How Can the U.S. Military Win in the Digital Age?

Even the world's must powerful military must radically change to adapt to Digital Innovation and Transformation

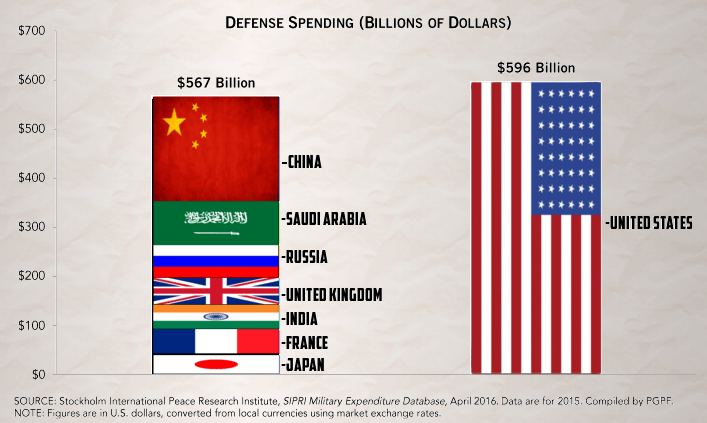

The United States military is certainly the most powerful in the world today. It’s clear in the numbers: the U.S. military has more than 2 million uniformed personnel and an additional 800 thousand civilian personnel; it operates 38 “named” overseas bases in dozens of countries around the world (China has one overseas base); and the U.S. spends more on defense than the next seven countries combined.

But the key question for the 21stcentury national security landscape is: can the U.S. military continue to lead in the era of the digital transformation of war? Like all the traditional industries we have seen in this course, the national security space is being disrupted by digital innovation. From manipulating information networks, to cyber intrusions in critical national infrastructure, to cyber-attacks (such as the Wannacry episode) which can severely daisrupt society, military professionals are increasingly focused on defending the civilian population from digital aggression. As such, cyberspace is increasingly viewed as the domain where future conflicts will take place. The U.S. military has taken note. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has recently made some major moves to adjust to the digital transformation of war.

In 2015, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter established the new Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx) in San Francisco to link DoD’s financial resources and defense priorities with Silicon Valley’s tech companies, expertise, and investors. DIUx’s expanding portfolio includes investments in AI, autonomous systems, and other emerging areas, as well as new offices in Boston and Austin to better connect with America’s competing tech centers.

Perhaps most importantly, late last year the Trump administration elevated U.S. Cyber Command (CYBERCOM) to be the U.S. military’s tenth “unified combatant command”. This is an important organizational change, as cyber used to be a subordinate command underneath U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM). The new CYBERCOM will be a joint organization, including personnel and financial resources from all five armed service branches (the Army, the Air Force, the Navy, the Marine Corps, and the Coast Guard). Elevating CYBERCOM reflected recognition of the growing centrality of cyber operations to national security and demonstrated the DoD’s commitment to cyberspace as a warfighting domain.

However, in my opinion, this change does not go far enough to ensure the U.S. military retains its competitive edge as the digital revolution progresses. Fundamentally, the elevation of CYBERCOM was just a sustaining innovation on the U.S. military’s current path. The most glaring indication of this is that CYBERCOM lacks an independent leader; Admiral Mike Rogers, the leader of the National Security Agency (NSA), is simultaneously “dual-hatted” as the commander of CYBERCOM. Rather than following the sustaining path, the DoD needs disruptive organizational innovation.

That is why I recommend the United States establish a new sixth branch of its Armed Forces: the Cyber Force.

The Cyber Force would be completely independent from the existing service branches. It would be staffed and resourced as a separate force. The benefits of a Cyber Force would be manifold for strengthening the American military’s digital prowess.

From an resource perspective, a separate Cyber Force branch could better advocate for dollars from the U.S. Government’s budget each year. CYBERCOM’s current budget is made up of contributions from the existing branches. Redundant spending by their overlapping structures wastes precious resources. A separate Cyber Force would more effectively negotiate for and more efficiently allocate budgetary resources to improve America’s digital defense posture.

