has drastically reallocated the money associated with music consumption. With physical releases, record labels captured most of the revenue by implementing expensive marketing campaigns and convincing a large swath of users to pay $10-20 for an album upfront. They got paid the same amount, regardless of how much the user ever actually listened to that album. In the consumption model, however, how many times a song gets listened to is exactly how labels and artists make money from official releases. Enter the new players in the industry to capture value: tech-enabled music platforms like iTunes and Spotify.

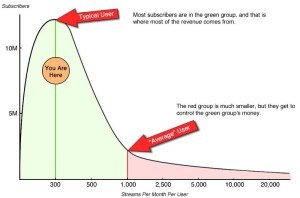

What started out as a similar business model (individual song and album downloads) has transitioned into music streaming, led by Spotify and Apple Music. Both services charge $9.99 per month for unlimited music consumption (for the purposes of this analysis, I’m not going to include Spotify’s ad-supported free listening tier). What’s interesting about these platforms is that their consumption incentives are not entirely aligned with with those of the labels and artists. Why is that? As I’ll show below, customers that pay for a monthly subscription but don’t listen to a large amount of music are immensely profitable for the music platforms, but almost worthless to labels and artists.

Current per song payout rates from platform to label are about $0.006. If we assume the same 70/30 revenue split that the download-to-own model is built on, we can assume that $3 of every subscription goes directly to the platform (overhead costs, platform investments, etc), with the remaining $7 being available to fund the amount of individual listening a user does. At the current payout rate, a user would need to stream 1,167 songs per month in order for their $7 to be fully distributed to labels and artists. Based on recent statistics from Nielsen, actual platform listening is considerably lower than this on average. Consumers average 24 hours of music listening per week, which if done entirely via a platform like Spotify would equate to about 1,152 songs per week, or about breakeven for Spotify. The reality, however, is that this listening is not entirely concentrated on one platform — it’s spread out across radio, YouTube, Soundcloud, blogs, etc. So if not all of the $7 is being distributed back to artists and labels, where does it go? It stays with the distribution platforms! The business model of these companies means they prefer users that pay for a subscription but don’t stream enough to make them an unprofitable user.

So how does this relate to network effects? It is in the best interests of these platforms to provide enough value for users to justify paying for a subscription. They do this through two methods: offering a paid subscription as an incentive to get rid of advertisements while listening (which are annoying), and by leveraging the platform-enhancing direct network effects. Spotify’s smartest move was to deeply integrate Facebook into the platform, making music listening a social experience. Allowing users to follow artists but also other users opened up an entire social interaction experience through playlist sharing, listening activity feeds, and more. Even though the music library can be considered static beyond a certain point, the more users are on Spotify, the more valuable it is for any individual user to be on that platform. High switching costs are now associated with moving to another platform, where the ability to share and experience music with others is reduced or eliminated.

This is also where Spotify’s free tier came into play. Provide the platform and the content for free, recouping some money through advertisements. But gain a massive user base first (75 million total, 20 million of which are paid), gaining enough traction to be able to convince artists and record labels that their content must be present on the platform, and at a rate that makes it profitable for the technology company (even though each free tier listener is unprofitable). With enough users and enough consumption, artists and labels will continue to make more and more money compared to the early post-Napster days. But what they don’t share is the increasing amount of money that they themselves are making on every user (on average). Why shouldn’t this excess money be distributed to the artists and labels instead? For more on this idea, check out this fascinating article on how streaming music is ripping people off: https://medium.com/cuepoint/streaming-music-is-ripping-you-off-61dc501e7f94 The outcome of this will likely be a change in how people pay for their streaming accounts: perhaps paying based on amount of consumption. Until that time, the current model will continue to dominate.

References:

https://news.spotify.com/us/2015/06/10/20-million-reasons-to-say-thanks/

Very interesting article. As an avid Spotify listener, I often wonder how I can pay so little for unlimited music. I love the platform and for only $10/month it’s a no brainer for me. However, with musicians such as Taylor Swift taking their music off the platform for too little pay, I wonder how many of musicians will follow suit. If that happens, there is little incentive for me to stay with Spotify since I don’t own any of the music anyway. I would find little issue immediately switching over to the next best thing.

Very insightful, thanks Jeff!

I love the “Mix of the Week” playlist that Spotify introduced recently curating a playlist based on the songs I listened to during the previous week. It is quite impressive to me how accurately it matches my taste. This recommendation engine is another example how direct network effects work for Spotify: the more user on the platform the better it can recommend new artists and tracks based on what other people with similar tastes listen to.