The new identity of a Cyber Force would also be beneficial. An independent service branch would build its own brand identity, differentiated from the existing, well-rooted branding of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines. This unique brand-identity would help attract new people to join the military, especially younger, tech-savvy applicants who might not be attracted to the rugged, traditional identities associated with the elder service branches. A new digitally-identified force could also develop its own strategy and doctrine, rather than being diluted with legacy ideas from the services focused on land, sea, and air operations.

From an organizational culture perspective, the Cyber Force could be much more tolerant of risk-taking than the legacy branches. For example, a multi-hundred-million-dollar U.S. Navy ship with hundreds of personnel and thousands of explosive ammunitions on board can’t take many risks on the water. However, the nature of the Cyber domain allows for more testing of new ideas and techniques. “Failing fast” with hackathons would be more of the norm, not the more conservative “no man left behind” attitude necessary for physical military operations. This risk-tolerant culture is crucial for thriving in the first-paced world of digital innovation and transformation.

Finally, this change would radically improve the operational effectiveness of America’s cyber warriors. The legacy service branches are trained and organized to produce soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines who are ready for combat. They do this through a variety of instruments: tough physical fitness tests, rigorous hierarchy, competitive evaluations against their peers, and standardized uniforms for impersonal identities and traditional warfare. However, it doesn’t take a genius to recognize how these same mechanisms, while good for traditional military branches, are irrelevant or counterproductive for building a national cyber defense force. An autonomous Cyber Force could institute its own recruitment criteria, dress code, medical standards, and personnel evaluations. This would make it possible to attract, train, and retain the talent needed for the U.S military’s digital transformation.

Of course, there would be resistance that would need to be overcome for this to come about. To start, the U.S. military can’t do this on its own; it would require an act of Congress. While many questions at Mark Zuckerberg’s recent congressional testimony made clear some Senators don’t understand digital innovation, military leaders could work to build support for this change among younger Congressmen, perhaps from California or other areas whose constituents would stand to benefit from a new Cyber Force.

Additional resistance could come from the public itself, who might oppose the “militarization” of cyberspace. This would be best addressed though public diplomacy and educating the naysayers. Military leaders can demonstrate how this change would not affect the Posse Comitatus Act, which prohibits the federal government from using the military to enforce domestic policies. To go even further, military leaders should call for an equivalent civilian institution to govern civilian cyber affairs, much like the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates all civil aviation over the skies of America.

All in all, the national security space is changing quickly into a digitally-centric arena. The American military’s current domination of the air, land, and sea doesn’t necessarily translate into winning the digital-age of warfare. To better prepare for future conflicts, the DoD should move to set up an independent Cyber Force as soon as possible.

War of the Future…

Sources:

- https://www.defense.gov/About/

- https://www.acq.osd.mil/eie/downloads/bsi/base%20structure%20report%20fy15.pdf

- https://www.diux.mil/portfolio

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/pursuing-electronics-that-bend-pentagon-advances-partnership-with-tech-firms-1440756002?ns=prod/accounts-wsj&ns=prod/accounts-wsj&ns=prod/accounts-wsj

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/defense-secretary-revamps-pentagon-technology-unit-1463010360

- https://warontherocks.com/2017/08/getting-to-ground-truth-on-the-elevation-of-u-s-cyber-command/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-donald-j-trump-elevation-cyber-command/

- https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-01/time-us-cyber-force

- https://taskandpurpose.com/now-time-establish-standalone-cyber-force/

- http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-10_Issue-2/Yannakogeorgos.pdf

Thanks! What a interesting topic. As everything from information to decision-making process are moving online and heavily reliant on data and technology, I think having a dedicated Cyber Force is necessary to develop expertise on this front. From an organizational standpoint, I wonder what do you think about having a dedicated cyber force within each amy unit versu have one separate and independent cyber force. The former would have less frictions in sharing information and less likely to encounter strong resistance if it’s part of the unit itself.

Really interesting topic choice! I definitely agree that the senate/house would likely provide most of the resistance to any new groups created. It never ceases to amaze me how limited the understanding of technical topics is amongst our representatives. I question how seriously the public would fight any such initiative or if negative public sentiment would actually have any real impact (net neutrality serves as a recent example where public sentiment was outweighed by corporate lobbying money).

Another interesting digital trend the military will have to face is the use of artificial intelligence for data analysis. The military has access to tremendous amounts of data and, as computers become more powerful, will be able to use AI to detect patterns and even make action decisions. The role of intuition and human oversight is highly amplified for war-related decisions. Processes will need to be carefully designed to ensure algorithms are not blindly trusted especially when human lives are at stake.

This is by far the most insightful (and perhaps prenant) blog post i’ve read this whole year. Thank you for this, the reader can really tell you have genuine interest in the topic.

My 2 cents would be to look at how a similar experience has already been conducted (albeit on a smaller scale) in Israel.

The Unit 8200, as it is called, is composed at the soldier-level primarily of 18-21 year olds. Because of the youth of the soldiers, and the shortness of their service period (Israel has a compulsary military service of 3 years), the unit relies on selecting recruits with the ability for rapid adaptation and speedy learning. Finally, many former officers from this unit, end up in founding and/or running important tech companies in both the Middle East and Silicon Valley (…or at HBS). In turn, some of these companies keep feeding talent and business interaction into the military cyberforce.

While the US’ case is obviously different, perhaps would it be well-served to look into the 8200 unit experience when time comes to give inception to this dedicated cyberForce branch.

Interesting post, Austin! I agree that the military may not be adapting to tech changes as rapidly as it should be, but you are right, the creation of DIUx and the elevation fo CYBERCOM are good starts.

Some concerns about creating a new branch of the armed forces, although it is an interesting proposal. Resistance. As you pointed out, there will surely be resistance (I would imagine a lot!) from Congress, some from the public, and probably some from each independent branch. Although there may be an argument for saving resources by better allocating budgets or hindering redundant spending, I would imagine that the costs of creating the new branch would be incredibly expensive (building that brand). Most branches currently have a had enough time getting the funding they desire, so I could see arguments from those branches against allocation of funds toward a new branch entirely.

It may still remain difficult to attract young tech talent, even with a stand alone cyber branch. The US military simply cannot compete with the salary and benefits that traditional tech or private sector companies offer. The US military also loses talent to the private sector after the service members learn enough tech skills and gain enough experience to move on. This phenomenon isn’t unique to the military, it exists in the overall intelligence community (NSA, DIA, etc.).

It will be interesting to see how cyber (hopefully) evolves within the US military and militaries around the world.

https://defensesystems.com/articles/2018/03/19/cyber-pay-armed-forces.aspx

Great post. I see a lot of opportunities in partnerships with the private sector as well, or potentially something similar to a joint venture or even rotational programs. These would help bring fresh eyes and ideas in through potentially lower cost solutions than outsourcing huge chunks of the work.

This is my last comment and I would like to write it about ethics of technology. I believe it is extremely important if not the most in defense industry. The world discusses ethics of self-driving cars but we are facing the threat of robot armies sooner or later. It could be more disruptive than nuclear in reality. Hence, creating common values around how to use technology more ethically for the peace of the world in militaries is an existential necessity. US Army should lead the efforts and be a role model for the rest of the world.

Fascinating and important topic. I agree with many of the barriers already mentioned — particularly re: the difficulty of attracting talent (when their outside options are so good in terms of pay, and when in the private sector they are not bound to regular haircuts, a uniform, drug tests, travel reporting, etc.) An additional barrier, which Mike touched on, is the resistance that is likely to come from the traditional branches should the idea of a separate service be pushed forward — many of them see cyber as a big and growing pot of money over which they are unlikely to give up some claim unless forced (as evidenced by the proliferation of units with some element of “cyber” in their mission set).

I like the idea of looking to IDF 8200 for inspiration. It is a difficult model to copy while the US remains an all-volunteer force, but perhaps some elements of it could be a useful guide — particularly the on-the-job training, extensive/supportive alumni network, startup funding mechanisms, and first customer opportunities which IDF 8200 members get access to during/after their service. IDF 8200 deals with the issue of opportunity cost by reducing it (at least for folks with lower discount rates) — in return for a few years of service, your chances of hitting it big with a successful tech startup are significantly increased down the road (as evidenced by Israel’s “start-up nation” success).

Even if a “cyber force” is feasible, it is likely to take a long time to authorize/ standup. Hopefully cyber command can act as an innovative center for the military in the short term, drawing the best talent and sufficient dollars. The close connection with NSA may be an advantage, not a disadvantage, with respect to cyber command’s ability to attract resources and build credibility. Here’s to a successful digital transformation of the US military in a time of increasing great power tension/ competition!